Bookseller One Grand Books has asked celebrities to name the ten titles they’d take to a desert island, and they’ve shared the results with Vulture. Below is writer George Saunders’s list. His novel Lincoln in the Bardo was recently released by Random House.

If I were actually faced with the task of compiling ten books to take to permanent exile on a desert island (and by the way, how does one arrange that conundrum?), I would pick ten esoteric and difficult texts on Tibetan Buddhism and spend the rest of my life trying to understand and master those. Failing that, I would default to the usual suspects: the Bible, the complete works of Shakespeare, Chekhov, Austen, etc. More practically, I might want to choose books about how to build a boat, what is safe to eat on a desert island, or how to build a message-bearing drone out of coconut shells or something.

So, the list below is more like: Ten books that are helping me through the “current political moment,” i.e., this moment when our democracy stands on the brink of failure and our nation runs the risk of leaving its historical moment of greatness behind for something less and more mediocre, by becoming a materialist, corporation-dominated, frightened version of its best self.

Stamped From the Beginning: The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, by Ibram X. Kendi

This book should, in my view, be required reading for any white person in America who has felt that familiar combination of heartsickness and passivity when thinking about race. It is a valuable tool in the battle to wring all vestiges of racism out of oneself.

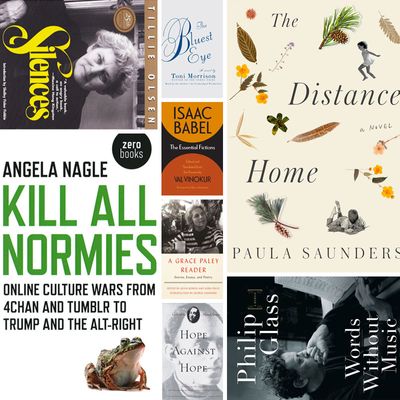

Kill All Normies: Online Culture Wars From 4Chan and Tumblr to Trump and the Alt-Right, by Angela Nagle

This book shot a lightning bolt of understanding into my mind regarding the role of social media in the terrible political division racking our country. It also made me think that we make a grave error when we mistake the virtual world (of anonymity, cowardice, surficial snark and posturing, one-dimensional, self-presentational bravado) for the real one — the one where people have to say things to one another’s faces, and are constrained, via the basic manners we are all pretty adept at learning, from being rude, dickish, or insulting.

Silences, by Tillie Olsen

Language is power, and Olsen does a masterful and compassionate job here of showing who has been denied language in America, and why, and by whom. Had speech really been free all of these years, we would have a different written history: more female, more working class, more immigrant, more of color. And the result would be truer.

The Distance Home, by Paula Saunders

Okay, yes, this novel is by my wife. Denied by marriage the chance to enthusiastically blurb this book, as I would do in a heartbeat had a stranger written it, I feel I’d be remiss if I didn’t take this chance to say here that this story, and the author’s heartful understanding of it, has been deeply informing my views on class and addiction in America for 30 years. And that her masterful writing of it here represents an original and essential part of the American story — and especially the way family functions, or doesn’t — that I have never seen represented before. I don’t know a book that better describes the way that, as Terry Eagleton put it, “capitalism plunders the sensuality of the body.” A loving family tries to make a positive home for its children and is derailed in this by our American propensity to strive and be violent. There is something remarkable and new going on here in the way point of view works, that models a true “God’s eye” view: everyone right, everyone wrong, everyone valid.

The Essential Fictions, by Isaac Babel (new translations by Val Vinokur)

I turn to Babel for reassurance that literature is capable of showing the real and terrifying mayhem that results when national systems collapse, while still preserving some modicum of love for human beings. If I ever need my ear tuned, this is where I go. Babel is a particular master of that unnamed space between sentences; the place where, in my view, a piece’s real sensibility gets made: What does the writer omit, and how does he link his observations? A reader might profitably link a reading of Babel with the author’s 1920 Diary (which record the actual events on which his legendary collection Red Cavalry were based) and with a remarkable forthcoming book of stories, Bring Out the Dog, by Will Mackin, which brings a Babelian level of specificity and style to our recent American wars.)

The Bluest Eye, by Toni Morrison

The first time I read this book it transported me back to my early Catholic days on the South Side of Chicago, when the nuns put forth a model of Christ as a kind of superhero, whose superpower was love, defined as his ability to look with affection at anyone and everyone, no exceptions. Morrison models that capability here in this great novel, and reminds us that the first move in any assessment of a person or notion should be sympathy, based on the reality of our grand mutual suffering.

Words Without Music: A Memoir, by Philip Glass

Read this memoir for a glimpse of a vanished country (ours, circa 1940s/1950s/1960s) that had an entirely different notion of education and the arts, i.e., a country that valued them and honored them and supported them with money and muscular institutions, which institutions, in turn, produced courageous and original national artists like Glass — who is also, turns out, a wonderfully gifted, honest, and amiable writer.

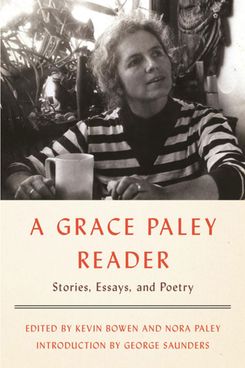

A Grace Paley Reader: Stories, Essays, and Poetry, by Grace Paley

If anyone ever asks if an artist should be primarily concerned with aesthetics or politics, answer with three words: “Yep” and “Grace Paley.” Her funny, fond, wild energy produced stunningly beautiful stories, poems, and essays, and a lifetime of passionate social engagement. Pair this with the lovely documentary (Grace Paley: Collected Shorts) by Lilly Rivlin, for a sense of who Grace Paley was, and why it’s so important to keep her memory and work alive in our time.

Dispatches, by Michael Herr

Herr, who recently passed away, was one of the great prose stylists of the 20th century. Reading Herr (whether in this book, the best thing written about Vietnam, or in Kubrick, his short, vivid defense/explication of Eyes Wide Shut) is immensely instructive and hopeful; he always makes me feel that, yes, the English language can be used to interrogate any dilemma, no matter how complex. Herr’s rich, high-culture/pop-culture language and his stunning level of erudition allow him to put all doubts and counterarguments into play and create a sturdy mosaic of ambiguity, with an affectionate but skeptical mind at the center of it. I wish he was still with us and writing about this moment — there’s no one I would trust more.

Hope Against Hope, by Nadezhda Mandelstam

It seems to me that one thing we should be trying to keep in mind these days is the phrase, “It could be worse.” This book shows us a much worse time and its tragic effects on a group of tender friends/lovers/artists. We should energetically protect our system, and try to heal the toxic divisiveness afflicting us, and resist the lies being routinely promulgated, from above and on social media, because when a system fails, the victim is human decency — all these dear hearts suddenly living reduced, fearful, degrading lives. We have, as Paul Simon put it, “lived so well, so long” that we may be in danger of forgetting that the results of chaos are real. Mandelstam helps us see this, in beautiful, human-scaled, and terrifying detail. (Another book worth reading in this spirit: I Will Bear Witness, Volume 1: A Diary of the Nazi Years, 1933–1941, by Victor Klemperer.)