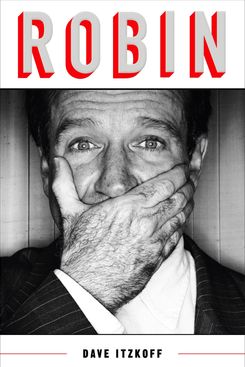

The following is an excerpt from journalist Dave Itzkoff’s new biography of comedian Robin Williams, Robin, out today.

In January 1982, Robin welcomed the latest celebrity visitor to the Mork & Mindy set: John Belushi, the husky, hell-raising star of Saturday Night Live, The Blues Brothers, and Animal House. Belushi had been talking to Paramount executives about a new film project, and in his downtime he dropped by Stage 27 to watch Jonathan Winters ad-lib a scene about a World War II veteran who realizes the Japanese soldiers who shot at him at Okinawa are now tending his garden back in America.

Belushi had hung out with Robin a few previous times in New York, where Robin sang backup to his peerless Joe Cocker impersonation at Catch a Rising Star, and Belushi took him on a tour of the city’s punk rock clubs. Robin said the experience was “like being on a tour with Dante, if Dante were James Brown. I was like Beaver Cleaver in the underworld.” When Belushi was in Los Angeles, the two of them sometimes got their drugs from some of the same people.

On this visit, Robin was mourning the loss of Harvey Lembeck, the influential Los Angeles improvisation teacher who had helped him find his way to sitcom stardom, and who had died of a heart attack after falling ill on the Mork & Mindy set, where he’d been filming a role. Robin was still hurting, too, from his experience with Popeye, racked with self-loathing about the declining fortunes of Mork & Mindy and questioning whether he was anything more than a one-hit wonder. Even a throwaway item in a local magazine’s In and Out column, which decreed that being at a party attended by Robin Williams was henceforth Out, had gotten under his skin. He thought frequently of the giant billboards and posters along Sunset Boulevard that advertised the hot new movies and albums, which elevated the stars featured in them to the status of gods. But Robin had never been depicted in one of these promotions, and it ate at him. “They’re fifty feet tall and I’m only five foot eight,” he thought. “I’m nothing.”

Robin was lifted out of his funk when he watched Belushi observe Winters on the set; Belushi’s quiet admiration for this legendary comedian seemed pure and sincere, to the point where he would shush anyone who tried to talk to him while Winters was playing his scene. Robin and Belushi did not say much more that day, but they made vague plans to see each other again soon.

On the night of March 4, Belushi was staying in Bungalow 3 at the Chateau Marmont, the shadowy gothic hotel that loomed over the Sunset Strip, while he continued to negotiate with Paramount about his next film project. Around midnight, Belushi ran into Robert De Niro and Harry Dean Stanton at On the Rox, an elite nightclub above the Roxy Theatre, and at two A.M. Robin, having wrapped up another therapeutic early-morning set at the Comedy Store, came by to find that the club had just closed. A bouncer told him that De Niro and Belushi had been looking for him, so Robin drove over to the Chateau. At the hotel, Robin first phoned De Niro, who told him he couldn’t make it down from his room. So he headed over to Belushi’s bungalow, where he was let in by Derf Scratch, the bassist from the punk band Fear, and waited for its primary resident to return.

When Belushi came back, he was joined by Cathy Evelyn Smith, a singer and drug dealer who had dated musicians like Levon Helm and Gordon Lightfoot, and her presence made Robin deeply uncomfortable. She seemed gaunt and worn down, and the room itself was disheveled and strewn with empty wine bottles. Belushi took out a guitar and strummed a few chords; subsequent accounts of the evening would later state that he and Robin did some cocaine, though Robin himself denied this.

As Belushi grew groggier — he said he’d taken some quaaludes earlier — Robin realized it was time to go. He told Belushi he was welcome to visit him at his new ranch in Napa Valley, then he made the drive alone to his home in Topanga Canyon, where Valerie was waiting for him. He told her that he’d just been to see Belushi but could not put the image of Cathy Evelyn Smith out of his mind. “God, man,” he told Valerie. “He was with this lady — she was tough, scary.”

Sometime later that morning, Smith prepared two speedballs — powerful mixtures of cocaine and heroin — injecting herself with one and Belushi with the other. He complained of feeling cold, so she turned up the thermostat and tucked him into bed, where he fell asleep. In his sleep, he died of an overdose, from the toxic quantity and combination of drugs he had taken. His physical trainer discovered his lifeless body just after twelve noon. He was thirty-three years old.

That morning, Robin had come to work a little late and a little bleary, as usual, and he told Dawber about his unusual night. “He said, ‘Wow, I was with Belushi last night, and boy,’” Dawber recalled. “First of all, Robin never had judgment, because he was doing a lot of the same stuff, but certainly not what Belushi was doing.” He recounted for her his missed connection with De Niro, his uneasy visit to the bungalow, and how magnificently Belushi had played his guitar, as stoned as he was. “‘He could hardly stand up, and yet he could play the guitar to perfection,’ — that’s what he was saying,” Dawber said. “There was some girl there and John was just so stoned. That’s what Robin told me about that, and I went, ‘Wow. Okay.’”

Just as the cast and crew were preparing to break for lunch, they received the news that had been rippling across Hollywood that day: Belushi had died in his bungalow at the Chateau. The producers knew that someone had to tell Robin, but fearing that the information would devastate him, they felt that it was best delivered by a trusted friend like Dawber. “They said, ‘Will you tell Robin?’” she recalled. “I said, ‘Oh, God, Robin was with him last night.’ And they said they knew. I don’t know how they knew.”

Dawber waited for a discreet moment when she and Robin were walking back from the Paramount commissary: “I said, ‘I’ve got something really terrible to tell you, Robin. He went, ‘What? What?’ And I said that John Belushi was found dead last night.” Robin found it incomprehensible to hear this about someone he had seen only a few hours earlier. “He went, ‘What? I was with him last night! I was with him last night!’” Dawber said. She could see that Robin was in pain but wanted to make sure he did not ignore the larger lesson in all of this. “I said, ‘Robin, if that ever happens to you, I will find you and kill you first.’”

By now, she and Robin had made their way back to Stage 27, and they could hear the growing clamor of the studio audience being let in for the taping of that night’s show. Dawber started looking for her script when she saw Robin standing with his hands cupped over his crotch, which for him was a sign of pensive contemplation. He was looking down at the ground, still processing the ultimatum that she had just given him. In a soft, solemn voice, he answered, “That’s never going to happen to me, Dawbs.”

As he grieved for a friend who could have had decades of great work ahead of him, Robin did not need any assistance to see how Belushi’s death communicated an unmistakable message, addressed directly to him and all but hand-delivered to his doorstep.

Robin later described Belushi as “a powerful personality and a powerful physical being, too. When someone like him takes the cab, it wises your ass up really quick… . John was on the frontier; he was out there pushing it.” After his death, Robin said he could not help but look at himself and realize that a drastic change of lifestyle was needed if he wanted to avoid the same destiny: “It was like, ‘Look at you, you little frail motherfucker. You’re small change, Jack.’”

Excerpted from ROBIN, by Dave Itzkoff. Published by arrangement with Henry Holt and Company, May 15, 2018. Copyright © 2018 by Dave Itzkoff. All rights reserved.