The rousing action-thriller Manhunt, out Friday, is a stylistic trip down memory lane for fans of John Woo, the Hong Kong filmmaker whose instantly recognizable style of meticulously choreographed gunfights are now synonymous with white doves and slow-motion gunplay. Manhunt is Woo’s remake of the 1976 Ken Takakura film of the same name, a The Fugitive-style melodrama about a principled Chinese pharmaceutical lawyer (Hanyu Zhang) who is framed for murder and hunted down by a rebellious, but fair-minded, Japanese cop (Masaharu Fukuyama). Manhunt is also Woo’s self-conscious homage to the movies that influenced his own formative action films, like A Better Tomorrow (1986), The Killer (1989), and Hard Boiled (1992).

Now, just days before Netflix’s release of Manhunt, Woo has announced that he will direct a remake of The Killer starring Lupita Nyong’o as Chow Yun-fat’s assassin with a heart of gold. This is only fitting, since the original Manhunt is one of The Killer’s biggest acknowledged inspirations, along with Jean-Pierre Melville’s Le Samouraï and Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch.

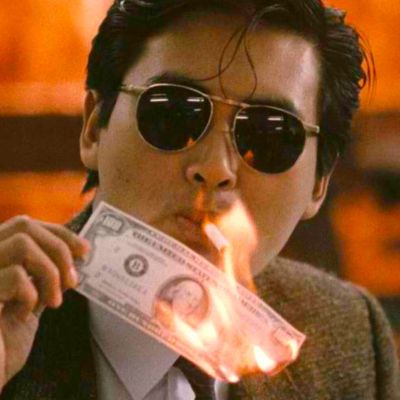

Like Peckinpah’s antiheroes, Woo’s protagonists are typically men who live in a fallen world and consequently die by their outdated principles. The most potent image in Woo’s filmography is the prefatory A Better Tomorrow scene, where Chow lights a cigarette with a burning counterfeit C-note: Money is meaningless in a world where everybody wants power, but nobody cares who they screw over to get it. Woo understands this type of skid row desperation, since he only escaped poverty with the sponsorship of the Chinese Christian Church. Woo’s Christian influence can be seen in his most vile-seeming characters, who are frequently humanized through plot twists and reversals of fortune. There’s also a predestination-style fatalism that suggests some well-meaning characters cannot change — not without the sacrificial help of an even more selfless (male) comrade.

If you’re not yet familiar with Woo’s work — or just want to brush up — Vulture has compiled a primer of ten revealing and worthwhile Woo titles in anticipation of Manhunt’s release.

1) Hand of Death (1976) and Last Hurrah for Chivalry (1979)

Woo’s pet concern with money’s corrupting influence goes as far back as his successful, Jerry Lewis-inspired comedies, Money Crazy (1977), in which a luckless schlub tries to impress a girl by stealing a diamond that’s protected by a twitchy hitman; and From Riches to Rags (1980), which concerns two soda-delivering coolies whose lives go to hell after they win the lottery. But you can also see early flashes of Woo’s personality in Hand of Death and Last Hurrah for Chivalry, two martial arts films in which the action choreography and sense of honor-bound heroism both bear the influence of martial arts filmmaker Chang Cheh. Chang hired Woo to work as his assistant director on kung fu films like The Water Margin (1972) and The Blood Brothers (1973); that experience propelled a then-27-year-old Woo to sign a three-year contract with Golden Harvest’s production studio (a deal that Woo would soon grow dissatisfied with).

In Hand of Death, an elite group of Shaolin warriors (including Jackie Chan) fights a seemingly unstoppable killer (James Tien) who wants to eradicate China’s Shaolin temples. Chan’s group rallies against Tien’s ferocious antagonist, but are met with considerable resistance. Hand of Death ends on a melancholic note that presages the cynicism of Woo’s more mature movies. Also noteworthy: while Chan isn’t the film’s star, Woo did give Chan one of his first big breaks (Chan was, at the time, better-known as a bit player and stuntman). Last Hurrah for Chivalry is equally grim: a pair of assassins (Wei Pai and Damian Lau) seek revenge against an evil martial arts master, but are slowly revealed to be working at cross purposes. This secret rivalry speaks to the way that many adversarial relationships in Woo’s films are complicated by hidden allegiances that are only revealed through unforeseeable plot twists.

2) A Better Tomorrow (1986) and A Better Tomorrow II (1987)

Woo made A Better Tomorrow after a brief creative slump, when both he and TV star Chow were considered box office poison. Still, Woo refused to make more martial arts films in spite of their unflagging popularity. So he drew inspiration from the 1967 gangster film Story of a Discharged Prisoner, and made A Better Tomorrow with the help of producer Tsui Hark (Once Upon a Time in China, Detective Dee: Mystery of the Phantom Flame). In A Better Tomorrow, two estranged brothers — Leslie Cheung’s fresh-faced cop Kit, and Tam Fu-wing’s jaded crook Ho — struggle to reconnect after Ho serves three years in prison. This relationship was loosely inspired by Woo’s real-life friendship with Tsui, whose fortunes rose as Woo’s fell. The film’s action choreography is still impressive, especially during the scene where Chow, as Ho’s disillusioned partner Mark, uses four carefully concealed guns to blow away a roomful of gangsters. But Chow is the X-factor that puts A Better Tomorrow over the top. Woo reluctantly helmed a preposterous sequel to A Better Tomorrow after his 1986 original became a record-setting box office smash, but he let Tsui direct the mostly tedious second sequel.

3) The Killer (1989)

Arguably the ultimate expression of Woo’s style, The Killer follows two hyper-focused/hyper-serious professionals — Danny Lee’s reckless cop and Chow’s well-meaning assassin — as they chase each other and inevitably bond. Chow’s anti-hero is somewhat humanized by his ward-like relationship with Jennie (Sally Yeh), a singer he accidentally blinds during a hit job gone wrong. But there’s no real chemistry between these two leads. By contrast, Lee and Chow’s characters form an iron-clad bond during The Killer’s famous slow-motion church shoot-out. Shot over the course of 28 days, this sequence speaks to Woo’s infusion of Protestant/Christian imagery: the doves, in Woo’s words, “represent the purity of love [… and are] the messenger between people and God,” and the exploding Virgin Mary statue “is destroyed by evil, and with it the spirit of chivalry displayed by ancient warriors.”

4) Bullet in the Head (1990)

This grueling, Mean Streets-inspired Vietnam War film is considered by many fans — including this writer — to be Woo’s best and most personal film. It’s a sort of tragic buddy film about a group of opportunistic Hong Kong friends (led by Tony Leung) who fight and self-destruct over women and gold. Bullet in the Head is also Woo’s protest against the universally corrupting nature of political strife, as we see in an early scene set during the 1967 Hong Kong riots, and then later in sequences that recreate/allude to the Tiananmen Square protest and the now-infamous Saigon execution photo (Woo was an anti-Vietnam War activist in 1969 and 1970). Woo’s actors have great chemistry, and the film’s action set-pieces are just as tense and well-orchestrated as Woo’s more prominent films. That said: Bullet in the Head will always be considered by some — especially Woo — to be a missed opportunity, since the only extant version of the film is missing almost 45 minutes of footage (Woo says that the missing film reels were destroyed by Golden Princess, the film’s distributors).

5) Hard Boiled (1992)

Woo’s oft-imitated, but rarely matched action film — in which Chow and Leung play cops who try to stop evil gangsters (led by Anthony Wong) from destroying a Hong Kong hospital — is also probably his most combustive. Once again, Woo gets great mileage out of scenes where Chow fires two guns in the air, especially during the opening teahouse shoot-out. And you won’t find a better showcase for Woo’s meticulous action choreography than the film’s half-hour-long hospital set piece. These scenes, shot in 35 days, are also why Hong Kong crew-members used to tease Woo for his humorless perfectionism with nicknames like “Headmaster” and “Black-faced God” (Woo: “Maybe I was too stern.”). Woo would do anything to get the shot: “Every action scene I make, the whole scene is all in my head. I know exactly what I’m doing and what I want.” During the making of Hard Boiled, Woo supposedly yelled at cameramen if they didn’t get close enough to the explosions that Wong’s heavies detonated around the hospital: “Pick up the damn camera, and go into the fire!”

6) Hard Target (1993)

Production difficulties mar this unhinged New Orleans-set riff on The Most Dangerous Game, the first of Woo’s American projects. For example, Woo was blamed for being four days behind schedule after working 12–14 hour days, six days a week for about six weeks. Thankfully, Woo’s fussiness pays off big time during the film’s over-the-top, stunt-intensive action scenes, like its unbeatable motorcycle chase. Jean-Claude Van Damme, who asked to work with Woo after seeing his earlier films, is saddled with some truly perplexing style choices (that rat tail??) and dialogue, though Darkman scribe Chuck Pfarrer claims that the rewriting process made Van Damme’s dialogue better suit his persona (despite also “losing some bits of subtlety”). But while Hard Target is for fans only, its tonal rockiness also speaks to how difficult Woo’s initial Hollywood transition was.

7) Broken Arrow (1996)

Woo took on this special-effects-intensive spy thriller for the same reason he would later become dissatisfied with it: it wasn’t within his comfort zone, since he hadn’t really worked with computer-generated imagery (CGI). The film, which pits Christian Slater’s good guy Air Force pilot against John Travolta’s bad guy pilot in a quest to disarm a stolen experimental nuclear bomber, isn’t Woo’s standard fare. But you can see that his intuitive approach to working with actors works here since Travolta and Slater both play so well against type and each other. Broken Arrow was also Woo’s first hit in America, though working on this assignment left him feeling like a hired gun.

8) Face/Off (1997)

Face/Off (or, the punch-drunk action film where Nicolas Cage and John Travolta play a cop and robber who swap faces) is the make-or-break point for Woo fans: if you love it, you’re probably a diehard Woo buff. Before it was theatrically released, Woo promoted Face/Off as the first Hollywood production where he had enough creative freedom to make a semi-personal film. Unfortunately, his film’s frequently berserk tone is as alienating as it is endearing. See, for example, the scene where Olivia Newton-John’s cover of “Over the Rainbow” is used to signal the loss of innocence (Woo often cites The Wizard of Oz with sparking his life-long affection for musicals). Still, Face/Off’s major set pieces are mostly as thrilling as you might hope, especially the big prison riot set piece. But Cage is also stratospherically campy, a decision that he and Woo reached together (and that led Cage to re-team with Woo on the Sam Fuller-esque Windtalkers). You may enjoy Face/Off if you go in expecting it to be off-the-rails screwy. You also might enjoy this fun, but relatively staid novelization.

9) Blackjack (1998)

Speaking of hired guns: Woo considered several projects before taking on this deliriously silly TV pilot, including a film version of Andrew Lloyd Webber’s Phantom of the Opera (of which he was a big fan). And while Blackjack is not one of Woo’s best films, it’s very enjoyable if you’re in the mood to watch Dolph Lundgren play Jack Devlin, a retired U.S. Marshall who is wrestling with a crippling fear of the color white. That’s not an exaggeration: in addition to raising adopted daughter Casey (Padraigin Murphy), Jack must cope with leukophobia after an old friend (Fred Williamson!) hires him to protect a supermodel (Kam Heskin) from a creepy stalker (Phillip MacKenzie). Lundgren is often too bulky and uncoordinated to credibly pull off Woo’s signature gunplay. But the film’s chase and fight scenes are thrilling, and so is any standoff where MacKenzie’s villain disarms Devlin with, uh, white sheets and milk. Keep your eyes peeled for Warehouse 13 star Saul Rubinek as Jack’s eyepatch-wearing manservant.

10) Red Cliff (2008 and 2009)

This two-part, five-hour-long war epic deserved so much better than the pitiful American release that Magnolia gave it in 2009. Instead of releasing the film’s original 288-minute cut, Magnolia released a hideously shortened 140-minute version, one where the film’s spectacular battle scenes are sped up just so they literally move faster. That’s not an exaggeration: The US release of this film has set pieces that are paced at a Benny Hill-fast rate because international audiences (i.e., America and the UK) were presumed to be too impatient to watch a two-part, foreign-language war film (for more details, see my old Slant Magazine review here). Granted, Red Cliff was explicitly designed to appeal to Chinese language speakers since it takes place at the end of the Han dynasty, a historic period made famous by the mega-popular Chinese novel The Romance of the Three Kingdoms. But Red Cliff’s measured tone, and consistently engrossing plot, makes this ambitious drama Woo’s last great film. For now.