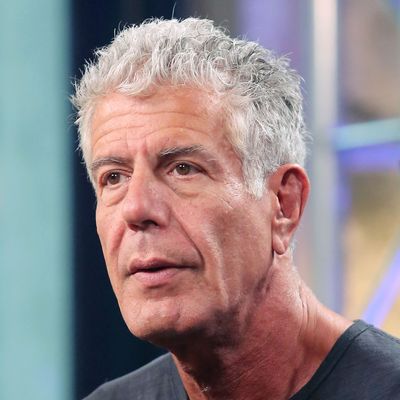

I don’t have many regrets, but if I could have one do-over, I’d cook for Tony Bourdain. It was Bourdain who wrote, I think, that chefs love it when others cook for them. But no one ever wants to because they’re, well, chefs.

Bourdain passed through New Orleans in the fall of 2010. He was one of the writers for Treme, a show created by my husband, David Simon, and Eric Overmyer. But his participation in the show was the result of a ruse I had set in motion a year earlier, when David, drunk on a No Reservations marathon, had wondered aloud how they might meet. They were destined to be friends, he just knew it. But how to connect?

I told him he should ask New Yorker editor David Remnick to share Bourdain’s contact information. After all, Bourdain’s success had started there, with the article that became the springboard for Kitchen Confidential, and my husband had owed Remnick an article for years. Besides, we had met Bourdain in passing in Manchester, England, in 2000, at a crime writers’ conference known as Dead on Deansgate. David had no shortage of material to work with.

A day or two later, I came home to find David pacing worriedly. Remnick had given him Bourdain’s phone number. A phone number! What could he do with that? He had hoped for an email, which would allow him to dazzle Bourdain with his wit and wordplay.

I coached him as a helicopter mom might coach a teenage son asking for a first date. He’s a chef, I said. You’ve got a chef character in this New Orleans show you’ve sold. Call him and say you need to pick his mind. Oh, and there’s one condition: I’m going with you.

Three months later, David and I met Bourdain at a Midtown sushi restaurant in New York. We were so committed to the bit that I brought a Moleskine notebook and jotted things down from time to time, a thoughtful frown on my face. (Only for a chance to meet Bourdain would I pretend to take on secretarial duties for my husband.) David was so nervous that he poured sake on his sushi. Later, he was full of self-recrimination because he used soy sauce and Bourdain did not. How could he be such a rube?

But, by meal’s end, it was obvious that the lie had to become true. David needed Bourdain to get kitchens right. He also needed Bourdain to recruit other chefs. Tom Colicchio, Eric Ripert, Wylie Dufresne, and David Chang would all come to New Orleans for cameos on Treme, thanks to Bourdain.

Heeding Bourdain’s advice, I should have cooked for all of them. But I wish, in particular, that I had cooked for him. Bourdain understood that the food we make for ourselves is just another way of telling the story of our life. My family is southern, with everything that entails from the worst to the best. Living in New Orleans, as I did for five years starting in 2009, I reconnected to that part of myself.

What would I have cooked for Bourdain? Fried chicken, served cold; fried okra; homemade pimento cheese; cornbread; potato salad; blistered shishito peppers (the New Orleans farmers market often had them); and a Coca-Cola fudge cake, an easy, beloved recipe that would have allowed me to talk about my late-in-life epiphany that I really was a southerner, if only because I have two Uncle Bubbas. I would have shown him my mother’s cornbread pan, which baked the batter into little ears of corn, and asked him earnestly if he liked cornbread with or without sugar.

Instead, we took him to August, a lovely restaurant and a then-favorite of mine, although I haven’t been back since Brett Anderson’s exposé of owner John Besh. Our daughter was about 6 months at the time and Bourdain asked to hold her for part of the meal. His daughter was 3, he told us. He missed the feel of a baby in his arms.

So I have that image: my daughter, sleeping peacefully in Bourdain’s lap. But we should have dared to invite him into our home, to feed him the food we make for ourselves. I imagine him staying late into the night, smoking and drinking on our side porch, talking with David about Henry Kissinger, whom they both reviled. I’d tell him how my mother, living in “Yankee” Maryland, had to sweet-talk the truck farmers into growing okra just for her. That I had grown up in a house where collard greens and black-eyed peas were staples — and that I had loathed them until I was an adult.

The writer Martin Amis once told me in an interview that it’s natural to yearn for another writer’s approval and friendship; he had pursued Saul Bellow and John Updike for just that reason. “It’s a kind of communion,” he said. Bourdain sought out many writers I know — Stewart O’Nan, George Pelecanos, Ian Rankin, Daniel Woodrell — and asked them to help him define their hometowns by way of food. To my knowledge, he never read a word I wrote and I know I would never be his chosen guide no matter how many times he visited Baltimore.

But I “wrote” the script that brought him into my husband’s life and that’s good enough for me.