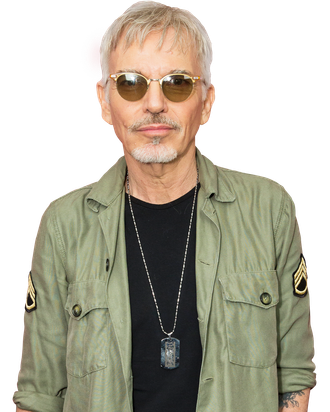

Billy Bob Thornton has taken home two Golden Globes and one Oscar during his nearly 40-year career as a writer, director, actor, and musician, but even his fans might have trouble naming all three of the projects he’s won for. The Academy Award came for writing Sling Blade, the 1996 southern gothic character study that Thornton also starred in and directed, boosting himself onto the Hollywood A-list after a decade of toiling in relative obscurity. The Globes, meanwhile, have honored two recent prestige television roles. Thornton’s turn as the ice-cold killer Lorne Malvo in the first season of Fargo is the one that’s more remembered, though he’s doing some of his best-ever work with his other award-winning character: the alcoholic washout lawyer Billy McBride, in Amazon’s moody, underrated L.A. mystery series Goliath.

Goliath returns this Friday for a second season that sees McBride struggling to build on the big moment of personal and professional redemption that ended season one, but also taking on a new case that plunges him into a good old-fashioned L.A. power-broker conspiracy. Behind the scenes, series co-creators David E. Kelley and Jonathan Shapiro passed the baton to a new showrunner, Clyde Phillips (Dexter), who was replaced during production by executive producer Lawrence Trilling. Ahead of the season premiere, Thornton spoke with Vulture about the rewards of playing the same character for 16 hours of TV, as well how his southern upbringing informs both his thriving music career and his dormant — for now — writing and directing.

With Clyde Phillips and then Lawrence Trilling running Goliath, did you find the experience of making the show to be different?

Not terribly. Larry Trilling, who was on the first season as a producer and director, was with us this season, too. So he’s sort of a through line, y’know? Larry’s the guy I talk to on a daily basis about the show. It’s good to have people you’re real familiar with around. He gets the show, inside and out. He really works hard at it, and he knows the vibe. You don’t have to explain much to Larry.

Season one felt more like film noir than a courtroom drama, and now with all the L.A. politics entering the picture, season two is even more like something from Raymond Chandler, Michael Connelly, or Ross Macdonald.

That’s absolutely true. People have said that this character started out a little like Paul Newman in The Verdict, and now this season’s like if you add Paul Newman in Harper. I’m out there getting up into all kinds of hijinks outside the courtroom. If anything, this year has even more of a noir feel.

Do you have any favorites from that genre, either novels or movies?

I’m a big fan of the whole noir period. I like all the usual ones. The Bogart movies really thrill me. You know the old story of The Big Sleep? They say The Big Sleep is a movie that nobody knows what it’s about, but it’s still really interesting. Which is very true. There’s something about that genre that just draws you in and puts you in a mood. There’s just something vibe-ier about black-and-white.

If you can make a color show or movie seem like it’s in black-and-white, then you’ve done a really good job. That’s kind of what we do.

Is there are a lot of research involved with the legal side of playing Billy McBride?

We had the great fortune of having David Kelley and Jonathan Shapiro on the set a lot in the first season. They’re lawyers. For this new season, we had a technical adviser. And it’s not like I haven’t had a divorce or two, so I’ve been in court. I also have a couple of friends who are pretty big attorneys — just pals of mine, not people I’ve worked with, fortunately.

I ask questions. I want to make sure that I’m getting that part of it right, and that I’m not doing anything that would be atypical of a lawyer. Like, one thing you see in a lot of law shows or movies, a lawyer always goes right up to a witness on the stand and they shake their finger in their face and they walk around the chair where they’re sitting. Y’know, you don’t really do that. [Laughs.]

Whenever there’s a bunch of technical lawyer jargon, I ask what it means. Because when you’re playing a character, you don’t want it to sound memorized. You want know what you’re talking about. Same thing in Armageddon — I talked to NASA guys to find out exactly what all this NASA stuff I was saying meant, so it didn’t sound like I was saying it by rote. Pushing Tin, I went to air traffic control school in Toronto for that. Passed with flying colors, by the way. If I ever become an air traffic controller and I’m the guy in charge of your plane, you’re in good hands.

You’ve been a regular on three television series. In Hearts Afire you were doing more broad comedy, and in the first season of Fargo, your character was muted by design. But Billy McBride seems more like the kind of characters you usually play in movies. More nuanced.

I love independent film so much, and that’s kind of where I made my mark. But independent film is not as big a thing now. The type of independent film I made is out of existence, so doing something like this gives me an opportunity to do an independent film over a long period of time. That’s exactly what it feels like. It doesn’t feel like television in the traditional sense.

Y’know, all the independent films that I did, that I loved, I never wanted ’em to end. I wanted to keep playing that character. In this case, I get to do that. And it only helps because I’m settled into this guy. I feel like I am him, at this point. It absolutely gives you a little extra confidence, because you know that you don’t have to hurry things up to get across to people the vibe of this guy and his world.

Given what that character goes through, saying that you relate to him might not be the best thing.

[Laughs.] Well… I’ve got my demons, but not as many as this guy.

It must help to build a character when you’re acting opposite the likes of William Hurt, Molly Parker, and Maria Bello.

Oh sure. It’s different from how things are in music, for sure. Let’s say you’re in some hot band, and you’ve got an opening act on your tour that’s astoundingly good. In music, you don’t want somebody coming out there for 45 minutes and blowing the doors off and then you’ve got to come out and follow it up. In acting, it’s exactly the opposite. If you’re a good actor and you know a scene inside and out, you’ve got your character down, and if you’re working with people who don’t have that, you’re gonna suffer. The more good people around you, the better off you are.

Did you have anything to do with Dwight Yoakam being cast in season one as a shady CEO? The chemistry you guys have together really pays off in the season-one finale, where you finally get his character to admit some guilt.

Well, everybody’s aware that Dwight and I are best buds. It wasn’t like I came to ’em and said, “Hey, put Dwight Yoakam in here.” It was more like they came to me and said, “Hey, do you think Dwight would play a part in this?” and I said, “I’m sure he will, I’ll call him.” Y’know, when you’re working with a buddy, it’s easy to get that same vibe you have when you’re together in real life. In a drama, when it’s just a couple of folks who know each other, talking things over, it can be pretty seamless.

It’s harder when you’re doing a comedy. If you’re in scenes with a guy you know really well in a comedy, you tend to crack each other up too much. John Ritter on Sling Blade, y’know John and I were friends already, and when he would see me as that character, at first he couldn’t hold himself together. Of course he finally did, and did an amazing job.

It’s a shame that you say there’s not much room for the kinds of movies you like to write and direct, because Sling Blade, Daddy & Them, and Jayne Mansfield’s Car have a real feel for the complexity of the South that’s missing from a lot of other films.

Well, I do have plenty to say. I’ve got plenty of other movies I could do, just like those. I don’t know how relevant they are. Maybe I’m obsolete at this point as a writer-director. I mean, Jayne Mansfield’s Car, nobody saw it, and the people that did didn’t get it or just didn’t like it. I think if I’d made that movie the year after Sling Blade, it would’ve been a very viable commodity. These days? I don’t think so.

I like to mix dark humor and drama, and for some reason these days things are very compartmentalized. A lot of independent films, they either make something so weird that it’s inaccessible, or they make it squeaky clean so that it just scratches the surface of some heavy subject. It’s not that I don’t want to make another movie, or that I don’t have more to say, it’s that I just don’t know if the audience, or the studios, or the financial backers have any interest in hearing my stories. Because most of my stuff is based on southern literature and my experiences and … I dunno.

I mean, it would be great if I could make a movie for just 25 people. [Laughs.] But it’s hard to find anybody to give you money for that.

Who else do you think has gotten the South right in movies?

I don’t know of any recently because I haven’t seen many, but y’know, The Last Picture Show really captured a little Texas town very well. I believe that Coal Miner’s Daughter, which was done by an Englishman, Michael Apted, I think he really got the Loretta Lynn story down really well.

I think the only flaw in that movie is that Loretta Lynn still had a career and was a vibrant woman. Most biopics, y’know, they die in an airplane crash or whatever. Like Buddy Holly. The Loretta Lynn movie for the last 15 minutes or so had nothing to say. It’s like, well, she’s still going. [Laughs.] But up until that point, it was brilliant.

I’ve seen a lot of movies about the South made by people who aren’t from the South that don’t particularly pay much attention to the actors they cast. My standard joke is if you’re making a movie about Charles de Gaulle, get a Frenchman, not me. But if you’re making a movie about Texas, don’t get a Frenchman. We’ve got plenty of Texans. You need to cast people who can pull it off. I’ve seen actors from the Bronx do southern parts, and it’s not always good.

The flip side is, you don’t see a lot of southern actors doing people from the Bronx. For some reason, it’s not a two-way street.

The other day I was watching a Classic Albums episode about Frank Zappa, for which you were interviewed, and it reminded me of the scene in Jayne Mansfield’s Car where your character talks about liking “underground music” because “it’s real different.” That’s something I think other filmmakers miss when they tackle the south, that it’s not one monolithic thing. Arkansas alone contains both down-home country boys and Zappa fanatics.

Well, y’know, Zappa was a huge influence on me. The early Mothers of Invention showed me that mixing humor and music and all those things together was possible. It’s one of the reasons I left home, honestly. I heard the Mothers and was like, “Hey, there’s a lot going on out there.” There weren’t a lot of 11- or 12-year-olds listening to the Mothers or Captain Beefheart or the Bonzo Dog Band back where I was when I was a kid. It just made me think, “I guess I’m kind of different than the people I’m growing up around, maybe I should go somewhere else.” I talked to Jim Jarmusch about that and he said that’s why he left Ohio, too.

I used to go into Paula’s Record Shop, back when towns only had the one little record shop and it wasn’t some corporate thing. I didn’t always have money to buy the records. I’d just go in and stare at the album jackets, read every bit and look at the pictures. The first time I became aware of Frank, I actually couldn’t afford the record, but I was really interested, just looking at cover. Then this kid named David Jones moved from Connecticut to this little hillbilly town of ours, and he had the record and played it for me. “Call Any Vegetable.” That was my kind of song.

I went on to play music around Arkansas, and I roadied a few shows. I did Pure Prairie League. Remember B.W. Stevenson, the guy that did “My Maria?” And I think maybe Ozark Mountain Daredevils, or somebody like that.

These days, do you think of yourself primarily as a musician or an actor?

I just consider myself an artist. It’s all the same to me. It’s all just a different facet of whoever you are, creatively.

I’m going out in July and August [with his band, the Boxmasters], for two whole months. We just finished two new records, too. We’re developing a much bigger following, and the tours are becoming profitable. I think we’re really coming into our own as a recording band. When a band’s together as long as we’ve been together, 12 years now, you really start to settle in. So that’s going well.

And I’ve never enjoyed acting more than I do right now. I love playing this character.

This interview has been edited and condensed.