The annals of screen entertainment are littered with accessories in denial. “Chapter Five: Do Your Job” places Barry in a narrative lineage stretching from Rick Blaine all the way to Baby the driver, men adjacent to reprehensible behavior who can nonetheless convince themselves of their own innocence. They’re masters of rationalization, establishing a code or sticking to a principle that exonerates them from culpability in their own mind.

But Barry’s guiding tenet of only killing those who deserve it has been tested a lot as of late, and disposing of Ryan Madison (whose only crime was sleeping with the wrong woman at the wrong time) set off a series of ethical trials that threaten to shatter the standard completely. All of these men eventually reach a point when they can no longer pretend that they’re guiltless of the crimes they helped facilitate. It was Nucky Thompson, Steve Buscemi’s Boardwalk Empire politician turned crime lord in spite of himself, who received the advice that you can’t be half a gangster. And he never had to handle a sniper rifle.

After a slow build of episodes gradually confronting Barry with the ramifications of his actions, “Do Your Job” finally breaks him. Violence can be an ethically thorny thing, as laid out in a heated classroom discussion regarding the internal profiles of Macbeth and his Lady. Barry immediately identifies with the passive, easily swayed Macbeth, and defends the both of them with the unconvincing albeit fair suggestion that not everyone who kills is some kind of psychopath. Macbeth is just following orders — that old constant refrain of soldiers, a group that includes both Barry and Nazis. His classmates argue that Macbeth controls his own fate, and that as the executor of the act, he may be more stained than the Lady who planned it. They’re both right, which is what makes Macbeth such a great work of dramaturgy, though Barry maintains that “Shakespeare whiffed it on this one.”

As has become the order of the week, an uncomfortable classroom hypothetical follows Barry into the real world, where he must weigh his ideals against the difficult demands of his high-stakes life. The “irredeemable fuckin’ psychopath” warned of during class appears to Barry in the hulking form of Taylor, the unsettling ex-Marine who muscled his way into Barry’s operation at the close of last week’s installment. He won’t stop leaving Barry menacing and weirdly plain-spoken voicemails — “Barry, Taylor. Hope you haven’t killed the Bolivians yet. I really want to kill those guys. Fuck yeah.” – and in him, Barry recognizes a warped version of himself devoid of any remaining moral fiber.

In the warehouse shootout nimbly captured by episode director Hiro Murai (for my money, the most exciting TV helmer currently working), Barry witnesses the savagery that would ensue if he let go of his humanity. Taylor’s got a serious fetish for violence, describing the prospect of murdering two dozen men as “a party” and running into a firefight with the gleeful battle cry of “LEEEEEEEEROY JENKINS!” Barry doesn’t want to turn into a bloodthirsty freak like him, and the thought that passivity might be all it would take to get there chills him to the bone. So when all the Bolivians have been slain and Barry’s got the muzzle of his gun against the back of Taylor’s head, the terms of his choice are clear. He can maintain his regimented lifestyle and sink deeper into turpitude, or he can invite chaos into his life in exchange for a shot at redemption.

Barry makes the right choice even though it spells near-certain doom for him, an encouraging step toward the light. It really sticks when Sally tells him, “I feel like you’ve got some toxic masculinity issues to work out,” though his issue is really more that he’s bad at taking social cues, never mind that every passing week reveals Sally to be a slightly worse person. Even after watching her give less-than-constructive criticism to a classmate out of spite over casting, he still holds her opinion of him in high esteem, and so Barry edges away from the most toxic and masculine parts of himself. He might have a misunderstanding of the concept, but the general directive to live more mindfully and gently connects with him. He wants to be a good person more than he wants to be a good hitman, two pursuits that are beginning to look diametrically opposed for Barry.

If letting Taylor live costs Barry his life, he’ll know that retaining his core empathy will have been worth it. That’s what he’s telling himself, at least, but as he points out during the classroom Macbeth debate, it’s a lot easier to deal in the theoretical. Mercy seems like a nice quality until it lands you in the crosshairs. While exercising agency makes you a richer character in your own life, full-fledged characters get defined by the conflicts they overcome. Up to this point, Barry has let other people pull his strings, and he’s bound to soon remember why he spent so much time letting things happen instead of making them happen. To live means putting your life on the line, in performance as in love as in contract assassination. One look at Ilsa Lund, and Rick Blaine grew a conscience; it’s taken Barry a little longer and a much higher body count, but he’s gotten there too.

Bullet Points

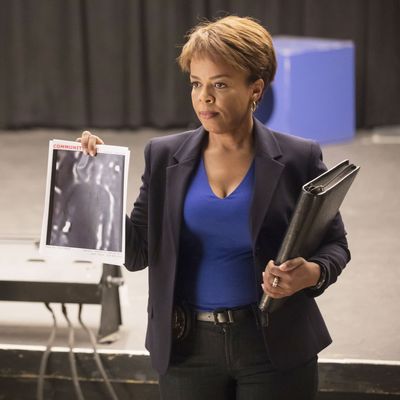

• As someone who has spent the last decade and change on a personal crusade to rid all scripts of the “zoom and enhance” scourge, I sympathized deeply with Detective Moss’s exasperated “that’s not a thing” in response to one student’s advice based on his crime procedural gig.

• Henry Winkler continues to lay waste to every line of dialogue thrown his way, inciting hysterics with his straight-faced read of “Be on the lookout for a man with no discernible features. He killed your friend.”

• Noho Hank’s evident delight at the new frontiers of text messaging continues, as he has apparently discovered the adorable, deeply off-putting magic of Bitmojis. He’s also a big fan of the children’s gymnastics facility where Goran’s daughter takes classes. They’ve got trampolines and everything!

• Barry can’t stop picturing his cozy Leave It to Beaver-styled dream life with Sally, moving this week from his cookout with best pal Jon Hamm to the family-man era, where he can project his feelings of weakness and vulnerability onto his imaginary son Denzel.