Spoilers ahead for season two of Dear White People.

Season two of Justin SimienÔÇÖs Dear White People is exponentially more ambitious than season one. I was quite taken with it ÔÇö for more, read my review here ÔÇö because itÔÇÖs constantly thinking about how to present a moment in a visually striking yet dramatically appropriate way.

To get some insight into the choices the series makes, I asked Simien to talk to me about one of the episodes he directed this season, ÔÇ£Chapter VIII,ÔÇØ a two-character play set largely inside the radio station where the titular show is broadcast. We talked about the writing, direction, and performances of that episode in detail, but toward the end we talked about several more episodes, and the series as a whole, focusing not just on the story that was being told, but how Dear White People told it.

Why did you decide to spend most of the episode in the radio station with just these two characters, Sam and Gabe, and essentially turn it into a two-character play?

We plotted out the season and when we got to that point, we asked ourselves, Well, what if we just had it all out? Obviously the tension between Sam and Gabe has been building over the course of this season, and it just came up in the room ÔÇö what if we did a play? Two characters in a room?

ThereÔÇÖs a long tradition of filmed plays. In fact, some of the most highly regarded Hollywood films of certain eras, like Sidney LumetÔÇÖs 12 Angry Men in the ÔÇÖ50s and Mike NicholsÔÇÖs WhoÔÇÖs Afraid of Virginia Woolf? in the ÔÇÖ60s, were stage plays put on film. You had a very small group of characters working things out on one main set. And there wasnÔÇÖt too much of an attempt to ÔÇ£open the story up,ÔÇØ as producers like to say, by adding scenes or locations.

Yes. Mike Nichols and Sidney Lumet are two of my absolute heroes. As a filmmaker whoÔÇÖs somewhat known for being, I guess, flashy, or creating these very high presentational scenarios, this, on a craft level, felt like an absolutely delicious challenge. Jack Moore, who wrote the episode, comes from a playwriting background. I come from a theater background. And it just felt not only like the right way to handle Sam and Gabe, but also the right way to handle all these arguments that people are trying to have online right now but never really have in person.

Ultimately, this episode was the nexus of why I do the show. I get to be cinematic and tell stories about characters who normally donÔÇÖt get the cinema treatment. But then I also really get to have these sort of meta-arguments. The episode really works on a few levels.

Walk us through the levels.

ItÔÇÖs about Sam and GabeÔÇÖs┬árelationship, of course. But itÔÇÖs also the kind of conversation that I think white allies, or would-be white allies, and black folks are trying to have. And on a completely other level, itÔÇÖs a statement about arguments in and of themselves, and about the limits of being able to articulate a point. They both are so, so fricking right that it doesnÔÇÖt even matter by the end of it!

Did you shoot every part of the episode in a specific way according to a predetermined plan, or did you try a lot of different shots and camera moves in each scene, then edit together the stuff you thought worked?

IÔÇÖm very deliberate. I really loathe the trend towards lots of coverage now in directing. I never come into a scene and just shoot [everything from a lot of angles] thinking I can figure it out later during editing. We donÔÇÖt really have time on this show anyway. We shot it in three days.

This episode? Even by TV standards, thatÔÇÖs not much time. How did you get what you needed?

I spent a lot of time [before shooting] with the actors, figuring out what the beats of the episode were, the beats of the scenes, and then came up with the philosophy of how I wanted to portray that ÔÇö how I wanted to visually portray whoÔÇÖs winning, whoÔÇÖs losing. When do we have a glaze against the lens of the camera? When does the camera move? When are we going to do a canted angle? So when we moved in to shoot it, the process was very deliberate. Because we shot it in three days, and because it was just two characters, we had those rare instances where we were able to rehearse the whole thing a couple of times.

When you rehearse your actors, is it just you and the actors, or does a camera come into the process? In other words, are you working out the shots while youÔÇÖre working out the performances?

To me, itÔÇÖs the same thing. What I want to see is whatÔÇÖs organic, what the actors are bringing to it. I like to get into a really heavy discussion of what the beats are. When is there a tactic shift? When is there a revelation? When does the balance of power shift? The actors and I talk about that and decide that together.

Based on those beats. I come up with my philosophy for this episode. When characters are shortsighted, our angles are canted, or the camera moves, or itÔÇÖs shaky. All of that means something to me, and that was decided during the rehearsal process based on what we felt the script was trying to get us to do.

Can you give me an example from ÔÇ£Chapter VIIIÔÇØ of a moment where youÔÇÖre directing in a certain way, and then suddenly youÔÇÖre directing in a different way, and itÔÇÖs because of something that happened between the characters?

Yes. ThereÔÇÖs a moment when Sam and Gabe are going back and forth very early in the scene. We are in these very canted angles where Gabe looks very isolated and almost trapped because heÔÇÖs literally in SamÔÇÖs range.

ThereÔÇÖs a moment where he thinks sheÔÇÖs being sweet, and she lets him know that sheÔÇÖs going to record this. He asks if itÔÇÖs insurance against him taking her words out of context, because he would never do that.

And she says, ÔÇ£Not now, you wonÔÇÖt.ÔÇØ

Suddenly, we cut outside the room and we see the glare of the light from the glass and we realize, ÔÇ£Oh, GabeÔÇÖs in the ring.ÔÇØ

So we stay on inside of the blind for the majority of that conversation while theyÔÇÖre going back and forth.

And then Gabe makes his first slam dunk. Sam says, ÔÇ£There are ways to speak out that donÔÇÖt scream ÔÇÿLook at me.ÔÇÖÔÇØ

And then Gabe says, ÔÇ£Are there? If so, they seem to have eluded you.ÔÇØ

Right! And then you cut to a high angle, which literally gives you a bit of distance from the moment. And how appropriate it is that you talked about this space as a boxing ring. The characters are smaller in the frame, diminished. ItÔÇÖs like a shot of a boxing ring, where youÔÇÖre between rounds and the fighters have gone to their corners.

Yeah! And then suddenly we cut, and now weÔÇÖve flipped, and weÔÇÖre on the opposite side of Gabe and Sam. WeÔÇÖre shooting through a different window than the last one we shot through, because now Gabe has the upper hand in this match. Then Sam takes her jacket off and has to shift, because GabeÔÇÖs response really just hit her in the gut.

My direction changes here because the balance of power has now shifted in GabeÔÇÖs favor, and now heÔÇÖs able to put Sam under his microscope for a change. ThatÔÇÖs one of the moments in the episode where you feel a shift in tactics thatÔÇÖs mirrored by the camerawork.

What difference does it make if you shoot an episode of television in this deliberate, structured way as opposed to shooting from a bunch of different angles and putting it together later? A lot of TV shows are shot that other way.

Yeah, they are. But to me thatÔÇÖs not cinema, thatÔÇÖs not visual storytelling, and I love cinema. ThatÔÇÖs what I love. I donÔÇÖt have a problem with the other kind of storytelling.┬áI think it works very well for TV. But I believe a moment has a bigger impact on the audience when the camera, the director, the writing, the actors, are all in cahoots. ThereÔÇÖs certainly something to be said about cinema verit├®, for finding it as you go, but thatÔÇÖs not what gets me excited about filmmaking. The filmmakers IÔÇÖve always loved are filmmakers who do everything with intention. Whether or not youÔÇÖre even aware of what the camerawork is doing, aware of where you place the camera, aware of what angle itÔÇÖs at ÔÇö is it above the eye? Below the eye? Close to the face with a wide-angle lens? Away from the face but zoomed in? ÔÇö all of that has a subtle effect on your emotions and the way you perceive the scene. The choices you make as youÔÇÖre shooting can increase the tension, decrease it, amp up this moment.

I always try to keep my ear and my eye open for things I didnÔÇÖt think of, of course. But I do very little that isnÔÇÖt intentional. I am not a haphazard director. I think everything that can be chosen should be chosen.

IÔÇÖm curious how you maintain stylistic consistency on a show thatÔÇÖs as deliberately directed as this, but where you also have a lot of writers and directors who arenÔÇÖt Justin Simien. What kind of directors do you like to have on the job, and whatÔÇÖs the process like for them when theyÔÇÖre directing for you?

I vet for cinematic directors. The process is, ÔÇ£On this job, you get to tell the story the way you as a filmmaker instinctively want to tell it.ÔÇØ Some of them storyboard or [do a] shot list.┬áSome of them donÔÇÖt. But the thing that unifies all of them is that they all have a point of view, and the way they make their stories is completely intentional. Janicza [Bravo] directs in a completely different way than Salli Richardson, or Steven Tsuchida, or Kevin Bray, but they all have a style that is about their POV and they all love making choices as filmmakers that accentuate the story in ways that were not intended in the script. Part of my job is to give them permission to do that, because you usually donÔÇÖt get to do that on TV shows, and then make sure that theyÔÇÖre not falling too far out of the Dear White People parameters.

What are the parameters?

I do make a style guide, not so much to make sure people direct it the way I would, but to let them know what choices mean to me, so if they do something different, then itÔÇÖs for a reason.

Can we do a lightning round here where I throw out the names of a few of my personal favorite episodes this season, and maybe you could identify moments that land for you, in the way that those two specific moments in ÔÇ£Chapter VIIIÔÇØ landed for you?

Sure.

First up is ÔÇ£Chapter IV,ÔÇØ written by Njeri Brown and directed by Kimberly Pierce of Boys DonÔÇÖt Cry. This is the episode where Coco realizes sheÔÇÖs pregnant and has to decide whether to terminate the pregnancy or give birth.

I like when sheÔÇÖs at the mirror. SheÔÇÖs feeling her belly and imagining what it might be like to be pregnant. I thought that said so much, without any dialogue, about where CocoÔÇÖs headÔÇÖs at.

I love the shot where the camera is so low it looks like it might be under the floor. YouÔÇÖre looking up at CocoÔÇÖs belly, and it looks like itÔÇÖs twice the size of her head.

Yeah! ThatÔÇÖs a beautiful shot. Kim is such a great filmmaker, and she has an exhaustive amount of cinema knowledge and understanding that she brings to her work. The script is great, but thatÔÇÖs a beautiful moment that Kim Pierce invented that wasnÔÇÖt in the script. She called me up and she said, ÔÇ£I really think we need this moment.ÔÇØ

Talk to me about ÔÇ£Chapter V,ÔÇØ directed by Salli Richardson-Whitfield and written by Leann Bowen. Joelle has a brief fling with a guy in her chemistry class and finds out that heÔÇÖs all wrong for her.

I love all the Annie Hall moments, like when she faints dead away. I thought that was so quirky and fun.

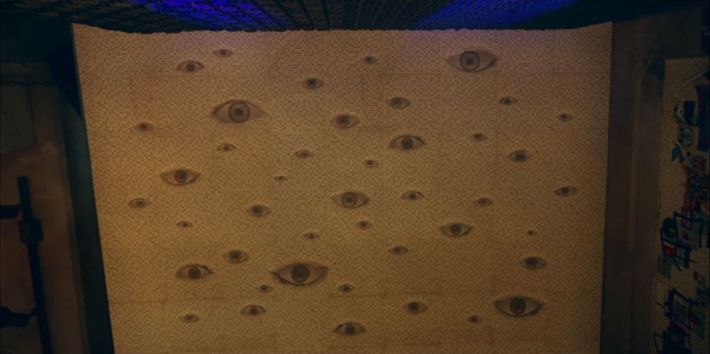

ÔÇ£Chapter VII,ÔÇØ TroyÔÇÖs drug drip. Directed by Steven Tsuchida, written by Yvette Lee Bowser and Nastaran Dibai. You get trippy with the imagery.┬áItÔÇÖs a little bit like the Mad Men episode ÔÇ£The CrashÔÇØ or the Barney Miller episode where they eat the hash brownies.

Exactly! Both of those episodes were inspirations for us. Also, the The Simpsons episode where Homer has the really hot chili! ThatÔÇÖs the one that was going through my head the whole time in the writers room when we were putting everything together.

My absolute favorite moment of that episode is the conversation with Sorbet the dog. I remember we had a lot of conversations about that scene with the network. I was just like, ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs gonna work! IÔÇÖm telling ya, itÔÇÖs gonna be so great!ÔÇØ Especially when weÔÇÖve got Loretta Devine, of all people, voicing this very esoteric but also just mean monologue to Troy through a very cute dog! ItÔÇÖs one of my favorite moments of the series.

I felt like I was on drugs when that scene came on.

Good! Then we did our job.

And finally, ÔÇ£Chapter IX,ÔÇØ written by Nastaran Dibai and Yvette Lee Bowser and directed by Janicza Bravo, where Sam goes home. First of all, I have to ask you, am I forgetting something or is this the first episode that takes place out of the college entirely?

Not exactly. There is a moment last season where Lionel and Troy go to an off-campus bar, but thatÔÇÖs still within the town of the college.

I donÔÇÖt think that really counts, though.

Well, youÔÇÖre right that this absolutely is the first time we go home with a character and leave the milieu of Winchester. You can feel the difference. The heightened reality of the show falls away the longer sheÔÇÖs at home, and I was just so incredibly excited by the idea of doing that. I really resisted doing it in the first season.

What, leaving campus?

Yeah. It was very intentional to stay at Winchester. But this just felt like the time to do it, and Janicza felt like the person to take us there. Her POV is singular. If you look at her movie Lemon, she has a way of taking everyday moments and finding what is surreal in them, whereas we tend to take surreal moments and try to bring them back down to reality for the rest of the show.

But the other thing is, weÔÇÖre at home, and it really is the first time for Sam, who weÔÇÖve seen a lot of through the film and the show, giving us a real look underneath her persona as this Afrocentric leader on campus. We go to a space where she is vulnerable. WeÔÇÖve never seen Sam like that. So much of what you see of Sam is the person who is strong, articulate, and fighting. She is in her persona at Winchester, but she canÔÇÖt be in that persona at home. ItÔÇÖs also very familial. You see all kinds of age groups back at SamÔÇÖs home, where normally weÔÇÖre seeing a bunch of kids who are about the same age onscreen. The episode feels conversational. It feels like what itÔÇÖs like to go home. A lot of that has to do with the way Janicza directs and puts her scenes together.

Naturalistic is the word, but at the same time ÔÇ£Episode IXÔÇØ also feels like what I call an ÔÇ£incidentally metaphoricalÔÇØ story. Sam is a biracial woman, and when we go into her family house for this gathering, itÔÇÖs populated by a mix of black and white people. So itÔÇÖs like weÔÇÖve gone inside of her mind, in a way.

That was absolutely the intention. We asked ourselves, what are the conflicting voices in SamÔÇÖs head? Then we tried to personify them in the form of her family. That was one of the fun parts about it. And itÔÇÖs also a girlsÔÇÖ trip, itÔÇÖs the first time you see these particular three black women together. ThereÔÇÖs a communion between them that wasnÔÇÖt there before.

ItÔÇÖs a special episode for a number of reasons, in part because of all the stuff you really canÔÇÖt put your finger on as a viewer because itÔÇÖs so personal. We really do put our personal stories in the show. IÔÇÖve lost a parent. So many of us have lost a parent. And particularly when youÔÇÖre the product of a biracial relationship, going home gets very complicated, for reasons that arenÔÇÖt often covered in TV or film.

How many seasons can Dear White People go on? Are you going to keep the same cast, or at some point are you gonna have them turn into faculty members, like Leroy on Fame?

You can absolutely go for as long as people are interested in watching, and I donÔÇÖt even think they have to become faculty members! They can just graduate! [Laughs.] New people might be able to capture your attention!

But really, I think it can go for as long as I have stories to tell in this space. So much of the show is inspired by the [audience] response to it, and by whatÔÇÖs happening in the culture. I donÔÇÖt have a massive plan as to when it ends. ItÔÇÖs just about, ÔÇ£Do I have something to say right now?ÔÇØ and right now I do. WeÔÇÖre really ambitious about this second season, and IÔÇÖve kind of thought about it as going as far as a season four. But the nature of doing a Netflix show is that you do have to wait to find out if youÔÇÖre picked up. I try not to put cart before the horse,

Wait  if you havent officially been renewed yet, youre taking a hell of a risk with that ending, arent you? Like I said in my review, its not just a cliffhanger, its so flagrantly enjoying the idea of being a cliffhanger that you might has well have shot it on an actual cliff.

Yeah! But whatÔÇÖs the point if you donÔÇÖt take risks, you know? I feel really good about it, but you just never know!

Is Giancarlo Esposito Voldemort?

[Laughs.] No, heÔÇÖs not Voldemort! Giancarlo Esposito is not Voldemort.

This guy who emerges from the darkness in this underground catacomb and sounds just like our narrator, is he real? Is he figurative? Is he a ghost?

IÔÇÖm not telling you that!

You had the narrator join the cast! If thatÔÇÖs not nuttier than the poodle that talks like Loretta Devine, itÔÇÖs definitely close!

I donÔÇÖt think you really want me to tell you that!

Of course I donÔÇÖt! But can you at least tell me if he lives down there in the basement?

I donÔÇÖt think he lives in the basement. But I will tell you this: We had a lot of conversations about bringing the narrator into the narrative. ItÔÇÖs something IÔÇÖve really wanted to do since the beginning of this particular season. IÔÇÖm conscious about having a narrator at all, and I never want to use it as a crutch. I always want it to be a vital part of the series. The writers know who [the character in catacombs] is, and what he means.

But there are a number of places we can go from here, and a lot of that has to do with factors that are beyond our control, such as what actors are available, how much money we have in the budget, and when we get picked up.

Do you have a road map for a third season, if Netflix gives you one?

All IÔÇÖll say is we have an idea of where the story is going, but just like with last season, life comes at you fast and could take us in directions that we find more interesting.

IÔÇÖll also tell you that thereÔÇÖs a lot of stuff that we planted in season one that we havenÔÇÖt paid off yet, and you probably wonÔÇÖt figure out what I mean by that until we do pay it off. WeÔÇÖre always trying to open doors that lead to interesting spaces. That is our mantra in the [writers] room, because it is an expansive universe.

Right, I can see that. But at the same time, this show is very much another example of something that Dan Harmon said to me years ago, that ultimately all great TV shows are GilliganÔÇÖs Island, in the sense that they create their own little world, and once theyÔÇÖve created it, thatÔÇÖs the world and they almost never leave it. And when they do leave, itÔÇÖs for a reason.

Sometimes a show creates a geographically huge world, like on a Star Trek series or Game of Thrones. But more often on television, itÔÇÖs a medium-sized or small world, like the world of your college campus. On hospital shows and cop shows, often, itÔÇÖs the hospital or the police station where 90 percent of the scenes are set. YouÔÇÖre making one of the contained shows.

Yeah ÔÇö and you know, I really like that GilliganÔÇÖs Island philosophy. But what may surprise you is how big our island is. That might be the thing that surprises people as the show goes on.

You also gotta realize, weÔÇÖve been experimenting with time since the first season. I think the idea of going into the future, or an alternate future, and seeing that work, and how people are responding to it, has been quite exciting.

Like the episode with CocoÔÇÖs pregnancy? At the end, the show jumps forward 20-some years, to a future where she became a mother.

Yeah. And doing that kind of thing started to make me think about what it might be like if we were to continue to do that.

ThatÔÇÖs interesting. Having spent time in an alternate future for one character this year, I guess thereÔÇÖs nothing stopping you from doing that again in another episode with a different character, or doing it for an entire 30-minute episode.

Exactly. As much as the show is about racism, we just also really love storytelling. We get very excited about finding a way to twist the screws, or do a variation on a theme.

ItÔÇÖs interesting that you brought up Dan Harmon, because I think one of the very best shows on TV is Rick and Morty. What I love about that show is that theyÔÇÖre constantly, sometimes exhaustingly, playing with, referencing, and subverting the form. Because our show is all about subverting expectations and showing you that a person you think you know something about is actually a totally different person, thematically the format gives us a lot of room to do things like that ÔÇö to try out alternate futures or timelines.

Our show, at its core, is really all about how this book that youÔÇÖre holding in your hand is not what you thought it was. The cover of the book led you to believe itÔÇÖs one thing, but in fact itÔÇÖs something completely different.

This interview has been edited and condensed.