In a diner nestled somewhere in Portsmouth, a town in the Pacific Northwest, Detective Rowan Black walks into a trap. A bespectacled mad man forces her to step into a pool of gasoline as he holds a lighter over it. But a simple incantation from Rowan deflects the flame, consuming her unnamed captor, who dies writhing in agony. It’s here the painterly grayscale comic blooms into color. Rowan’s eyes light up with shades of auburn and blue. The flame that swallows the criminal is brilliant shades of red and crisp yellow. It would be beautiful if it weren’t so gruesome. The introduction of color signals how momentous this event is — it’s this death that kicks off the narrative of writer Greg Rucka and artist Nicola Scott’s occult neo-noir Black Magick, whose second volume is out this week from Image Comics.

Since the fiery cataclysm in its first issue, Black Magick has unfurled all manner of pleasures and frights as it charts Rowan’s quest to find out who or what is targeting her: carefully plotted spells, demons in the form of little girls with their lips sewn shut, a talking black cat named Hawthorne who operates as Rowan’s familiar. In dealing with a sect of witch hunters responsible for the deaths of those in her family line and demons whose motives remain unclear, Rowan is aided by fellow witch and good friend Alex Gray. Meanwhile, keeping the secret of being a witch, even as it weighs on her work, causes her once-intense bond with her detective partner Morgan to falter.

There are several highly different, utterly gorgeous witchy comics out currently, including the ornate and brutal fantasy epic Monstress and the Florida-swampland-based horror Redlands. All three are by Image Comics and explore the ways the lives of women have been circumscribed by forces larger than themselves. Lately, I have been especially intrigued by the way Black Magick approaches the ideas of destiny and free will, the weight of familial inheritance, and the narratives we create for ourselves through Rowan, one of the most complex new characters I’ve had the pleasure of reading in comics within the last few years. Collaborators Rucka and Scott have delicately married the grit of neo-noir and brilliance of occult-driven horror, the terrifying with the enchantingly moving, concerns about the thorny nature of human psychology with a curiosity about the otherworldly.

What’s immediately impactful, even from the first page of its earliest issue, is the gorgeous art by Scott, a longtime friend of Rucka’s who worked with him most recently on the bright and hopeful Wonder Woman: Year One run at DC Comics that concluded last year. She clearly has a shorthand with her fellow collaborator. She works predominantly in a delicate black and white, placing it within the noir context the narrative partly hews toward. Her shadows aren’t sharp but soft, hazy, alluring. The occasional intrusions of color — when Rowan goes through an important rite at 13, when she faces the demons that have been pulling the strings of her life — are gently woven into the landscape of the story to cue us into big moments about the magic that guides Rowan’s life. Scott is amazing at filling her frames with small details that work together to speak to the interior lives of characters — the family memorabilia that occupies Rowan’s home, the specific clutter of the police station. In an interview with the Witch Wave podcast, Scott noted how much she pulled from her own childhood to create the design and interior accoutrements of Rowan’s home. It’s this level of loving detail that makes the art of Black Magick stand out in the comic landscape. The design of the demons — particularly one that reads as a touch indebted to David Bowie’s Thin White Duke era — is equal parts entrancing and terrifying because it lives where I feel the best horror can be found: two steps away from reality. But the greatest strength of Black Magick’s visual world is its female gaze.

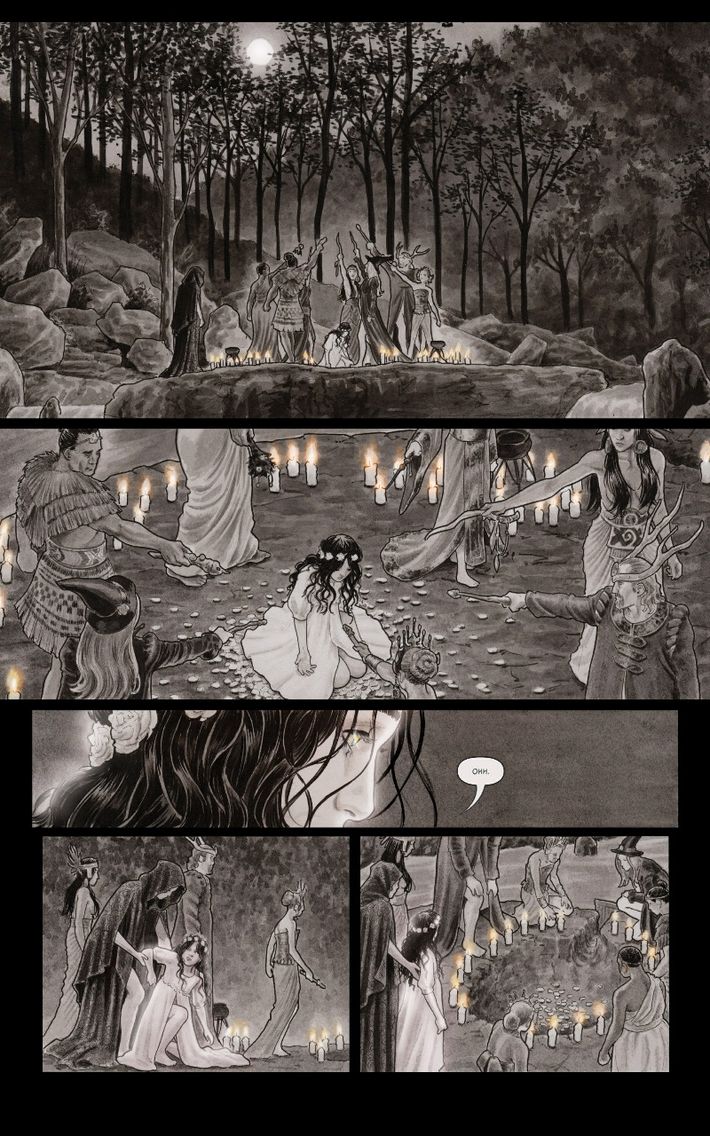

There’s no single vision of the female gaze in pop culture. In Black Magick, it can be seen in the diverse renderings of bodies, the lack of exploitative sleaze when female characters undress (which is rare and happens usually as part of witchcraft rituals), and the way Rowan’s partner, Morgan, is drawn as a pure, delicious beefcake. What makes the comic so dazzling is how the world-building and art come together, adding dimensions to the woman at the center of the tale. World-building isn’t merely about more fantastical elements and complex renderings of witchcraft rites, but about how the nature of setting informs a character’s psychology.

I’ve long been drawn to characters like Rowan, women defined by their blend of steely determination and hidden vulnerabilities. Yet the sixth issue, which kicks off the second arc, proved to be a turning point. Up until then, I found Rowan to be a fascinating character, but not one who fully resonated with me on an emotional level even though I found myself somewhat moved by the intensity of her bonds with the people in her life. But issue six offers a peek into Rowan’s past, exploring her 13th birthday and the rite that acts as her entry into adulthood, and her true awakening as a witch. Teenage Rowan is nervous as she speaks in front of the elder witches who will be a part of that ceremony. Her small form seems dominated by the lushness of the forest setting with a full moon glowing above her. The ritual is a mostly quiet affair as Rucka offers minimal dialogue, instead focusing on the specificity and texture of this ritual. Once submerged in the waters in the stone clearing, Rowan truly embraces her lineage. But her awe gives way to fear when she inherits the memories of her predecessors. For Rowan, the idea of witches being burned at the stake isn’t merely familial lore, but a memory from another life that can be recalled in all its painful sensory detail, from the stench of burning flesh to the horror of those final moments. In the months following the rite, Rucka depicts Rowan falling apart. She’s plagued by nightmares and starts fights at school. This spans two pages in thin panels that show only slivers of turmoil, but the way Scott tenderly evokes Rowan’s grimace and tears, the pain becomes distinctly felt.

I’ve been thinking a lot about inherited trauma, how it can snake through generations, warping the branches of a family tree, setting descendants along paths they aren’t sure why they’re walking. But what if you could immerse yourself in the memories of your ancestors? Taste what they tasted, see what they saw, fear what they feared? How would that change you? The first two arcs of Black Magick have been subtitled “Awakening.” In issue six, this title gains more resonance, interrogating inherited trauma and the trials and wonder that comes with great power. It exemplifies the attributes that have come to define the second arc — touches of horror glittering at the edges of the story, a blend of noir-tinged mystery, and a finely tuned understanding of the men and women that populate the panels. This is why Black Magick is a comic that deserves to be read and studied. It offers propulsive action, evocative horror and noir, and beautifully emotional drama while putting the gaze of its complex heroine at the forefront.