When Todd Haynes was working on Safe, the 1995 film starring Julianne Moore as a housewife who becomes increasingly allergic to the world around her, he expressed frustration over the classification of “gay cinema.” It wasn’t that he felt the category was pigeonholing, like some might today, but rather that it should be more exacting. “People define gay cinema solely by content: if there are gay characters in it, it’s a gay film,” he said in an interview in the spring 1993 issue of Film Quarterly. “Heterosexuality to me is a structure as much as it is a content. It is an imposed structure that goes along with the patriarchal, dominant structure that constrains and defines society. If homosexuality is the opposite or the counter-sexual activity to that,” he asked, “then what kind of a structure would it be?”

The critique would apply to any number of films from the past decade that are nominally LGBT in content, but not queer in structure. We’ve entered a boom time for LGBT film, and the movies released in the past decade boast a mainstream appeal, with straight actors now more than ever willing to play an LGBT character. There have been Oscar-validated prestige pictures (Milk, The Kids Are All Right, The Dallas Buyers Club, Call Me by Your Name), and corresponding flops (Stonewall, Freeheld), indie films (Princess Cyd, Tangerine), and commercial middlebrow ones (Love, Simon). While these films vary in intent, provenance, and quality, they encapsulate a similar catholic spirit: rather than assert difference, they point out similarities. They apply salve instead of salt. They’re safe, often boring, and sentimental, following familiar emotional arcs to tell a “universal story.” In short, we’re in a movie moment defined by the political sensibility of the gay-marriage movement.

Depending on your viewpoint, the legalization of gay marriage is either the greatest recent civil-rights victory or a myopic apportionment of rights. It was a beloved cause for progressives, but a philosophically conservative one. The rhetoric — love is love (is love is love) — was generic and effective, suggesting that the only thing that separates gay people from straight ones was semantics. “More and more Americans [have] come to understand what this is all about is a simple proposition: Who do you love?” then–Vice-President Joe Biden said a few years before the Supreme Court legalized gay marriage nationwide in 2013, ten years after it become the prevailing LGBT issue. “I think Will and Grace did more to educate the American public more than almost anything anybody has done so far. People fear that which is different. Now they’re beginning to understand.”

The political language around sameness — that “they” are just like “us” — moved out of the ballot box and into film. Part of this is a rhetorical strategy to sell movies to a heterosexual public. Luca Guadagnino has called Call Me by Your Name a “family film”; Rachel Weisz called Disobedience, her recent passion project about a lesbian relationship in an Orthodox Jewish community in London, a “universal story.” Alia Shawkat, the star and writer of Duck Butter, a movie about a 24-hour relationship between two women, emphasized the importance of normalization. “Eventually I want to get to the point where we’re watching movies and the story’s not about the fact that they’re gay, or about the fact that they’re black, or about the fact that they’re trans — they just are. And we’re just watching that person’s life,” she told Vulture. “That’s how it becomes more normalized.”

Beyond discourse, the question of what makes a film queer has become subsumed by aesthetics and narratives that display a straight gaze. The most egregious example is one of the most recent: Love, Simon, a gay bildungsroman whose political and moral center is that its protagonist Simon is Not That Kind of Gay. Simon is a blandly handsome high-school teenager (Nick Robinson) who spends much of the film assuring the (hetero) audience that he’s just like them. “For the most part, my life is totally normal,” he says in the expository voice-over. He lives in a big two-story house; his parents are played by L.L.Bean catalogue models Jennifer Garner and Josh Duhamel; he gets a car with a big red ribbon on it for his birthday like a holiday car commercial. “I’m just like you except I have one huge-ass secret,” he says. “Nobody knows I’m gay.”

So what kind of gay is he not? Well, he’s certainly not like the only out gay student at his school named Ethan, a black femme student (Clark Moore) who delivers many of the movie’s only jokes. In a scene where a couple of jocks are bullying Ethan, Simon remarks, “I wish Ethan wouldn’t make it so easy for them.” When Ethan and Simon finally talk in the end, rather than have Ethan push back against just how good Simon has it, the film whiffs and has Ethan act as a sympathetic shoulder to lean on. Ethan remains a patsy, offering reassurance rather than resistance to the implicit assumption that Simon is “relatable” precisely because he’s white, masculine, and upper-middle class. The gravest injustice in Love, Simon is that a gay white boy couldn’t have grown up like a straight white boy.

It’s easy to castigate Love, Simon, but it’s the middlebrow iteration of a widespread sensibility that trades in sentimentality as a way to render LGBT people sympathetic. Prestige pictures go a step further, populating their stories with dying, saintlike queers who cut themselves open and offer up their tragedy for our moral edification, whether it’s Julianne Moore as the terminally ill Laurel Hester in Freeheld or David France’s uncomfortable fixation on Marsha P. Johnson’s death in the documentary The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson. (It’s no accident that “death” comes before “life” in the title.) The Oscar-winning Dallas Buyers Club chose to tell the story of the AIDS crisis through a homophobic straight white man Ron Woodroof (Matthew McConaughey), who realizes the error of his ways after he becomes HIV-positive. It isn’t until the end, after Rayon (Jared Leto), a drug-addicted trans woman, bequeaths him with largesse before she dies, that he too understands “community.” Her death sanctifies him and, in turn, the viewer who might harbor similar biases.

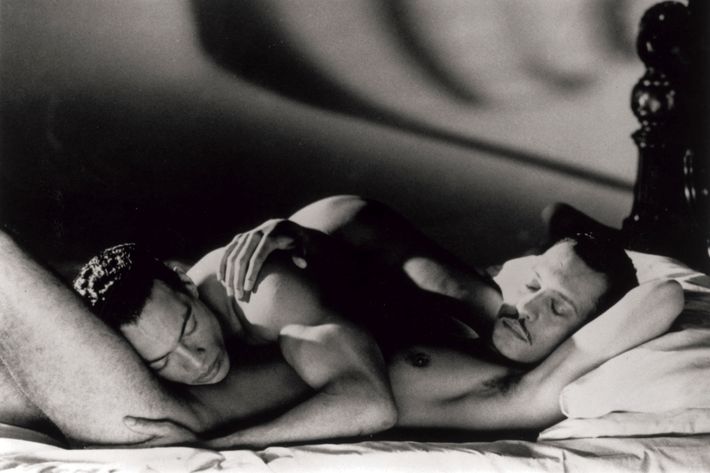

These are meek films that ask for both forgiveness and permission to exist. Think of the softness of Call Me by Your Name — a beautiful but anemic film that lacks the straight-into-your-veins immediacy of the original novel by André Aciman. When it comes to sex between the two protagonists, the teenage Elio (Timothée Chalamet) and grad student Oliver (Armie Hammer), Call Me by Your Name is practically demure. In the moment when Oliver and Elio have sex for the first time, the camera pans to look outside the window. When the pair arrive in Rome on a couple’s getaway, they get to the hotel room and start roughhousing as though they haven’t been having sex in secret for the past three weeks. The film stopped short, as though fearful of what might be considered prurient or in bad taste.

It’s no surprise, then, that we’ve seen a slew of biopics in recent years: movies that eschew the darkly sexual, depraved, or fraught aspects of biography in favor of empowerment. Gay films have become more concerned with the process of canonization, and the biopic is a favorite vehicle through which to legitimize historical figures, as Gus Van Sant’s Milk did with San Francisco politician Harvey Milk or The Imitation Game did with British WWII code-cracker Alan Turing. The 2017 Billie Jean King biopic Battle of the Sexes sanitized the complicated and disturbing aspects of King’s relationship with Marilyn Barnett to turn her into an equal-rights hero. Then there’s Roland Emmerich’s 2015 film Stonewall, which went so far as to whitewash history by creating a fictional protagonist — a young, white male character named Danny (Jeremy Irvine) — who moves to New York from the Midwest to throw the first brick during the Stonewall riots of 1969. He’s the surrogate through which we meet the real-life, historical figures of color, including Marsha P. Johnson (Otoja Abit) and Sylvia Rivera, who becomes a “composite” character named Ray (Jonny Beauchamp).

If LGBT films today are framed by gay marriage, then the queer films of Haynes’s day, in the late ’80s and early ’90s, were defined by the AIDS crisis. The worlds of activism, art, experimental film, and cheap New York City rent collided to create a fertile time the film critic B. Ruby Rich named New Queer Cinema. New Queer Cinema had punch and swagger; it was acerbic, witty, subversive, and campy, spanning a vast range of aesthetics, genres, and histories, led by a group of filmmakers and artists that eventually included Haynes, Van Sant, Jennie Livingston, Isaac Julien, Sadie Benning, Marlon Riggs, Cheryl Dunye, and many others. Most importantly, they didn’t care about approval or acceptance. Film scholar Michele Aaron wrote that the defining feature of New Queer Cinema was an attitude of “defiance” — whether it was the HIV-positive cop-killers on the run in Gregg Araki’s The Living End or the homicidal couple that consecrates their self-sanctioned marriage by murdering a child in Tom Kalin’s Swoon, these were filmmakers who found liberation by embracing the margins. They were bold, sexy, dangerous, and depraved — radical in both content and form. Instead of running away from the accusation that queers were deviants, degenerates, and criminals, NQC films embraced it. When the Gay Liberation Front called out “Perverts of the world unite!” it was NQC that heard that call.

In fact, much of what made New Queer Cinema so transgressive is how it reimagined history in joyous, sometimes twisted ways. There are singing anuses in John Greyson’s musical Zero Patience, a historical corrective about Gaëtan Dugas, the Canadian flight attendant who had been vilified by the media and scientific community as “patient zero” of the AIDS crisis. Cheryl Dunye’s The Watermelon Woman created a fictional queer black actress named Fae Richards as a way to reimagine classic Hollywood. Derek Jarman’s exquisite Edward II, an adaptation of the Christopher Marlowe history play, makes King Edward II and Piers Gaveston’s relationship the central narrative. And Isaac Julien’s Looking for Langston (1989), a nonnarrative film about Langston Hughes, mixes archival footage with fiction to build a genealogy of queer black men beginning with the Harlem Renaissance, moving to James Baldwin and then the present. All of these films search in-between the lines of the historical record, for the people that history forgot. Even today, they ask: Who keeps the historical record?

It’s dismaying, then, to see that subversion erode over time. Perhaps portending its ultimate demise, Haynes’s Poison won the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival in 1991, while Jennie Livingston’s documentary about the Harlem ball scene, Paris Is Burning, won the documentary prize. Hollywood seized upon the burgeoning market for LGBT cinema (think Philadelphia and In & Out), and by 1999, New York Times described the films at the New York Lesbian and Gay Film Festival as “giddy gay lite.” What was once queer and fringe had been gentrified into something more easily categorizable, consumable, and thus marketable.

This isn’t to say that a queer sensibility — something subversive, punk, and anti-authoritarian — has vanished. Queerness, by nature, is hard to define, and equally hard to stamp out. There have certainly been queer films in the intervening years, including But I’m a Cheerleader and Hedwig and the Angry Inch. More recently, you can see it in BPM, Robin Campillo’s expansive film about ACT UP in the early ’90s in Paris, where love for community, and a symphony of voices arguing, protesting, and fucking fill the film; it’s in the liminality of Moonlight, where what often resonates are the things left unsaid; it’s in the wildness of The Ornithologist, the brashness of Xavier Dolan films, the claustrophobia of the aforementioned Duck Butter, and the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul and Cui Zi’en. You may notice that many of these weren’t made within the Hollywood machinery. And if this year’s Cannes Film Festival lineup is any indication, queer foreign films will continue to lead the charge, with the Kenyan coming-of-age story Rafiki, the Argentinian murder-twink film The Angel, and a slew of French films including Gaspar Noé’s dance-horror movie Climax, Sauvage, Knife + Heart, and Sorry Angel. Meanwhile, in America, coming up we have The Miseducation of Cameron Post (think a humorless But I’m a Cheerleader); Ideal Home, a comedy where Paul Rudd and Steve Coogan play a wealthy couple suddenly raising a kid; the Freddie Mercury biopic Bohemian Rhapsody starring Rami Malek that has already been accused of “hetwashing”; and a Love, Simon look-alike, Alex Strangelove.

Hollywood liberalism and the marketplace have converged to create an environment where being “the first” is confused with innovation, when actually, it’s just evidence that gay people can be commercially viable, too. While the AIDS crisis produced a rupture that galvanized art and activism, today we’re in a paradigm where a cadre of gay men and women are a part of the Establishment, and there is a greater compulsion to work within channels of power rather than outside of them. The era of gay marriage has created a profound complacency and misunderstanding that the biggest fight has been won; in fact, it’s only further obscured real and present dangers. In the U.S., there is still no robust, federal anti-discrimination law; there’s an alarming HIV epidemic among queer black people, homelessness, and ongoing violence against trans people. There is a pervasive sense that if you are not white and powerful, you will be left to die. We need to recover a cinematic language that captures the exigencies of queer American life, its skin and smoke, thickness and fragility. We need a queer cinema that thinks beyond the limits of commercial tribalism, beauty, and wealth, and toward new, imagined futures. We need a queer cinema that fights back.