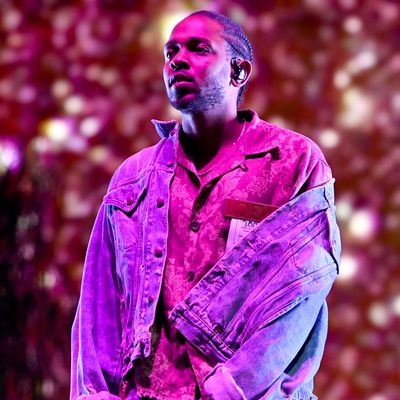

Kendrick Lamar has always had a thing for titles — why else, on repeated occasions, would he crown himself King? The Compton rapper has a natural understanding of the weight of formal recognition. With every fresh honor comes a new duty, something more to live up to. Last year’s DAMN. cast the artist’s character in an uncertain light: With his royalty now generally acknowledged, Kendrick dug into the latent fissures in the throne, examining how contingent and strange the phenomenon of “Kendrick Lamar” had always been. It’s most clearly expressed on the album closer “DUCKWORTH,” but DAMN. as a whole is pervaded by the sentiment that it would only have taken a single wrong turn for Kendrick to have become an anonymous body instead of a world-bestriding musical titan. All crowns are heavy in his world, and all who wear them must bear a corresponding increase in pressure, and in responsibility.

In the grand scheme of things, DAMN. being awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music is not an especially onerous honor. Few people, if any, rely on the Pulitzer to stay current with music. Throughout its history, the award, granted by a rather narrow circle of jurors, has been effectively reserved for white composers of classical music, with the occasional black jazz artist (or, more recently, Chinese composer) thrown in for good measure. Classical music, and contemporary classical music especially, registering not at all in a landscape of American music determined by pop sensibilities filtered through recording conglomerates, the music Pulitzer was an obscure bauble coveted only by the people who cared about it, of which there were not many. Forget the big reporting and magazine awards; even the poetry Pulitzer mattered more than music. Grammys are the awards that count most in music, and given that Kendrick is already loaded with golden gramophones — though the Album of the Year continues, unconscionably, to elude him — the Pulitzer is just a feather in his Dodgers fitted cap.

Sure, the Pulitzer connotes prestige and carries overtones of High Art, but anyone paying attention to Kendrick would already know to take his albums at least as seriously as one would take an experimental orchestra concerto. Most awards feel like a favor granted to the recipient, but in this case it’s Kendrick himself who’s doing the award a favor. Thanks to him, the Pulitzer Prize for Music feels relevant for the first time in recent recollection. We can only hope that more Pulitzers end up in the hands of popular artists. Metro Boomin would look nice at the Pulitzer ceremony; Beyoncé would be stunning wearing a gold Pulitzer medal. But it’s clear that Kendrick’s winning the Pulitzer is meaningful precisely because he doesn’t need it. He didn’t come to the award so much as the award came to him, and if it hangs around his neck easily, it’s only because he’s long been accustomed to more strenuous burdens.