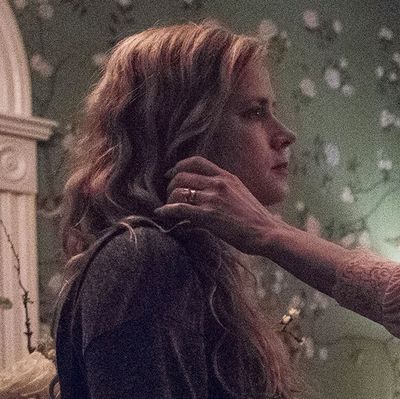

“Dead girls everywhere,” laments a character in HBO’s Sharp Objects. She’s talking about more than the preteen bodies found piling up in Wind Gap, Missouri, where hometown gal Camille Preaker (Amy Adams) has returned to write a story for her St. Louis newspaper and come to terms with her haunted past. Based on the terse and haunting debut novel by Gillian Flynn (Gone Girl), this eight-episode series is in part about the spirit-killing exploitation, manipulation, and negative messages that drive women of all ages, classes, and races to hurt themselves and other women. (Camille is a cutter whose body is inscribed with so many messages that when she goes out in public, only tiny slivers of skin are exposed.) Yet Sharp Objects embeds its cultural observations so deep in the fabric of its story that it never feels like a message-delivery device that just happens to have characters and a plot. And, much like David Fincher’s gory black-comedy movie adaptation of Gone Girl, its ultimate resolution will likely have critics arguing about whether it’s part of the problem or the solution.

Labeling Sharp Objects a small-town mystery or a crime thriller feels a bit like false advertising, even though the story is sparked by the ongoing investigation of one girl’s murder and accelerates with the discovery of a second corpse. As overseen by writer-producer Marti Noxon (Dietland), series director Jean-Marc Vallée (Big Little Lies), and Flynn (whose name is on three of the scripts), it’s a psychological exploration fused to an anthropologically detailed account of early-21st-century small-town American life. It moves at its own peculiar yet confident pace, inserting silent or nearly silent flashbacks into present-tense scenes and fragmenting montages with flash-cuts of images that confound and tantalize the viewer with the promise of revelations to come. The editing (by Vallée) is free associative yet always on point, yoking its stylistic flourishes to the psychology of Camille and a handful of other major characters, including her haughty and cold mother, Adora Crellin (Patricia Clarkson), the heir to a hog farm that employs most of the town’s citizens; Adora’s silently enabling husband, Alan (Henry Czerny); her prematurely worldly 14-year-old stepsister Amma (Eliza Scanlen), who literalizes the idea of a “fast girl” by zipping around the county on roller skates with her flirty, giggling friends; Kansas City detective Richard Willis (Chris Messina), who is building a theory about the whodunit but won’t share it with our heroine; and Wind Gap’s police chief, Vickery (Matt Craven), who blames Camille’s reporting for inflaming a citizenry already cratering from grief and fear.

It’s fitting that a series titled Sharp Objects would be propelled by its cutting. The literary adjective Proustian is overused, but the storytelling here earns it. As guided by Flynn and Noxon’s vision, it’s the culmination of a style that Vallée, a director-editor, has been developing throughout his career and that was brilliantly showcased on Big Little Lies. Drawing on classics of nonlinear, flashback-driven filmmaking, including Hiroshima Mon Amour, Picnic at Hanging Rock, and Don’t Look Now, it’s genuinely cinematic. Narrative architecture and character psychology are married in every scene and usually conveyed through music and sound cues, recurring close-ups of artfully framed objects (fans, roses, blood, a spider, a cherry impaled on a fork tine) and people (girls on skates, boys pointing guns), and the expressions on people’s faces (Adams’s in particular; she’s as good as Terence Stamp in The Limey).

Sharp Objects is also a showcase for a ridiculously overstuffed ensemble of great character actors both familiar and new. Craven, a sinewy action-film second banana back in the ’90s, is reborn here as a sandblasted icon of midwestern machismo, with the face of a gunfighter from an Old West daguerreotype. Elizabeth Perkins, an actress you’re never not thrilled to see, plays a boozy flirt who kills time in the town’s only decent bar and is annoyed that she could put her hand on Willis’s thigh for 15 minutes without his acknowledging it. (“I’m not one to talk about other people’s touchy areas,” she purrs to Camille. “Not when I’m sober, anyway.”) During the first few hours, Czerny is mainly on hand to suffer silently, but toward the end, we get a sense of just how much pain his character is stifling, and it’s heartbreaking. The standout, though, is Clarkson, the rare performer who can seem naturalistic even when giving the sort of performance that Vivien Leigh or Bette Davis could have in the glory years of black-and-white. Everything about this rich, emotionally constipated woman’s demeanor drips with misery as well as privilege, and her southern Missouri accent, which daringly verges on florid, is hilariously perfect for pronouncing the word “veranda.”

But whenever Sharp Objects seems to be on the verge of spiraling into contrived pot-boiler absurdity (which is often, particularly in its latter half ), the quicksilver filmmaking and Adams’s exact and understated lead performance pull it back. Nearly as striking as the series’ depiction of male entitlement and female self-excoriation is its portrait of a town so small that there’s nothing to do for fun except gossip and lie, skate around, drink and do drugs, have sex with anyone who’s willing, and wander into the same dark woods where a serial killer might lurk. Scored partly to a playlist of Led Zeppelin’s greatest hits — contained on an iPhone whose narrative significance is explained in a series of wrenching flashbacks — it’s a cul-de-sac travelogue that moves in increasingly desperate circles (much like the blades of the ceiling and wall fans so often pictured in evocative close-ups). Camille can’t get through a day without running into other women who remind her that she used to be the town “slut,” and girls (including her own wild-child half-sister) who have absorbed the same toxic messages reflexively spit at them by other girls, some younger than themselves. She drives and drives, then drinks vodka from an Evian bottle and drives some more, looking out the window at the present and seeing people and places that remind her of the past and failing to resist the urge to score her skin with the same words she hallucinates on the sides of boxcars: Wretched. Trash. Bitch. Every word and image cuts like a knife.

*A version of this article appears in the July 9, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!