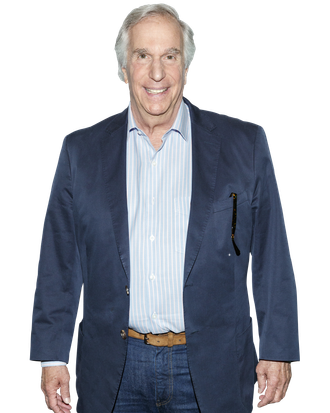

Henry Winkler knows exactly what I am going to ask before I can finish the question: “Have you thought about what you’ll say if you win the Emmy?”

“I can’t think about it,” says the actor, who was recently nominated for an Emmy for his portrayal of self-involved acting coach Gene Cousineau on HBO’s Barry. “I’m just happy.” Then he adds: “What will be will be.”

It’s understandable that Winkler doesn’t want to jinx himself. The man who gave birth to the coolest TV character of all time, Arthur “the Fonz” Fonzarelli from Happy Days, has been nominated on five previous Emmy occasions — three for his work on Happy Days, once for his narration of the documentary Who Are the Debolts and How Did They Get 19 Kids?, and again in 2000 for his guest role on The Practice — but he has never won. Some prognosticators are saying this could be his year. You won’t hear that kind of talk from Winkler, but during a recent phone interview, he was happy to discuss his Emmy memories, how his own acting instructor experiences informed his take on Gene, and how he still deals with, and overcomes, dyslexia on the job.

It is such an honor to get to talk to you. Happy Days was my first favorite TV show.

Yay! You know what? Mine, too.

What do you remember about getting your first Emmy nomination in 1976, for Happy Days?

When I was dreaming about being an actor — of course you’re sitting in your apartment in New York City. It’s Sunday night. You’re watching the Emmy Awards, or the Golden Globe Awards, or the Oscars. And you’re dreaming about being an actor. And you think, “Will I ever be called?” Of course, you’re holding a hairbrush, or a bunch of pencils held together by a rubber band, and you’re giving a speech in your mirror, when you’re not pretending you’re Paul Anka mouthing the words to “Diana.” Then all of a sudden, you’re in the mix. You’re there, and you can’t believe it.

A fraternity brother gave me a key chain that was a piece of silver with a thumb indentation, which you rub to release strain. I must still have it somewhere. But I don’t think it worked.

You wore it to the actual ceremony?

I carried it in my pocket. It was a small, like a key fob, instead of an entire chain. I really believe that I rubbed it so much and so often that I rubbed it down to the nub. I literally removed silver.

I took it once. Then I figured, You know what? This is not working. The votes are in, and this is literally changing nothing, except that I now have a Band-Aid on my thumb.

Everybody says it’s an honor to be nominated, and certainly it is …

You know what? Here’s the honest truth. It is a joke I have made before. It is an honor to be nominated. It’s an honor to be nominated in this category. And in my case, it’s true, all of these men are really terrific at what they do. They’re very smart and funny. All of that lasts all the way down the aisle. [Then] the usher shows you your seat and you pull your seat down, and just before your tush hits the actual velvet, that feeling is gone. All you want to do is win.

You were last nominated for a guest role on The Practice, but this is the first time since the ’70s that you’ve been nominated for a regular role in a TV comedy. The way that we cover the Emmys, the way that we talk about the Emmys, has changed significantly since the ’70s. Did it feel different this time?

It was different because, let’s see, I was in Iola, Wisconsin. I was at a book signing [for] my children’s book. My incredible public relations person, Sheri Goldberg, called because it was not coming on the television in Iola. Either I missed it, or I thought I timed it right for whatever time it was on the West Coast. Here I was in the middle of the country, maybe two hour’s difference, and I missed it. But it was on when she called me, so we were listening over the phone. I was reporting to my wife sitting next to me in this bed and breakfast. They all of a sudden didn’t read off my category, supporting actor in a comedy. Then, [Sheri] said, “Okay, don’t worry. I’m going to go to my computer.” Then we walked over to her computer, I on the phone, she on her feet, and she looked up the entire list. She read off all the nominees, and the very last one, she said, “And there you are.” And I said, “And there I am.” And we danced in the living room of this B&B in this small town in Wisconsin.

That’s nice.

It was so nice. It was so exciting. Because you don’t know. People say, “Oh, sure, that’s a great character. Gene is wonderful.” But you don’t know. And there it was. My name was actually there, and I have to say, it was a really wonderful feeling. And then, that feeling fades away into, “Oh my gosh, are they going to vote [for me]?” And then you eventually move to, “You know what, you have to give this up to the universe.” Because you could worry about this from now until next Tisha B’Av. And you have no control. I’m just thrilled. I’m thrilled that I get to be part of this show, this ensemble.

The kids in my class, they call themselves the Cousineau babies. And each one of them is a home-run hitter. Kirby [Howell-Baptiste] is in Killing Eve. Alejandro [Furth] was in The Menendez Brothers. Darrell [Britt-Gibson] was in Three Billboards. Sarah Goldberg is one of the finds of the century, who plays Sally. She’s just an amazement every time. My assistant in the class, D’Arcy Carden, is Janet on The Good Place. So she’s great in two places. I’m telling you, it’s just a wonderfulness. And then there’s Rightor [Doyle], who played Nick — he has written and directed a piece that he took to Cannes. These are my wonderful acting partners.

Did you base any part of Gene on acting teachers that you’ve had?

I taught four classes in my life. They were a master class at Northwestern, and three classes at Emerson when I was making Here Comes the Boom in Boston. I realized that first of all, it is thrilling. Because the entire exercise is to see if you can have a student taste something that he or she did not think of when they were preparing the song, the monologue, the scene. To see it happen is exhilarating. Then I had 14 teachers in my life, at Emerson College and at Yale. Then I based it on people that I heard about. There was a teacher who foisted his art on the kids in his class, who are struggling to earn money to pay rent, food, and for acting class. And you’ve got to buy this guy’s art.

Oh, God.

That’s crazy.

With both Sally and Barry, Gene says awful, cut-to-the-bone criticisms, but he’s doing it to get them to use emotions in their performances. Is that solely the motivation, or is there something else going on there?

I have had teachers who were brutal. If you look up brutal in a dictionary, you will see their names. And I think that it’s under the guise of wanting to change the actor’s habit — wanting to break bad habits and replace them with brand-new ones you can use for the rest of your career. Now, let me just say, as a person who went to a lot of drama school, some of that is true. I have used almost every inch of what I have learned along the way. Even in slow-motion work, which I used in the [Happy Days] episode with Mork from Ork, with Robin Williams, when he froze me, and then moved me in slow motion.

I remember that.

I did that at Yale in class. But on the other hand, sometimes it’s so mean that I’m not sure habits are involved. I’m not so sure. When I was a freshman at Yale, one teacher brought me up after class, and said, “You’re trying to undermine my class.” And I thought to myself, “Oh my God, I’m going to be kicked out of school on the first week.” Not only do I not have a sense of self, I don’t even know what she’s talking about. I don’t even know how to undermine anything.

What made her think that’s what you were doing?

I don’t know, maybe because I was a smart aleck. Maybe because I couldn’t control a joke. If I saw something funny, it came flying out of my mouth. But let me tell you that at that moment in time, I was like the bowl of Jello before it solidifies when you put it in the refrigerator. I had no idea what the hell that woman meant. That’s not even hyperbole.

In your children’s books, and just generally, you’ve been very open about dealing with dyslexia. How does that still affect you? Did it affect your work on Barry in any way?

It has affected my work since day one. When I audition, I read very poorly. To this day. So I read slowly, and I memorize as quickly as I can. And then the rest, if I don’t know it, I make it up. I have done that my whole life. My son, Max, our youngest son, directed me in the audition [for Barry]. He looked at the script. We went over it, and he went, “Dad, respect the writer.” I said, “Max, I’m doing the best I can.”

That’s got to terrify you when somebody says that. You don’t want to make a mistake, but like you said, you’re doing the best you can.

Yeah, well, he was relentless. I went in, and apparently I got the part.

In terms of doing the work itself, were there opportunities for you to improvise?

There were, and there are. If Bill [Hader] didn’t say to me one time, he must have said it 6,000 times, in the most patient way you’ve ever seen: “Could you please just read it once the way it’s written, so I can hear it?” I’m trying. I am, I swear to you. Sometimes the improv would be in, and sometimes they would gently say, “Could we just do it again?” And there was no drama on the set, except for the drama written into the script. I always say that Bill, when he is producing, writing, directing, and starring at the same time, he moves — in drama school, we had two teachers come in who were tai chi masters to teach us tai chi, which would center us, which would then help us with a calmness onstage — and I often say that Bill moves without moving air. It all seems effortless. Now, I don’t know what happens when he goes home. But I’m not joking. You can come to the set and witness what I’m witnessing. It’s there on display. It’s really quite something.

And [series co-creator] Alec [Berg], the same thing. Calm. I like to say that Alec is so Norwegian, he’s so close to the vest, his vest is painted on. And then he whispered to me once, he said, “Actually, I’m Swedish.” I said, “But could I keep saying Norwegian? I think it’s funnier.” He said, “Yes, you can.” Oh my God, we’re starting again on the 18th of September. And talking to you now, I swear I can’t wait.

Have you seen the scripts yet?

We did. We saw two scripts in, I want to say, May or April. And now we’re going to read them in two weeks. Bill, Alec, and [writer] Liz Sarnoff are all nominated for Emmys. Holy cow.

I’m curious: If Henry Winkler, not Gene, could give acting advice to Barry, what would you tell him?

You mean sincerely?

Yeah.

There’s got to be a way to clear your mind. There’s got to be a way where you listen to only what is being said on that stage, in that acting space. In that, you’ve got to clear your mind. If you clear your mind, you can fill it with your character. If it is cluttered, if it is anxious, if you’re thinking about your date, about your dinner, about filling your refrigerator, there’s no room. There’s no room for the character you’re trying to build. Does that make sense?

It does make sense. It seems like Gene doesn’t necessarily pick up on the clutter that is in Barry’s brain.

Nor in his own brain. He is so fatootsed. He is so … Gene is just crazy.

You also have the benefit of knowing some information about Barry that Gene doesn’t.

Yeah, right. And that’s a lot of clutter. A lot of dead bodies roaming around that brain.

I was reading an interview that you recently did with the New York Times …

About the pizza?

About the pizza, yes.

Can I just tell you something?

Yes.

I have done this a long time. I have been interviewed since 1974. That I got to go [to Lucali], to that place, and literally make the pizza from scratch? And then I walked with him, Mark [Iacono], the owner, through the neighborhood? It was like The Godfather, I’m telling you. We walked into the sausage place: Get over here, I wanna take a picture with youse. I mean, I have never been that safe in my life. In the bakery. And just walking through the neighborhood with him, every human being: “Hey Mark, how you doin’? Mark, good morning. What’s goin’ on? How’s your car?” Oh my lord, it was like I was walking with Brad Pitt. And then I got to make this pizza. I loved it, I really did. But anyway, I digress.

I would think that you have similar experiences yourself, just walking around.

I do, but not like when you’re with Mark.

You said something in that interview: “It took me this long to be close to the actor I knew I wanted to be.”

Yeah, that’s true.

Tell me more about that.

When I was 27, I got the Fonz. Because I changed my voice, and I changed the tilt of my body, that actually was a key that unlocked my imagination. What we talked about before, about removing the clutter from your mind? Changing my voice was like pulling the plug on the drain, honest to God. I could do anything with my new voice and my new swagger. It was, I don’t know what, but anyway I thank God, let me just tell you that. It was fun, and I loved those people. It was just an amazing ten years.

I knew then who I wanted to be as an actor, but when I didn’t have that key to unlock my mind, I’d like to have some of those performances back. The One and Only. Heroes. I wish I could redo them. I just couldn’t get a handle on what I knew I needed to do, and what I was able to do. So now that’s 27. All the way, here I am, 72. I could not have played Cousineau back then, going back down all those years. It had to be now.

Do you think you’re better at removing the clutter than you used to be?

There’s still clutter. I still have a ways to go, but just between you and me, I am light years from where I started. And I am giddy. It makes me happy.

Well, I am rooting for you to win an Emmy.

Thank you. What a nice thing, Jen, thank you.

Who could not be rooting for you?

You never know. We’re going to find out.

This interview has been edited and condensed.