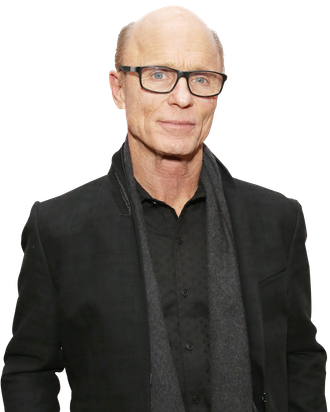

Ed Harris has enough iconic characters in his 40-year career to make other actors jealous — and that was before he added Westworld’s Man in Black to his repertoire. We’ve learned more about Harris’s character, the ultimate player of the game, in season two of HBO’s epic drama as he has progressed deeper into the park amid a robot uprising. In Sunday’s episode “Vanishing Point,” Westworld reveals the most traumatic moment of William’s life — the suicide of his wife, Juliet (Sela Ward) — and pushes him to the absolute edge of cruelty and sanity: After shooting his own daughter, Emily (Katja Herbers), he’s last seen slicing open his arm to see if he’s actually human. Ahead of the episode, Vulture spoke with Harris about “Vanishing Point,” why he’d never want to direct an episode of Westworld, what he thinks of the show’s fandom, and why he loves Atlanta.

Westworld is a famously secretive show. How much of William’s arc do you know in advance? And how does that affect the way you play the character?

The first season was different than the second season. The first season was full of surprises as to what was revealed to almost all of us every episode. We found out things in like episode five, six, and seven and were like, “Wow, that’s news.” The second year, I knew the path that my character was on and where I was headed.

How is this project different from others you’ve worked on?

I’ve never really done this kind of episodic series, so that’s different unto itself. And the length of the season is pretty long. The first year was ridiculous. We stopped and started again — six, seven, eight months. You work two, three days a week max, some weeks you don’t work at all. And this particular show is so complicated. There’s so much being shot. The end of the second year, they had three or four crews working on different episodes. I’m glad I’m not the person trying to keep track of it all.

When even the writers aren’t sure of the backstory, how does that change your approach?

Even when they are sure, they don’t tell you. [Laughs.] I would say, “Hey, look, I just did 125 performances of a play in London. I knew what was going to happen every night. And I was still very present and fresh. You can let me know whatever you want to.” What I didn’t know, I didn’t know. I was going episode by episode, particularly scenes, characters, who I was working with, and what was going on. I didn’t really fret about what I didn’t know because I didn’t know what I didn’t know.

More in the moment.

Very much so. For me, anyway. I took it a script at a time, scene at a time, line at a time. Be present and real and tell the truth.

What’s the most challenging part of this role?

In terms of where it’s going, I guess the difficult thing is just gauging that and trying to understand it. For instance, the episode Lisa [Joy] directed, episode four, she was great to work with because she knew more about [William’s] intent than I did. She was very helpful, in terms of “this is what’s going on inside of him now and this is where it will lead.” When you play a character, you try to get as deep in there as possible. When certain things are revealed to you, it’s very helpful.

How much of the buzz around the show do you pay attention to? The fandom is pretty vocal.

Absolutely none. My wife, who’s a news junkie, will say, “Ed, they’re writing about blah blah blah,” and I’ll say great. I’m very happy it’s a successful show and I love working with the directors and the cast, but I don’t really pay attention to all of the guesswork and what people are trying to figure out.

Is this true across your career? Do you read your reviews?

I really don’t. I remember things that were said to me when I was 28 doing theater in L.A. that I don’t need to have in my head, you know what I mean? If you’re doing a play today in New York, you can’t help but find out if it was positive or negative.

Did you discuss the character at all with Jimmi Simpson? Compare notes?

A little bit. We have a good relationship. I said, “Anything I can help you with, let me know.” He would email me some questions every once in a while, but I didn’t even know there was a younger me until I saw a guy walking around the trailers and said, “Who’s he?” “That’s you.” “Oh. Really? Thanks for telling me.” I think Jimmi does a great job establishing the whole history of this guy.

What did Sela Ward and Katja Herbers bring to “Vanishing Point” that made the episode different?

It’s nice to be out of the Man in Black suit and just be William, the family man, however poor he is at it. Sela was brand-new to the whole situation, so you just try to make somebody like that as comfortable as possible. Work with them. Have them welcome. Get rid of whatever nerves they have. Katja is great. She’s not afraid to ask me things, acting questions. I love talking about it. If she has something that’s bugging her or is stuck in something, we can discuss it.

The episode is about obsession, especially the kind that can blind us from what really matters. Have you ever been obsessed?

I was definitely obsessed with Pollock in the ‘90s, but it was a good obsession. I wasn’t blinded by anything. Let’s see. I like to get into things. I like to do things well. I can get pretty easily obsessed with something I care about, but not necessarily blindly.

Do you have any character or story input on Westworld?

Hmm, we probably had some discussions. Never any major points of disagreements. I did say in one public forum, “I don’t want to be in a samurai suit and I don’t want to be naked.” There are two things I suggested.

How do you pick parts at this point in your career? What’s important to you?

What’s important to me at the moment, which I will know in the next few days, is if I can get financing for this film I want to direct in August or September. It’s a Montana novel called The Ploughman — Robert Duvall, Garrett Hedlund, my wife Amy [Madigan], my daughter [Lily Dolores Harris]. I wrote the screenplay and I’ve been fighting to get the money I need. If I don’t, we won’t be able to make it for a while.

Why is that so important?

Well, I’ve only directed two movies and I haven’t directed in ten years. I really love doing it, and this is a novel that I think could make a really cool movie. I adapted it a couple years and I’ve been trying to do it for the last three years. I really, really, really want to do it.

It sounds like a big, challenging project. When you’ve accomplished so much, are you still looking for things that challenge you?

Yeah, definitely. I just did this play in New York, Good for Otto, the new David Rabe play with my wife Amy. And it was definitely a challenge. A 14-character play. Every night, you’re out there and you’re trying to make it work. I still really enjoy what I do. The acting part of it is more fulfilling in theater than in film work, in a certain way. One of the things I love about directing is you’re constantly focused. You’re constantly occupied. For instance, in Westworld, I’m on set two days a week, and then I may not work for two weeks. I may not know I’m not working for two weeks because they don’t know yet. You’re on set for 12 hours and on camera for ten minutes. It gets a little bit old after a while. You try to keep a good attitude.

Would you consider directing an episode of Westworld?

Jon [Nolan] and Lisa mentioned it to me a while back, but I don’t think I’d be a good director for Westworld because I have a hard time understanding it. [Laughs.] I’m as confused as anybody else watching this thing. I don’t always know what’s going on.

Do you watch your past work? If The Rock is on cable, do you watch it?

If I’m flipping and I happen to see it, I might watch it for a little while. Just for fun. I won’t hunt it out to see something that I did.

What’s your airport question? What do people recognize you for and what do they ask you when they do?

It’s a wide variety. Sometimes people come up and say something like, “Milk Money is my favorite movie.” “All right, I’m glad you enjoyed it.” [Laughs.] A lot of guys go “The Rock! The Rock!” Or I’ll hear, “I really liked you in The Hours.” “Pollock is my favorite movie.” Now Westworld. More people have probably seen that than all the films I’ve ever made. It’s a little bit strange, but it’s alright. You get used to it. I kind of skulk around. I don’t ask to be recognized. I’m always wearing a hat and glasses. I don’t mind if people are polite about it.

You’ve been acting for 40 years. How do you think film and television have changed?

You’ve got, what, 500 scripted shows? I was talking to Amy the other day, and we get all these Emmy screeners in the mail, how could anybody possibly watch all of this stuff? They should have categories. Emmys for HBO. Emmys for network. Emmys for Hulu. That’s the main thing that’s changed — the amount of stuff being put out there is amazing. And in film, it’s all tentpole business. You go to a ten-movie theater and eight of ‘em cost $200 million to make. It’s very different.

So, how do you find what’s good through all the clutter?

There are a lot of good things. I was watching Atlanta last night and I just think the originality of that show is beautiful. You never know what’s gonna happen week to week. It’s so quirky and fun. It’s cool. That’s one of the good things. There are a lot of really good things written, produced, and directed that would never be done in film.

Do you think TV is at a more creative point in its history than film?

You know, there are so many independent films being made that you don’t even know about, I can’t really say. I think there’s a lot of wonderful, creative work being done. I go out the Sundance Film Lab every June if I’m not working. They’re very creative. They’re wonderful.

What’s next? Hopefully the Montana film, right?

If it doesn’t happen, I don’t know what I’ll do. I’ll keep working outside in my yard.

Is that what you like to do?

Yeah, I got some acreage. That’s what I like. Be outside. Close my mind.