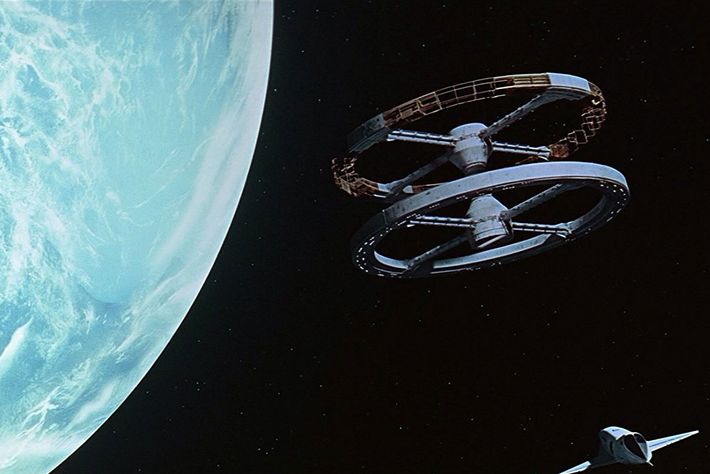

In 1964, fresh off the heels of his Cold War satire Dr. Strangelove, director Stanley Kubrick decided that he wanted to make a film about “Man’s relationship to the universe.” He teamed up with acclaimed science-fiction writer Arthur C. Clarke to develop a novel and screenplay in tandem inspired by Clarke’s short story “The Sentinel,” about the discovery of a mysterious artifact on the Moon left behind by ancient aliens. The two men were determined to avoid fantastic, exaggerated depictions of space, instead emphasizing realism and scientific accuracy to properly buttress their ideas. After they spent two years on the novel and script, Kubrick embarked on a two-year production process that went over budget and behind schedule, largely due to his perfectionist tendencies (he was making crucial cuts just days before his film’s general release). In April 1968, 2001: A Space Odyssey had its world premiere in Washington, D.C.

Upon general release, critical reaction was mixed, with most praising the effects but criticizing the film’s pacing and steely tone (Pauline Kael and Andrew Sarris, who were “rival” critics at the time, both hated the film, while a young, green Roger Ebert championed it). Yet, 2001 had a noticeable impact on the culture, garnering acclaim from counterculture audiences who responded to the film’s visual style and philosophical implications, as well as a new generation of budding film directors — Spielberg, Lucas, Scott (Ridley) — who were mesmerized by Kubrick’s vision. By the end of the 20th century, 2001 was rereleased into theaters three separate times, and now, 50 years later, it’s considered Kubrick’s magnum opus and a pioneering work of film art.

2001 casts an enormous shadow on the last half-century of pop culture, let alone the science-fiction genre. Of course, the film’s core story has become a touchstone — a sentient computer turns on his human counterparts when their shared mission becomes jeopardized — but more than that, Kubrick’s consciousness-oriented presentation of complex, multi-interpretive ideas has lingered in the culture for decades. Clarke opted for a clarifying, expository approach in the novel, befitting his literary background, but Kubrick wanted to reach audiences on a primordial level, eschewing traditional narrative convention to do so.

If you’ve ever pondered why so many moments in 2001 are iconic — Dawn of Man; the Monolith; the bone-satellite match cut; the Lunar landing scored to “The Blue Danube”; “Open the pod bay doors, HAL.” “I’m sorry, Dave. I’m afraid I can’t do that.”; HAL singing “Daisy Bell” as he dies; the psychedelic Star Gate sequence; the Star Child floating above the Earth, gazing at the planet below — it’s because they’re designed to inspire wonder and contemplation, rather than a simple explanation. The film perfectly embodies the spirit of space exploration, complete with the awe and terror of potentially discovering that we’re not alone.

We’ve decided to catalogue the ways 2001 has influenced science fiction and pop culture, and how so many artists have kept its legacy alive with tips of the hat, pointed tributes, or spiritual connections. Its origin and purpose might no longer be a total mystery, but it has nevertheless captivated audiences and creators alike with the promise of something bigger and grander than our wildest imaginations.

Philosophical & Poetic Science-Fiction Films

With 2001, Kubrick not only opened up a market for commercial science-fiction blockbusters — Star Wars, Close Encounters, Alien, etc. — but also for cerebral sci-fi that tackled existential questions about humanity’s relationship with technology and an unknowable universe. The 1970s offered a treasure trove of philosophically provocative films steeped in abstract ambiguity, some of which include Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris (which was seen by many as a response to Kubrick’s film); Nicolas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth; Saul Bass’s Phase IV; René Laloux’s Fantastic Planet; and Silent Running, the directorial debut by 2001 special-effects supervisor Douglas Trumbull. Producers eventually turned on such heady sci-fi properties in the 1980s, spurred by the box-office failures of films like Dune and Clarke’s 2001 sequel, 2010, but they soon made a comeback with the emergence of the internet and the rapid development of high-quality special effects.

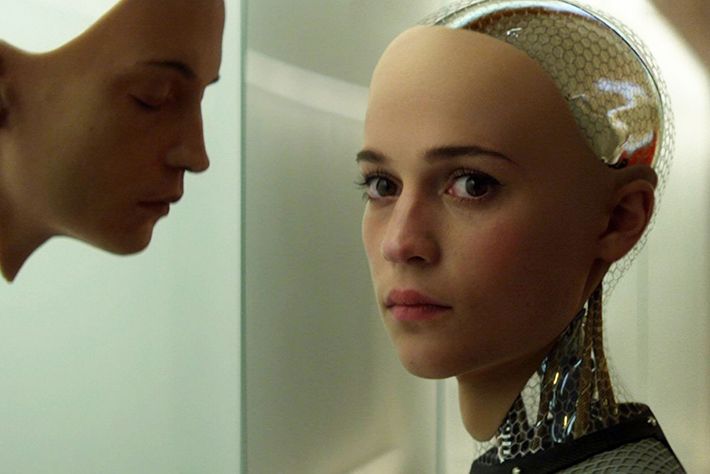

The 21st century has seen a host of acclaimed science fiction that run the gamut between big studio and independent productions, many of which follow Kubrick’s philosophical rigor. Films like Alfonso Cuarón’s Gravity, Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, and Denis Villeneuve’s Arrival sensitively tackle ideas of space travel and artificial intelligence with Kubrickian scale, submerging viewers in enormous otherworldly atmospheres. Other, smaller scale productions like Shane Carruth’s Upstream Color, Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin, and Alex Garland’s Ex Machina are more interested in examining difficult existential questions than technological immersion. The recent critical and cult success of Annihilation indicates that potent, imaginative sci-fi still has a place in our ever-changing cinematic landscape.

Production Design & Visual/Special Effects

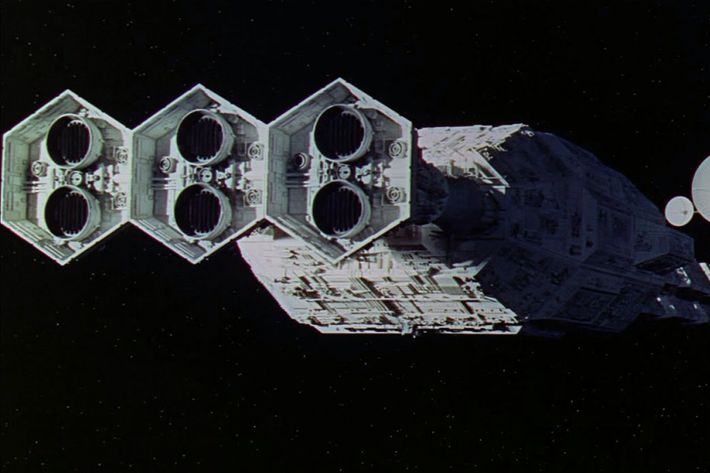

2001’s effects team, led by Douglas Trumbull, was notable for its use of in-camera techniques and pioneering front projection for extensive backgrounds. Intricate models of spacecraft were carefully photographed for a realistic depth of field, while interior shots of the ship were created by enormous sets, such as the rotating centrifuge. These majestic effects, many of which were influenced by silent-era practices, were employed to create a sense of realism that was otherwise absent from the sci-fi films of the era. (Little did Kubrick and his team know that NASA would land a man on the Moon the very next year, providing a real-life referent for future films.)

The sheer scale and craft in 2001 was used as a model for future production/effects teams to create their own sci-fi worlds. In fact, Peter Suschitzky, cinematographer on The Empire Strikes Back and Mars Attacks!, argues that 2001 led to a VFX arms race. Trumbull’s assistant John Dykstra co-founded Industrial Light & Magic and led the special effects on Star Wars. Trumbull himself created the effects used in Spielberg’s Close Encounters and introduced the use of lens flare to make the shape of a flying saucer. With the innovation of CGI, many films no longer have to rely on literal models to create new and exciting worlds, but Kubrick’s expansive vision has influenced many working in new technological fields. Visual-effects supervisor John Gaeta invented the Bullet Time effect for The Matrix partially because Lana and Lilly Wachowski allowed him to explore new forms. “[2001] led to startling breakthroughs and a level of immersion we haven’t seen before,” he said. “[The Wachowskis] acted very much for me like Kubrick acted with [Trumbull].”

Music

Kubrick famously used existing classical-music compositions as leitmotifs for 2001, most notably Richard Strauss’s “Also Sprach Zarathustra” and Johann Strauss II’s “The Blue Danube.” Both pieces experienced an immediate resurgence in popularity following the film’s release and are now inextricably tied to Kubrick’s visual palette. Directors such as Mike Nichols and John Cassavetes tipped their hat to 2001’s soundtrack in Catch-22 and Minnie and Moskowitz, respectively, no more than a few years after Kubrick’s film. Now one needs to look no further than a Simpsons episode to find homages to 2001’s use of music.

Kubrick’s soundtrack for 2001 was instantly iconic in a way that can’t be reproduced, and subsequent sci-fi classics have employed memorable film scores to convey the majesty of space travel rather than existing recordings. However, the film’s music helped pave the way for more unconventional music cues in science fiction, such as the use of pop songs to convey collaboration or peace, e.g. David Bowie’s “Starman” in The Martian. Plus, it’s not difficult to make a leap between “The Blue Danube” and, say, Daft Punk’s electro-orchestral score for Tron: Legacy in terms of conveying awe.

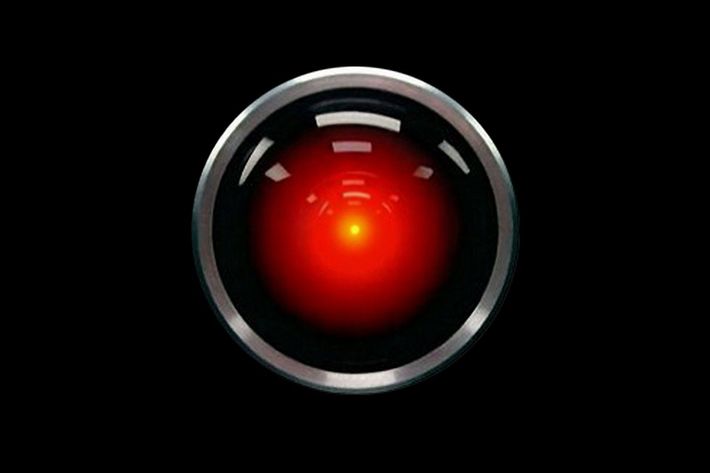

HAL

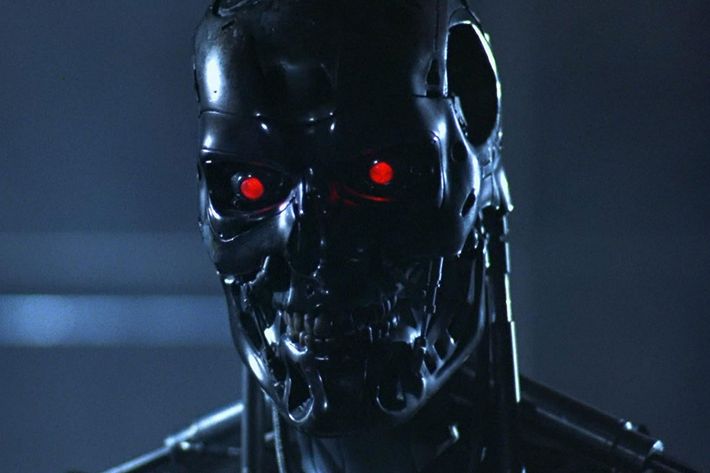

HAL 9000, the sentient computer at the heart of 2001, voiced by Douglas Rain and depicted as a camera lens, stands as the most memorable “character” from the film, paradoxically for his human characteristics. Faced with the prospect of disconnection after an internal malfunction, HAL eventually turns on the Discovery One astronaut crew, killing Dr. Frank Poole (Gary Lockwood), before being manually shut down by Dr. David Bowman (Keir Dullea). HAL represents a common fear of artificial intelligence, in that man-made technology will eventually turn on its creators after gaining enough knowledge and consciousness.

Modern science fiction has no shortage of examples of AI that either threaten humanity’s livelihood or open it up to new experiences. Michael Crichton’s Westworld explored the idea of AI programmed to fulfill human desires, only to develop ambitions of their own. Ridley Scott’s Alien imported HAL into the Mother system on the Nostromo, as well as having Ash (Ian Holm), the ship’s science officer, later revealed to be an android himself. James Cameron’s Terminator postulates a world in which an AI system, Skynet, gains self-awareness and takes over the world. Meanwhile, other films like Steven Spielberg’s A.I.: Artificial Intelligence and Spike Jonze’s Her imagine worlds that feature computer systems with distinctly human features, blurring the line between flesh and hardware. It’s a different world than the one Kubrick inhabited, but we’re still trying to sort out how technology can assist us, love us, or destroy us with just a change in circuitry.