Photo: Sony Pictures/Everett Collection. Colorization by Gluekit.

We shot Waiting for Guffman in Austin, and after the first day of shooting, we all piled into a van to go back to the hotel. I lay down in the backseat and pulled my knees to my chest, telling everyone my back hurt. “That’s from holding in laughter,” Eugene Levy said, sounding “old hat,” like a vaudevillian actor. I took a bath that night and cried from the shock of the day. It was strange improvising — like, Really, this is going to work? I couldn’t remember what I even said that day.

Most films have a script, with the character’s dialogue written for them. Actors learn the lines and figure out the subtext, what’s “under” the line. Nowadays, though, most screenwriters don’t write like that; the style has become more literal and the dialogue constructed to serve the plot. When a movie is unscripted, the character lives without the lines of the material and this allows for real things to happen in the moment and be caught on film.

Chris says, when directing, “Don’t feel like you have to say anything.” And, “You can take your time and have space between your thoughts.” He exudes this in real life, too. He’s Zen. I mean, Jesus, he’s a lord. His full name, to be properly Anglo-Saxon about it, is Lord Christopher Haden-Guest.

For his movies, the actors are given an approximately 30-page outline, describing what happens in each of the scenes — different “beats” to hit. I was young, like 25, when we shot Guffman, and excited to work. This Is Spinal Tap didn’t impress me since I didn’t like heavy-metal music, so I wasn’t intimidated by Chris or the process. We were all pretty nervous about our audition scenes, though, for the musical within the film, called Red, White & Blaine.

The auditions were held in the high school. Bob Balaban had just arrived to play the musical director, as well as one of the judges. I’d never met him. I knew him from Close Encounters of the Third Kind, and he seemed very serious and intimidating. Bob Odenkirk had come to Austin for a few days to play the priest, and now he was pacing the hallways in theatrical vampire makeup, with contour makeup on his cheekbones and lipstick, prepping for his song. Fred Willard and Catherine O’Hara were in the hallway as well, sitting in folding chairs, and I remember doing some mime around them: you know, the hand wiping the smile up, showing “comedy,” and then the hand swiping it down to a frown, showing “tragedy.” Catherine told me she was actually nervous, and I said, “Yeah, me too!”

Now, this is the genius of Catherine and Fred: In the outline for their characters, Ron and Sheila, it said, “Ron and Sheila audition for the show by reenacting their favorite coffee commercial.” It was their idea to sing “Midnight at the Oasis” and incorporate the coffee commercial into the song. Chris’s friend David Nichtern had written the song, so getting the rights was easy. It was Lewis Arquette’s choice to wear jazz shoes with his overalls. Where and how would this man, who worked as a taxidermist, dig up jazz shoes? That was the best. Bob babysat the Arquette kids in Chicago, so they went way back. I think that the Arquettes had vaudeville genes and the Balabans ran theaters in Chicago. Bob’s character was a beekeeper, and he had researched and prepared all this stuff. I seem to recall his entering rehearsals wearing a beekeeper’s suit. It’s absurd that none of this stuff was striking us as funny while we were rehearsing it. It was more like realizing that people are really interesting and more odd than we think.

Initially, in the film, when Corky (played by Guest) didn’t get the $100,000 in funding that he needed to produce his original musical, he ended up in the ICU with a feeding drip in his arm, and we all visited him in the hospital. Catherine and I were crying, holding each other and the gifts and flowers we’d brought. Trying to get him to come around, we said, “Come back to us, Corky, please, we need you. We can’t do the show without you … come back, come back …” After this first take, Chris asked for a banana, which he put at his groin, giving Corky an erection.

In editing, I guess he felt he’d taken it too far, or the whole thing went on too long (like a minute instead of 20 seconds) and so the scene ended up on the cutting-room floor. In its place was a quick shot of Corky in the bathtub, with one of those funny ice packs on his head. This sort of understated subtlety runs throughout the movie. Not a lot of people notice this, but in my final interview scene, there’s a quick establishing shot of a handicapped parking space — with an empty wheelchair parked in it. What person would park their wheelchair in a handicapped parking spot and be able to leave it? I didn’t notice it, either, and I was there when we shot it.

The Guffman cast really felt like a family, a good comfortable family. Fred would smoke his cigar, looking out at the landscape of Lockhart, Texas, his mind reeling with funny things. I was very sad the last day of the shoot, because I’d never see Corky again. I cried in the van and Chris held my hand. I remember seeing my first gray hairs on that film.

Soon after we wrapped, I was at the Joyce Theater in Chelsea seeing a dance piece, and I saw a man who looked just like Corky: same wig, same style of dress, same mannerisms. I was so happy to see Corky that I called Chris to tell him. That was the summer I sat out on the scaffolding of my apartment as if it were a porch and talked on my cordless phone, close to my fire escape. I’d call down to passersby that I was running for mayor and then hide to watch them look around.

Best in Show is a movie everyone loves. No one’s ever said they didn’t like it, and if they did, I would run away from that person. I’m always shocked when I hear, “The person you played is my sister!” or “She’s just like my wife!” I mean, that’s nuts! The woman I played screamed at her husband at airports, was maniacally entitled and demanding, and threw fits and yelled at hotel managers and pet-store owners. I guess we all get to that point sometimes, though? I have, obviously.

Probably the best compliment I ever received was in the parking lot of a Lowe’s in upstate New York. This man had his 5-year-old son with him, and he said, pointing at me, “This is the crazy dog lady from Best in Show,” and the little kid started laughing. I mean, done. Nothing makes me happier than a 5-year-old boy laughing at a grown woman acting like a 5-year-old.

Michael Hitchcock played my husband, Hamilton, in Best in Show. I played Meg Swan. The script outline described them as a “catalogue couple” with nothing in their homes that was personal to them. They fell in love at Starbucks. They’re both lawyers and seeing a therapist because their dog, Beatrice, has had anxiety since she caught Meg and Hamilton having sex. They’re very nervous because they very much want Beatrice to win Best in Show. When it comes time to shoot, the characters fill in the blanks with the history and details. So much is cut, like a scene in which Beatrice had pooped in Ham’s slipper to punish us. In the scene, I accosted the maid when I saw this very deliberate attempt Beatrice was making to communicate to me that she was upset — jealous, in fact. I held the slipper and showed it to my maid. “What is this? Do you see this? Why did she do this? Why aren’t you answering me? Were you here when it happened? What happened — tell me! Don’t I pay you? Why aren’t you speaking? You’re fired!” It didn’t make the film, but who even dreams up a dog who takes revenge by pooping in a slipper? Chris does.

One afternoon, Hitchcock was in an animal-training class, which I skipped, because I felt that for Meg, the dog didn’t really “matter,” it was her attachment to the dog that mattered — her projections of herself onto Beatrice. After Hitchcock’s training class, we had lunch with Chris (his process is a whole other form of “laid-back”), and he said, “What if you two had braces?” Hitchcock and I were like, “Mmmhmmm, yeah, okay.” So Michael got a retainer with the braces attached, which gave him a lisp, which suited his character, and I got real braces since I didn’t want a lisp.

Our dog was originally supposed to be a pointer, which was very J.Crew, so we were ready to go shopping there. But then Chris heard that pointers were too difficult to train, so we switched to a Weimaraner, which seemed very Banana Republic to us. At that point, Banana Republic had ventured far away from their safari “chic traveler” gear of the ’80s and landed in the gray-slate-taupe period: cashmere wool capes, pointed shoes (very Weimaraner), and cashmere key-chain balls. I could put that gray cape on and slouch and feel brittle and sad that Hamilton wasn’t paying enough attention to me.

I remember having lunch with Chris one day, and he said, “That’s a nice sweater,” and I was in a bad mood and said quickly, “It’s Banana Republic,” and he said, “Okay.” I caught myself being in character. Funny stuff happens around Chris.

It’s not just that people are trying to be funny around him, to impress him; these moments just seem to happen in normal situations, like in an elevator.

He’ll watch and observe and make mmhmm sounds to the everyday people all around him, like people who have the same hair as their dogs, or a grown man with a Little Lord Fauntleroy wig as hair. I was at a place I like called Peacefood once, and there was a cauliflower special, and I asked the waitress to tell me about it, and she said, “It’s a vegetable that tastes like broccoli, but it’s white.” People are so funny when they don’t know what they’re saying.

Before we enter into a scene, the main direction from Chris is: “This isn’t too far from the truth. People are really like this.” The irony is that he inspired an ironic or postmodernist position in comedies today, but he couldn’t be further away from irony. The other irony is that for such funny movies there’s disappointment for the actors when they see the final product, since so much of everyone’s performance gets cut. There’s no clause with the Writers Guild of America for improvising being seen as writing but maybe one day there will be. As is the case on Woody Allen’s films, no one gets paid anything, so you do it for the sake of the art. Chris doesn’t do the awards circuits, so great performances worthy of them are left to legacy. I’m thinking of Catherine in For Your Consideration — she was so funny and painful, just genius. Life imitated art for her that year because, like in the film, there was talk in the biz of her receiving an Oscar nomination. He gives us our very own medals, though, made especially for the production, with the title of the movie written on a round medallion that hangs by a red, white, or blue ribbon. I have four of those medals and a few Oscars of my own. They’re the souvenir-size ones from LAX, but still, it’s something.

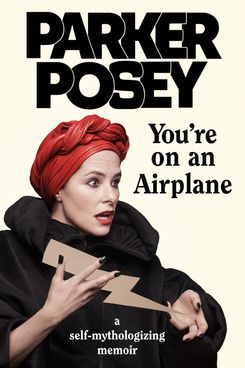

Excerpted from You’re on an Airplane, by Parker Posey, published July 24 by Blue Rider Press/Penguin Publishing Group/Penguin Random House. Copyright (c) 2018 by Parker Posey.

*This article appears in the July 23, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!