In an age of great advances in the art of opening credits, Upgrade gets points for ingenuity. Over an array of reverberating lines of sound waves, the names of the various production companies are recited in a chilly, Siri-like feminine AI voice — no text or flashy typefaces to be found. The effect is absolutely startling, and has you wondering for a split second if the descriptive text service accidentally got turned on on Netflix. Which is to say that, before seeing a single filmed image, Upgrade already has you thinking about digital assistants going rogue.

Despite that austere opening, Upgrade, written and directed by horror impresario Leigh Whannell, is a great and grimy little screw-turner of sci-fi schlock, the kind that they truly don’t make anymore, the kind that would make Carpenter and Cameron proud. Black Mirror will surely get thrown around as a comparison point, but Upgrade is purposefully more visceral (literally, abundant with viscera) and action oriented than a latter-day Twilight Zone. More importantly, its logical leaps are not in service of a more twisted and dark future vision, but rather, fun.

Logan Marshall-Green is Grey, a muscly man living an unspecified number of years in the future, who we find fixing up a muscle car while listening to vinyl. He’s the type of sci-fi character whose increasingly anachronistic resistance to the automated age he’s living in will inevitably make him the perfect mark for someone’s dark scheme. His wife Asha (Melanie Vallejo), meanwhile, rolls up to their future house in her armadillo-like self-driving car, tsk-tsking the motor oil smeared on her husband’s skin-tight white tee. Somehow, these two crazy kids make it work.

But after dropping off his latest job at the underground not-at-all-villain lair of baby-faced tech mogul Eron Keen (Harrison Gilbertson), they let the AI take the wheel in order to have some smart-car sex, and things quickly go downhill. After what might be the first truly distressing self-driving car horror sequence — sweat-inducing enough to drop Tesla’s stock by a decimal point or two — Asha is murdered before Grey’s eyes, and he wakes up a quadriplegic, wheelchair-bound and single-mindedly determined to bring her killers to justice. Help arrives in the form of STEM, an implant designed by Eron, which restores the connection between Grey’s brain and his body — with a commentary track. Grey is able to walk again, albeit with a kind of automated, Terminator-lite stiffness (gears whir subtly on the soundtrack as he tries out his new OS) but he’s also host to STEM’s AI, which offers advice and observations, and, on request, can take over control of Grey’s body to execute lightning-fast martial-arts moves. Meanwhile, the cop on his wife’s murder case (Get Out’s Betty Gabriel) starts to sense that something is up with her bereaved husband.

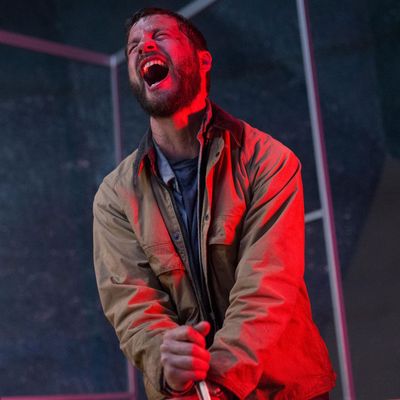

Upgrade exists for those fight scenes — not only for their chop-socky glory, but for the subsequent horror and delight and guilt on Marshall-Green’s face as STEM eviscerates his enemies for him. STEM is part HAL, part the tuxedo in the Jackie Chan vehicle The Tuxedo, as bracing and deeply silly as that combination implies. Whannel’s film is ultimately about heightening the kind of outsourcing of busywork we do every day to vengeance-murder extremes, and the sneakily underrated Marshall-Green is great at conveying the increasing alienation between Grey and his body, playing the absurd physical humor and horror equally well. At one point, STEM has Grey “print out” a piece of evidence with a pen and paper; Grey’s hand skitters across the sheet like an old-school ink-jet and Marshall-Green’s aghast, powerless witnessing of it had me shrieking with laughter.

Why is it so cathartic — and hilarious on a bone-deep level — to see this kind of horror expressed? It’s easy to see ourselves in this helpless futureman, who all too often calls on his inner robot butler for assistance, quick to forget the last time he did so and deeply regretted it. It’s funny the same way it’s funny to watch anyone foolishly indulge in a vice; it’s basic, eternal, humanoid folly, whether it’s Cookie Monster stuffing his face or Grey struggling to look away as he dislodges the top and bottom half of a goon’s face. The final reveal of the true nature of STEM and its creator is less interesting than the basic man vs. machine farce that Whannell executes so briskly. Likewise, Upgrade is serviceable as a speculative narrative, but even better as a physical one.