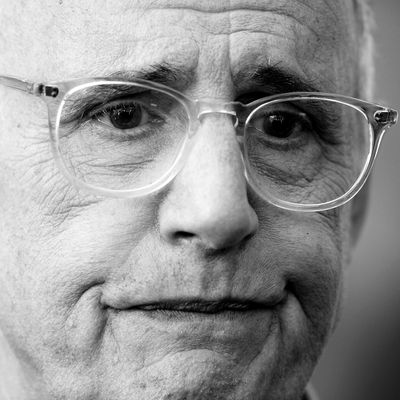

I interviewed Jeffrey Tambor on Tuesday, briefly, in a room with some of his fellow Arrested Development cast members, not including his co-star Jessica Walter. But it doesn’t matter what he told me.

It doesn’t matter because Tambor said almost the exact same word-for-word statement — presumably crafted with help from publicists, lawyers, or both — that he gave to the New York Times during their roundtable interview with the cast. This is the interview where Walter cried as she recounted Tambor’s verbal abuse on the set; co-star Alia Shawkat said that his behavior wasn’t “acceptable”; and fellow actors Will Arnett, Jason Bateman, and Tony Hale appeared determined to make it seem as if what he did was not that unusual, even as Walter herself insisted that it was more intense than anything she’d experienced in six decades of acting.

It also doesn’t matter because Tambor lost the power of illusion — the illusions he created with such painstaking care — and all you can see now are allegations that seem a lot more convincing than his vague apologies and promises to do better. Tambor is far from the first great popular artist something like this has happened to. He won’t be the last. And it’s not on us to either forgive him for it or try to factor it out as we watch his work.

That was never our job. It was part of his job. And he blew it.

I was thinking about all this en route to the interview. I love Arrested Development, but it’s yet another once-beloved work that I can no longer watch without cringing — not because of what happens within the fiction itself (cringe comedy of the highest order) but because one of the key people associated with it has been accused of heinous behavior. I can’t say that the show quite is on the “See No More” list alongside House of Cards or Woody Allen’s movies, because Kevin Spacey is in most of every House of Cards episode, and Woody Allen is responsible for every frame of a Woody Allen movie, whereas Tambor’s presence only becomes oppressive when he’s onscreen as George Bluth Sr. or his twin brother Oscar Bluth. But Tambor has just enough screen time to taint any goodwill you might feel for the work. I tried to rewatch season four — which I still think is a misunderstood masterpiece, possibly the first show of the streaming era that could not have existed on broadcast or cable TV — so that I could watch the recut version and compare them, but I had to stop after a couple of episodes because I kept looking at Tambor’s face and thinking of the abuse that three different people had publicly accused him of, on sets not unlike the one where creator and executive producer Mitchell Hurwitz & Co. make Arrested Development.

You know the sensation I’m talking about. You watch and laugh as Walter, Bateman, Shawkat, Michael Cera, and whoever else goof around and make jokes and pratfall, and then Tambor appears and suddenly all you can think about are the accusations of sexual harassment on the set of Transparent by his assistant Van Barnes, co-star Trace Lysette, and the allegation by makeup artist Tamara Delbridge that Tambor “forcibly kissed” her on the set of Never Again in 2001. And then you wonder if any of that also happened on the set of Arrested Development — and if so, which of the actors or crew Tambor inflicted it on, and which were complicit in normalizing it or covering it up. Poof, the spell is broken.

Walter talked specifically about Tambor’s verbal abuse during the Times interview, and was careful to say that she wasn’t aware of any sexual harassment happening on the set of Arrested Development (which doesn’t testify to anything except Walter’s own circumscribed experience, of course). “In like almost 60 years of working, I’ve never had anybody yell at me like that on a set. And it’s hard to deal with, but I’m over it now,” Walter told the Times. But verbal abuse isn’t something that can be shrugged off either. Not anymore.

All these decades, we’ve been conditioned to think that stinging verbal abuse, yelling, profanity, humiliation, is just a thing that happens in certain workplaces, Hollywood sets especially (see the indie comedy Swimming With Sharks, about a personal assistant’s abuse at the hands of a studio executive played by, erm, Kevin Spacey). In an interview I did late last November with Steven Soderbergh, he wondered if verbal abuse might be the next area of interest for #MeToo. “Any form of physical or sexual assault is a very serious matter, potentially a legal matter,” he said. “But I’m also wondering, what about having some kind of ‘extreme asshole’ clause? I know lots of people who have been abused verbally and psychologically. That’s traumatizing, too. What do we do with that?”

Good question. Everybody gets to answer it in their own way, and my answer is based on gut reaction: Once I know something like this, it makes it impossible for me to look at the actor and not think of the horrible things they’ve allegedly done. I don’t care to argue whether this is rational or not (I think it is), or whether I hold inconsistent opinions of works that are problematic for whatever reason (everyone does). The repulsed feeling is still there, and it makes a difference in how I react as a spectator.

Jeffrey Tambor is a great actor. He has brought his talent to bear on pantheon-level TV shows, stretching from Hill Street Blues and M*A*S*H through The Larry Sanders Show, Arrested Development, Transparent (not to mention films from And Justice for All… to The Death of Stalin). His performance as Hank Kingsley, the sidekick on The Larry Sanders Show, was one of the great portraits of showbiz narcissism, but I can’t imagine revisiting it with the same eyes now, especially during the season where Hank’s assistant, played by Scott Thompson, sues his boss for making homophobic jokes and contributing to a culture of harassment. I can’t lose myself in the fiction anymore because I don’t see the character he’s playing — not exclusively. I see the character for a few seconds or minutes at a time, and then the façade drops and I see the accused sexual harasser and verbal abuser who was fired from his award-winning lead role on Transparent, and who, according to Walter, verbally abused her on the set of Arrested Development.

This sort of thing seems categorically different from, say, watching a film starring an actor whose political beliefs are different from yours (though there, too, a line could be irrevocably crossed). Once you believe that a particular actor or filmmaker or screenwriter is a predator or abuser, you’re aware that the environment that produced your entertainment — the film set — was engaged in a conscious or reflexive cover-up, in the name of protecting an investment. You can still be passionately interested in the thing as a historical or aesthetic document — seeing it through the eyes of, say, an art historian who can contextualize Paul Gauguin within the totality of 19th-century painting, or an African-American studies professor who’s fascinated by Gone With the Wind — but you can’t lose yourself in it anymore. You can’t be in love with it. You can’t really enjoy it in the most basic sense, not without playing dumb.

You didn’t do that to the artist. The artist did that to himself.

And it’s awful. People’s lives get ruined, their careers get interrupted or destroyed. The emotional, physical, and financial damage that problematic artists inflict on people in their orbit should always be the first and main subject of discussion. Not only have actors reported all manner of sexual assault and harassment, many of them weren’t able to capitalize on their prime earning years because they were traumatized or blacklisted (or both). Rose McGowan, Annabella Sciorra, Ashley Judd, and Mira Sorvino are just a few of the survivors. As Rebecca Corry — a comedian who says C.K. asked if he could masturbate in front of her in 2005 — wrote in an essay published this morning, “I was put on an unspoken ‘list’ I never asked or wanted to be on. And being on that list has not made my work as a writer, actress, and comedian any easier.”

On top of all that, we also have the collateral damage of cultural vandalism. Fun, meaningful, even great works that dozens or hundreds of people labored over, that built careers and fortunes and whole industries, become emotionally contaminated to the point where you can’t watch them anymore. Forget the masterpieces that Jeffrey Tambor has been a part of. Louis C.K.’s show Louie helped pave the way for the “Comedy in Theory” genre that includes You’re the Worst, Atlanta, Better Things, Master of None (ahem, Aziz), High Maintenance, Insecure, and many other notable shows. Now, because of the indecent-exposure allegations by Corry and others — allegations C.K. himself confirmed as true — that series has become the Voldemort of recent TV: You dare not speak its name. Meanwhile, in recent years, an entire wing of African-American cultural history has been vaporized by the Bill Cosby allegations and his recent felony sexual-assault trial, including the most popular sitcom of the ’80s (The Cosby Show), some of the top-selling comedy albums of all time, the precursor to the R-rated buddy comedy genre (Uptown Saturday Night and its sequels), and the first Saturday morning cartoon with a predominantly black cast (Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids). Predators’ careers are getting raptured, as well they should be. But unfortunately — perhaps inevitably — their work is getting raptured along with it, imploding into dust as the culture moves on to things that aren’t as problematic (or that might have skeezy stuff going on behind the scenes that we don’t know about yet).

Nobody is stopping anyone from watching these works (though they’re no longer as easy to find, and you probably have to own a DVD player). We can still talk about them, study them, write about them, contextualize them. But the emotional connection has been severed. The work becomes archival. It loses its present-tense potency, something that significant or great works have always had the privilege of claiming in the past.

That’s all on the predators. It’s not on you. None of us asked for this.

As I wrote in articles about Woody Allen and Louis C.K., it’s not incumbent upon the audience to pretend not to know unpleasant facts about the performer so that they can enjoy fiction. It’s incumbent upon the artist never to put the audience in that position in the first place. It might sound like I’m describing one of those “morals clauses” in Old Hollywood contracts, but it’s a different thing, because it’s about protecting the audience’s emotional investment in the art, not just the studio’s investment in the product. It’s a basic courtesy, an implied part of the unwritten agreement that ought to exist between the artist and the viewer.

Certain things you can forgive or forget. Other things you can’t because they stain the mind. This is the misdemeanor on top of the crimes.

The room at the Essex had a strange energy when I entered it on Tuesday afternoon. Shawkat, Hale, Arnett, Tambor, and Bateman were there, but Walter wasn’t; she’d left the hotel about an hour earlier, right after the New York Times interview. I saw her in the lobby with her suitcase, walking toward the front entrance with co-star David Cross. A Netflix publicist later told me that Walter didn’t leave because of what happened at the Times interview — she got a last-minute guest spot on Bravo’s Watch What Happens Live and decided to do that instead, so it was apparently just a coincidence. I don’t really care one way or the other. What’s important is that four publicity people were sitting on the other side of the suite, maybe two meters away from where I was doing the interview, which only happens if the network is worried that the interview subjects are going to say something that will get them in trouble.

I was given 25 minutes. The five actors and I talked about craft for about 15 of them, then I asked Tambor, “Was the energy on set different at all because of your situation on Transparent?”

“That happened after we finished,” he said. “We were on the penultimate week of filming the series when the Transparent allegations came out.”

I asked all of the actors, “Was there any sort of discussion ahead of time about how to present the subject of these allegations when you’re sitting in a room together with somebody like me?”

“No, no, no,” Tambor said. “Netflix has been tremendously supportive, as has the cast. When I was invited, I sent an email to say, ‘I am so sorry for the distraction, and I so appreciate that you have to field these questions.’ I did an article with The Hollywood Reporter earlier, and I denied the allegations, and I’m no longer doing [the character of] Maura on Transparent. I’m going to miss her. I’m going to miss the cast very much. But I’m so proud to be here, and I think this is our best season. I’ve said it over and over again: These guys hit it out of the park,” he said, indicating his co-stars, “and I couldn’t be more proud to publicize that. I am honored to be among them.”

“Which of my bits was your favorite?” Arnett interjected, and everyone in the room laughed nervously.

“We have five more minutes,” one of the publicists in the corner said.

So does Arrested Development, I’d imagine. And that, unfortunately, is on Jeffrey Tambor.