Light spoilers for Isle of Dogs below.

Wes Anderson loves movies, and he doesn’t care who knows it. His detractors might counter that nothing is more important to the director than people knowing this, that he flaunts his references as cool-kid posturing to earn style points. His fans far outnumber the opponents, however, and they adore the way Anderson weaves together disparate influences to create something entirely new, like a clean and polite Quentin Tarantino. Modern cinema’s premier symmetry fetishist has gained such a sizable and devoted following in part because his savvier fans enjoy matching wits with a director who shares their encyclopedic obsessions. And those not already in the know get turned on to a whole backlog of hidden classics with every new release; a novice viewer notices a cool-looking shot, does a bit of light Googling, and next thing they know, they’re knee-deep in the oeuvre of Jean-Pierre Melville.

Anderson hasn’t minced words about the inspiration for his latest effort Isle of Dogs, a stop-motion fantasy set in a futuristic Japan where a canine epidemic has gotten all pooches exiled to an island made of garbage. During the press conference following the film’s world premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival in February, Anderson name-checked two pop-cultural precedents. The first was the Rankin-Bass stop-motion specials, the herky-jerky holiday gems featuring your old pals Santa, Rudolph, and the Miser Brothers. The other was Akira Kurosawa, the single greatest filmmaker that Asia has ever produced. (Sorry, Ozu fans, but the truth hurts sometimes.)

Anderson remained mum back in Berlin when questioned as to how, exactly, Kurosawa’s work figures into Isle of Dogs. But even on the first watch, a viewer is smacked right in the face with a panoramic visual grandeur that could only belong to the painterly master of yore — just rendered on an itsy-bitsy scale. Some of the references are more Easter egg-ish and some have been integrated into the general fabric of the film, but either way, Kurosawa’s all over the place. For the benefit of the casual viewing public, Vulture has made five selections from his extensive filmography that most closely inform Isle of Dogs, as a pre- or post-viewing companion to this worthy homage. Now strike up the taiko drums and read on:

Stray Dog

The title of Kurosawa’s seminal cop drama is metaphorical in nature: A pickpocket ganks a service pistol from fresh-faced homicide detective Murakami (Toshiro Mifune, in the third of 16 films he’d lead for Kurosawa), who must then venture into the Tokyo criminal underground to retrieve it and salvage what’s left of his honor. Murakami is as much of a stray as his wayward gun, placeless in a Japan still piecing itself together following the devastation of World War II. His winding trail through the firearms black market acquaints him with other “strays,” orphans and veterans, people left behind by a society that simply lacks the resources or emotional bandwidth to care for every last person.

The concept of the stray factors prominently into Isle of Dogs, and not just because the plot revolves around the search for the missing hound, Spots. The characters divide themselves along the distinction of house pet versus street dog, the former typified as civilized and the latter as savage, an easy stand-in for prejudices along racial or class-based lines. Moreover, Spots’s owner Atari is something of a stray himself, having lost both of his parents in a bullet-train crash at a young age. Atari shares an alienated disconnect from the world around him not only with pretty much everyone peopling Wes Anderson’s handcrafted universe, but also the isolated heroes drifting through Kurosawa’s films.

Seven Samurai

We can and should debate ad infinitum over what Kurosawa’s crowning achievement might be, but the argument is most easily made for his heaven-scraping samurai epic. The story of a roving warrior leading a band of swordsmen to protect a helpless village from bandits fits into a long onscreen narrative tradition starting with John Ford and trickling down to A Bug’s Life. While Anderson didn’t nick the plot’s schematic, he did sample liberally from the master’s magnum opus. Though Alexandre Desplat composed the frenetic score and the soundtrack includes an expertly selected needle-drop from the West Coast Pop Art Experimental Band, what really sticks out are a pair of cues transplanted directly from Kurosawa’s work. The first comes from the early Kurosawa-Mifune collaboration Drunken Angel, and the second has been taken right from Seven Samurai.

An early scene in Isle of Dogs pits our heroes (a motley gang of alpha woofers voiced by Bryan Cranston, Bill Murray, Jeff Goldblum, Edward Norton, and Bob Balaban) against a rival pack for the spoils of a sealed trash bag. The showdown between the two dog squads goes shot for shot with a similar sequence in Seven Samurai, alternating rhythmically between wide shots of the assembled combatants and tighter close-ups on each of their faces as they steel themselves for battle. Wes Anderson fans, true to obsessive form, have already assembled some frame-against-frame comparisons using footage from the trailer.

Throne of Blood

A longtime student of dramaturgy, Kurosawa reimagined Macbeth from an onstage Scotland to an onscreen feudal Japan using noh techniques for one of his most violent tragedies. As the title suggests, general Washizu (Mifune, back again) leaves a trail of carnage behind him as he claws a path to the top of the military heap, his nefarious wife Asaji (Isuzu Yamada) egging him on every step of the way. This one stands out in Kurosawa’s filmography by virtue of a particularly adventurous visual sensibility, swathing many of the key scenes in dense, forbidding, mysterious fog.

The color white gets put through its paces in Isle of Dogs, clashing with the light silver of Atari’s suit and the various darker grays of the trash island to resemble something like a monochrome movie. Like Kurosawa before him, Anderson uses fog to great effect here, with wisps of cotton or some other fuzz flooding the frames with white. Working in stop-motion allows Anderson an evocative sense of tactility that suits the sensuousness of the fog perfectly.

High and Low

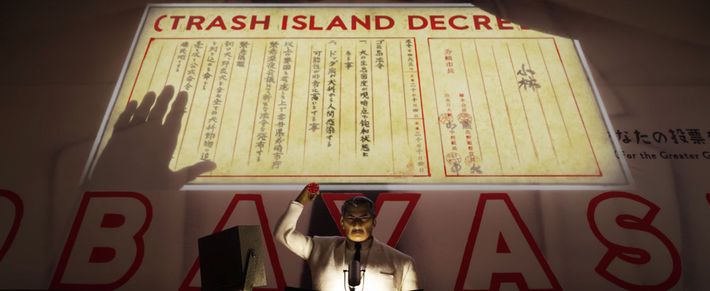

The villain of Isle of Dogs is the tyrannical Mayor Kobayashi, the scion of an age-old cat-loving dynasty hell-bent on the destruction of all dogs. He resorts to all manner of underhanded tactics to ensure the extermination of man’s best friend in the fictitious Japanese metropolis of Megasaki, from discrediting his political opponents to deceiving the public. (It is, in many ways, a timely film.) In the ornate Municipal Dome, Kobayashi glowers down over all his underlings from a stories-tall tapestry, square-jawed and eternally frowning.

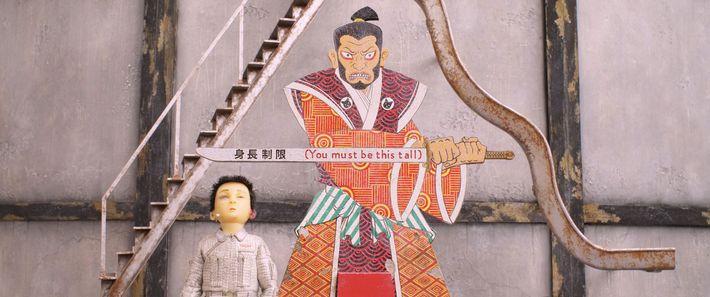

Less in methods and more in overall look, Mayor Kobayashi harkens back to Kingo Gondo, the mustachioed executive that Mifune portrayed in Kurosawa’s 1963 corporate thriller. Just as Kobayashi jockeys for control of the city and contends with dissent from within via the supremely creepy Major-Domo, so too does Kingo wrestle with opposing factions within the shoe company he oversees. But the slicked-back hair, the immaculate white suits, and the upper-lip caterpillar all peg the two characters as distant relatives.

Ran

Kurosawa returned to Shakespeare once again in the high point of his late-career phase, using King Lear as a jumping-off point for a period piece about an aging warlord divvying up his kingdom among his three sons. Each of the heirs — Taro, Jiro, and Saburo — has their own small fiefdom, and Kurosawa capitalized on his transition to color film by clearly coding each of the sons with red, blue, or yellow.

Anderson’s a fan of monochromatic color-coding himself, having most recently indulged that whim with the clandestine Society of the Crossed Keys in The Grand Budapest Hotel. When Anderson gets off the floating mass of refuse and returns to the bustle of Megasaki, he mimics Kurosawa’s use of color, choosing one hue to guide the design of each tableau. Anderson is all about creating and maintaining compositional order in his little world, and that extends to the coloration. Every handpicked prop, every shade of red, all in their right place.