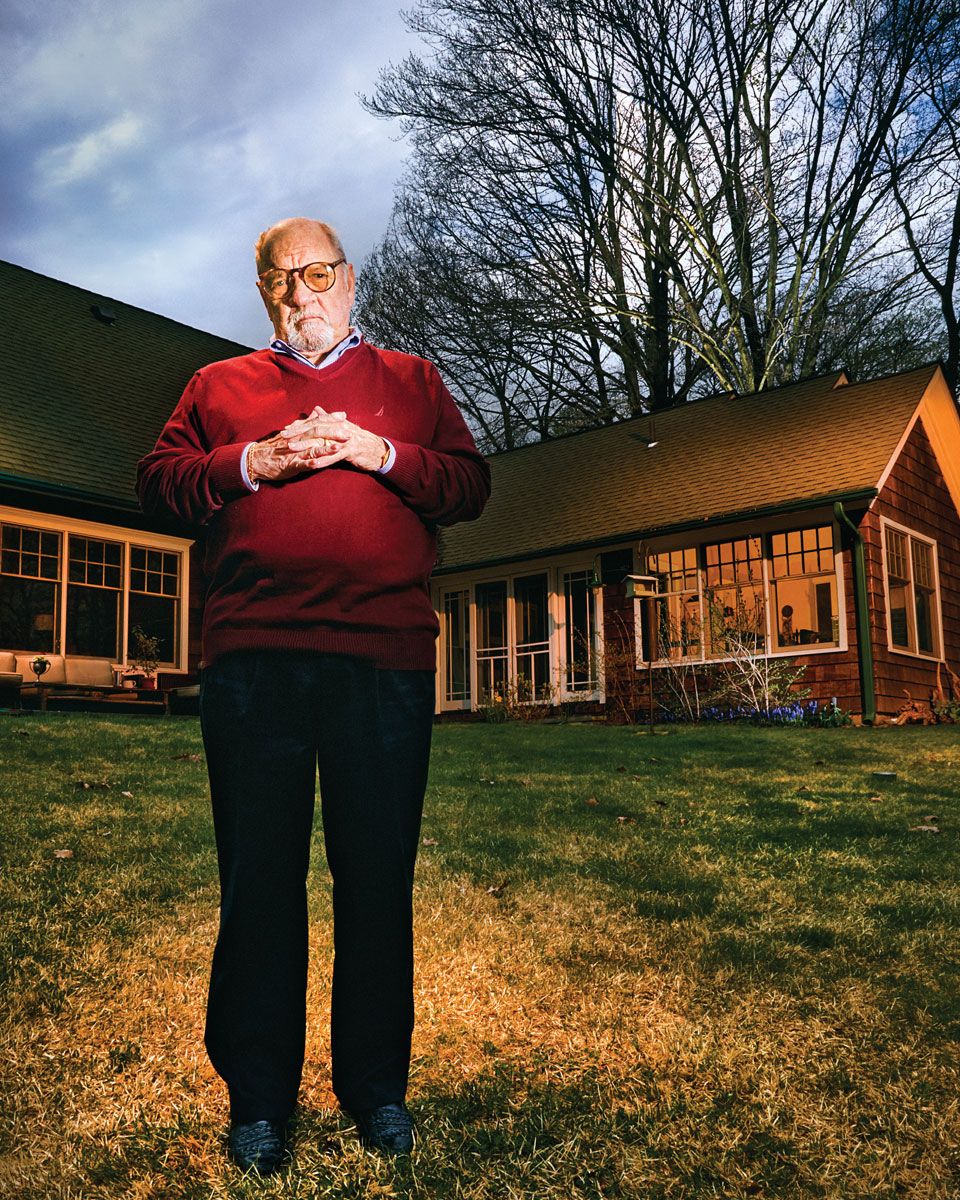

When Dying of the Light was released in 2014, its writer and director, Paul Schrader, thought his career was over. The film, which starred Nicolas Cage as a CIA agent trying to catch a terrorist before losing his mind to dementia, had been taken out of Schrader’s hands because he’d deviated from the formula set by the movie’s financiers, which predicted that if it included x number of action sequences in y number of minutes, they’d earn z percent on their investment. (The financiers said Schrader’s cut of the film differed from his original script; Drive director Nicholas Winding Refn, an executive producer on Dying of the Light, says Schrader’s version was “absolutely terrific.”) If the predicament sounds beneath the screenwriter of Taxi Driver and Raging Bull and the director of American Gigolo, Blue Collar, and Mishima, that’s because it was. “I never cared that much for final cut in the past, because you were always dealing with studio heads who were movie people — they all liked movies. But now I was dealing with financial people,” says Schrader, 71. “That was a very, very bad experience. I spiraled into alcoholism and depression, and I thought that was it: The last film in my career was going to be a fiasco.”

Luckily, he was wrong. We’re sitting in the garden terrace of the Chateau Marmont’s restaurant discussing his new movie, First Reformed, a non-fiasco. The New York–based Schrader has come down to Los Angeles for the day from San Francisco, where he just showed the film; he’s been making the festival rounds, including Venice, Telluride, and New York — A24 snapped it up at Toronto — where it’s been greeted as Schrader’s masterpiece, the culmination of career-spanning obsessions.

In First Reformed, a pregnant woman named Mary, played by the actually pregnant Amanda Seyfried, comes to Ethan Hawke’s Reverend Toller, a despondent, alcoholic minister at the First Reformed Church in upstate New York, begging him to talk to her environmentalist husband, Michael (Philip Ettinger), who can’t square his impending fatherhood with the ecological collapse he believes is just decades away. “Can God forgive us for what we’ve done to this world?” Michael asks Toller, a question that, in the hands of some writers, might remain a rhetorical one. But for Schrader and his reverend, this idea becomes a movie-length confrontation between the nature of faith, capitalism’s role in organized religion, and man’s responsibility to nature.

“Most contemporary movies don’t ask you to think; they don’t ask unanswerable questions,” Hawke says. “A lot of filmmakers have an agenda: They’re trying to convince you to think the way that they think. What Paul is doing is my favorite thing a filmmaker can do, which is present life to you so that you ask yourself these questions.”

By this point, Schrader’s biography is part of Hollywood legend, but it may have more bearing on First Reformed than any of his other films: He grew up with strict Calvinist parents and didn’t see his first movie until he was 17 years old; he went to UCLA Film School thanks in part to a recommendation letter from Pauline Kael; he wrote the book Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer when he was just 24; and he wrote the screenplay for Taxi Driver a few years later. Lately, he’s shown himself willing to experiment and take risks. In 2013, he made The Canyons, a California noir starring Lindsay Lohan and the porn star James Deen, with a script by Bret Easton Ellis, funded partly via Kickstarter donations.

After the debacle of Dying of the Light, Schrader was approached to direct a crime thriller called Dog Eat Dog, and he saw an opportunity. “I had been talking to Nic, and I said, ‘Nic, we’ve got to work together again, we’ve got to get this stain off our clothes’ — of course, he’ll never get all the stains off his clothes,” Schrader says, laughing. “And this time, I said, ‘I will have final cut, and we’ll do exactly what we want.’ ”

“Exactly what we want” meant a gonzo pulp thriller starring Cage’s Humphrey Bogart impression. While it might not be headed for the Criterion Collection anytime soon, Dog Eat Dog is fun and idiosyncratic, and in a certain sense, it lifted enough stains for the director to embark on First Reformed.

It’s no accident that First Reformed coincides with the University of California Press’s republishing of Transcendental Style in Film — which assesses how Robert Bresson, Carl Theodor Dreyer, and Yasujiro Ozu withhold typical filmmaking elements like non-diegetic music, camera movement, editing, and the expressiveness of actors in order to evoke a sense of the spiritual. Schrader had recently begun rethinking Transcendental Style, and an encounter with the Polish director Pawel Pawlikowski, whose 2013 film Ida Schrader had loved, led him to finally make a movie of his own in that fashion.

“People would try to compare that book to the films I was involved in, and I would say, ‘No, I’m not that guy,’ ” Schrader says. “I like these films, but I’m just too intoxicated with action, empathy, sex, and violence, and those elements aren’t in the transcendental tool kit.” But Pawlikowski told Schrader that after receiving overtures from Hollywood, he’d had a revelation: As long as he could make a movie for under $2 million in Poland, he could do anything he wanted.

After Dying of the Light, the message carried a particular resonance.

Schrader made First Reformed in 20 days for $2.5 million, partnering with Christine Vachon’s Killer Films and Arclight Films, which also contributed to Dog Eat Dog, shooting in a version of transcendental style, observing rules that, on occasion, he breaks to great effect. When Richard Linklater saw it, he told Hawke that no one had even tried to make a film like it in decades.

In addition to the festivals, Schrader’s been taking First Reformed to seminaries, where he’s been gathering ammunition, in the form of support and praise from religious leaders, in case conservatives come after him, like they did following 1988’s The Last Temptation of Christ, which he wrote.

He acknowledges, though, that plenty’s changed since then. “Because we’ve democratized filmmaking, the good news is almost anybody can make a film; the bad news is nobody can make any money,” Schrader says. “Movies were born of capitalism: You pay for it, we’ll make it for you. There was no tradition of the courts and the church and all that. Therefore, it had a special relationship to capitalism that really protected it. Now that’s broken, and so it’s like every other art form: It’s like poetry, or novels, or painting.”

Though television is making money, and Schrader’s been impressed by its recent quality, he doesn’t think he’ll end up working in the medium. “TV isn’t as free as you think it is,” he says, explaining that Netflix and Amazon rejected First Reformed both when it was a screenplay and then again when it was a completed film. But he believes he’s got a film or two left in him, and has in fact begun writing a new project. With his First Reformed editor, he also recut Dying of the Light into a movie that he calls Dark, which, he says, goes from being a “Nic Cage film to a Stan Brakhage film.” He’s legally prevented from screening the cut publicly, but he managed to sneak a few clips into a lecture at Rotterdam that’s available to watch on YouTube.

Lately, he’s found a new perspective on the question that bothered him just four years ago. “That same feeling I had about Dying of the Light — is this going to be the end? — I’m having that feeling again. Only now it feels good instead of bad.”

First Reformed opens May 18.

*This article appears in the May 14, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!