Every great hip-hop saga is, at its core, a story about friendship. Before “Push It,” “Whatta Man,” and “Shoop,” Salt-N-Pepa was just Cheryl and Sandra, community college classmates and co-workers. OutKast’s vibrant music and motion picture career grew out of the bond between high school besties André Benjamin and Antwan Patton. The West Coast mainstream hip-hop boom of this decade is attributable in part to the connection between three Los Angeles friends. In 2009, rapper YG was a gang-affiliated Compton youth whose aspirations of rap fame were nearly derailed by time in jail for burglary. Mustard, YG’s DJ, taught himself how to make beats to advance the rapper’s mixtape career with help from Ty Dolla $ign, the son of a funk musician, and a formidable singer, songwriter, and producer in his own right. YG and Ty scored a minor hit in 2010 with “Toot It and Boot It,” and Mustard’s production on YG’s 2011 mixtape Just Re’d Up brought him to the attention of savvy street-rap fans. Later that same year, Mustard’s mid-decade rap chart regency began with the Tyga smash “Rack City” and stretched out across hits on Ty’s 2013 mixtape Beach House 2 (see: “Paranoid”), YG’s 2014 debut studio album My Krazy Life (see: “Left Right” and “My Nigga”), and albums by Rihanna, Jeremih, and Big Sean.

Relations between the three friends hit a snag in 2015, when a dispute between Mustard and YG over fees and royalties spilled out into threats on social media. The once-inseparable rapper-producer team parted ways, and YG’s sophomore studio album, Still Brazy, released in 2016 without any Mustard input. Brazy was a critical and cultural success thanks to paranoid autobiographical cuts like “Who Shot Me?” and the protest rap “FDT (Fuck Donald Trump),” but it didn’t match the commercial impact of the first album. The pair have patched things up since then, and this summer’s Stay Dangerous documents the renewal of the partnership. The new music leans heavier on the rowdy party raps of YG’s mixtape era than the intricate storytelling of Krazy and Brazy, in large part because recording it was a blast. It’s bratty and funny on the Right Said Fred interpolation “Too Cocky,” but deadly serious on deep cuts like “666” and “Bomptown’s Finest.” The latest single, “Big Bank,” is creeping up the Billboard Hot 100. (Mustard’s also riding high on that chart as the producer of Ella Mai’s ubiquitous summer smash “Boo’d Up,” and Ty Dolla $ign is the only person in the hip-hop business with the juice to appear on Drake, Kanye, Jay-Z, and Beyoncé albums in the same summer.)

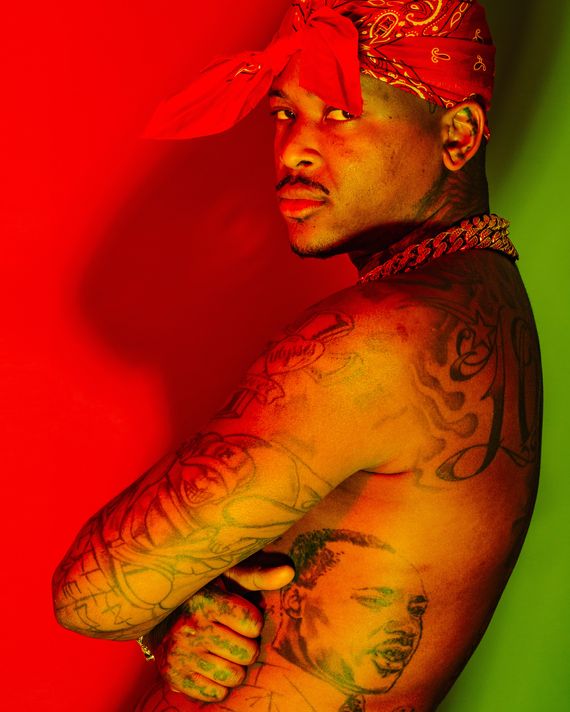

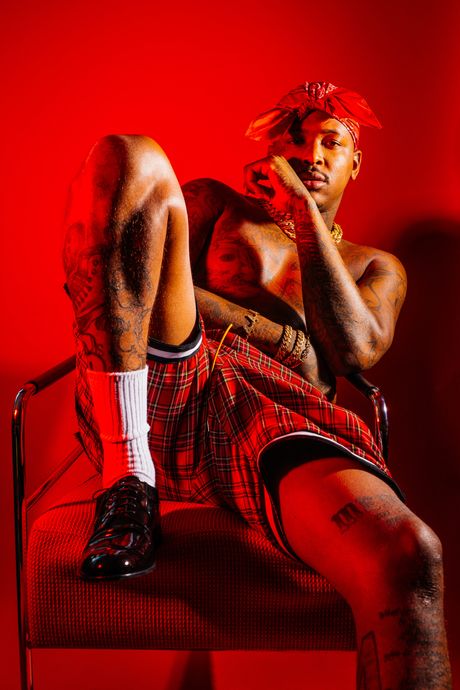

YG visited the Vulture office this week to chat about friendship, fatherhood, mentorship, mental health, and Stay Dangerous as another step in his decade-long journey with Mustard and Dolla $ign. He also spilled some early details about the future of 4Hunnid, his label and clothing line. His ensemble — a black hoodie, red plaid shorts, shiny black loafers with high white socks, and his trademark thin black sunglasses — was expectedly tremendous. The clothes, like the man wearing them, are an undeniable mix of street-savvy and lighthearted.

I was hoping you would come through in the sunglasses. I was wondering where you got those.

They’re called Roberi & Fraud or something. It’s, like, an overseas brand.

So, our fashion section, The Cut, recently called you a “style icon.” I respect you bringing that flashy Cali street flair with the 4Hunnid line.

Oh, for real?

Yeah. Artist merch usually comes in two tiers: There’s the $30, $40 stuff printed on regular cotton, and then there’s the Beyoncé, Kanye stuff that’s higher end. It seems like you’re trying to get into the middle of that and have something that’s a little upscale, but still affordable. I was wondering if you were consciously doing that.

Yeah, we’re for sure consciously doing that. But we got different tiers of the 4Hunnid brand. We got the lower: the regular printables, the T-shirts, and the hoodies. Then we got our cut-and-sew line. Then we’re gonna be doing special capsules with different retailers like Barney’s. We’re gonna have a Barney’s collection. Different collections for higher-end retailers. And that shit gon’ be expensive. But our mid-price products … probably anywhere from $40 to $150, $200. That’s the shit we sell online. And then the higher end shit gonna be Barney’s and all that other stuff.

A lot of streetwear is kind of thirsty to have a connection with the streets, but when you look at who’s making the stuff, it’s not so many people coming from the streets.

Yeah.

And you’re trying to bring a change to that industry?

That was definitely a part of the conversation when I was talking to the homie about relaunching this 4Hunnid shit. One of the things I’m trying with the brand is representing the streets. And we got real street motherfuckers behind it. And it’s paying real homage to the streets. Cause a lot of these brands, they steal from the culture, steal from the people. They don’t really pay homage and give back. They don’t do nothing like … I’m using models from the streets. The homegirls from my hood. I’m using the homies from the hood. For certain shit, I’m making sure they’re a part of the whole situation. I’m using real models too, also. But I’m blending it in for sure.

In “Su Whoop,” you spoke out against fake Bloods. Do you feel like people are getting too cozy with gang culture, who have no connection to it?

I mean … Yeah. Probably due to the internet. But it’s a good thing for motherfuckers that’s really from the gang culture, cause you can benefit off of it. [Laughs.]

On the cover of the new album, you’re in a leather vest, and it looks, to me, like 2Pac from All Eyez On Me. It seems like you’re moving towards that stylish gangster vibe that he had in the mid-’90s.

2Pac was probably the flyest nigga on the West Coast back in the day, for sure. He was playing with the fashion shit. I feel like my swag, how I dress, is different from how he was dressing, but you can compare us as far as being from the West Coast on some fashion street niggas. I guess you could say I’m picking up where he left it off.

So, you have the clothing line, you have a label, you made a short film … is stepping up your business game about making sure you’re set for a future outside of rap?

Hell yeah. It’s mandatory.

I want to ask about titles. I feel like you have the best series of album titles right now. You had My Krazy Life, which was you introducing yourself to people who didn’t really follow the mixtapes. You had Still Brazy, where you’re maintaining. So I was wondering what the thought behind Stay Dangerous was.

Stay Dangerous, man. The concept behind that is staying on your shit. Staying ready. Staying on the edge. Staying ten steps ahead of the next motherfucker. Not just your enemies, but everybody. Being proactive, not reactive. Knowledge is dangerous, you know what I’m talking about? So yeah, when I say “stay dangerous,” I mean all that. It ain’t really like, as far as the album concept … The last two albums I did, it was like, deep storylines … I don’t really got no deep-ass storylines and shit. Like, this song connecting with this song ah ah ahhh. It flow right. I put it together right, but it ain’t no deep-ass storyline.

The new one reminds me of your mixtape stuff, like 4 Hunnid Degreez and Just Re’d Up. Were you trying to get back to that style?

Yeah, because me and Mustard, we went so long without working with each other and feeding the people what they wanted from us. My main focus was doing that. It was like, fuck, I ain’t about to spend all this time trying to do some deep-ass shit. We ‘bout to come turn up. And we ‘bout to make some real music though. We ‘bout to make some hits. I’m gonna put this shit together to where it feel like it’s a real album. So getting back to the basics was definitely a priority.

You’ve worked with Ty Dolla $ign for about ten years. It’s ten years since “Toot It and Boot It,” right? Now, the two of you get to work on tracks with Nicki, and Drake, and Kanye, and Beyoncé. Talk to me about that growth.

Ty always was the most talented of the group on some musician shit, on some musical shit. He was always big bro. He was teaching us shit. He was helping Mustard when Mustard started making beats, cause Mustard wasn’t making beats at first. He was my DJ. He was just DJing. He started making beats. Ty used to give him advice, sounds, and all type of shit. It feel good to see the homies that you came up with before the fame and the money. Niggas was broke. Niggas was sleeping at each other house, all type of regular shit. So it’s a blessing for sure. That shit rare, you feel me? You don’t get a group of motherfuckers that came up with each other before the success that’s not in a group. We ain’t no group. We homies, though. We was all from the same clique. And we all got our own shit going on. That shit crazy.

Most musical partnerships don’t last ten years. How do you keep the energy going?

Niggas just be having real conversations with each other. When me and Mustard was going through what we was going through, me and Ty would talk about it. And Ty would be like, bro, fuck that, we gotta fix it … and I was like, nah, fuck that … But at the end of the day, if niggas see some shit going on that ain’t solid, motherfuckers gonna holla about it.

Try and be intermediaries for each other?

Yeah. Motherfuckers gonna holla about it. At the end of the day, niggas realize, bro, we can all do what we do on our own and be straight in life. But if we do this shit together, it’s gonna be crazy. And we supposed to do it together. Ain’t no reason why we shouldn’t. We came in this shit together. Niggas ain’t trying to be like people that came in the game with homies, then niggas got successful, and then at the end of the day, when you look back and you’re older, y’all not even cool no more. That shit wack.

The connection is more important than the fame.

Hell yeah. That’s why, with me and Mustard … it took us so long with the music because we were separated from each other for so long. And a part of the reason of how the sound got created was because we was on some homie shit, hanging with each other every day. So this nigga knew what type of shit … he knew all my little shit. I knew the homie. I knew how to get out what I need to get out from him. He know how to get out what he need to get out from me. Because we spent that much time with each other. So we had to spend that type of time again, on some regular shit. Just in the studio, talking, just being regular. Me and bro, we like neighbors. We live in the same gated community and shit. Our kids be hanging with each other every day.

You had to get back on a friendship level before you could get back into the studio?

We had to. It’s like, niggas is homies first. So it’s like, if you create some artistic, artsy shit, whatever the fuck with your friends, and y’all fall out, and y’all ain’t even friends anymore, you gotta get back to being friends before y’all get back doing art shit. Cause if y’all ain’t friends, the art shit ain’t gonna come out how it was coming out when y’all was making shit when y’all was friends. We was making music the whole time, but I already knew, I told bro, it’s gonna be a process, we been working with each other for whoopty whoop however long. Let’s just work. It’s gonna come and come. And that’s what happened.

When you record together, is he making beats while you’re there, or is it just like, “Come over, I got something?” How does that work?

Like, “Big Bank” … Shit, all that shit on the album was made from scratch. “Big Bank,” “Power,” “Too Brazy,” “Too Cocky.” Them four was made from scratch. And then “Slay,” he had already played me “Slay” with Quavo on it. He gave me that. What others … “Bomptown Finest” was … I did that whole song to a whole ‘nother beat when me and Mustard wasn’t cool, back in 2015. And then we got back cool, I played it for him, and he’s like, “Let me redo this beat.” So he redid the beat and played it for me, right before my album was damn near done, and I added the third verse to it. So that song was done different. The “Power” shit … I think I said that was done from scratch.

Talk to me about “666.” That’s a Mike Will beat?

Yeah.

How did it come together? That’s one of my favorite songs on that album.

I was in the studio in Atlanta, October, November trying to figure out the album. That’s when I came up with the Stay Dangerous title concept. Mike Will was in the studio with me every day. He was pulling up, he was having producers pull up. He had this one young white boy pull up named Ziti. One of his new producers. He like a little Murda Beatz–looking motherfucker. He young, though. He like a little kid. He pulled up, and I’m like, “Bro, I need some shit. I need some hard shit.” He’s like, “I got you.” I’m like, “You sure?” He started pressing play … Shit crazy. I’m like … “This little nigga got it.” I did another joint on his shit. I did a couple of joints … We got some shit. Got some shit in the cut.

As a West Coast artist, are you conscious of how well your music plays outside of Cali?

Yeah, for sure.

Are you worried about getting boxed in by being too specific and too consistent with the sound?

Nah, hell nah. Cause with that, what you do … you continue to build your brand, build your celebrity. And with that, you take your sound, and you make it universal. It makes you universal. You just need some great records. And all that shit just gonna be nothing.

Does working with guys like Rocky, and 2 Chainz, and Big Sean from outside regions help expand that appeal a little bit?

Yeah, for sure. Expands the sound, the appeal, and everything.

In “Deeper Than Rap” you talk about being a father, and feeling like you work too much to be around as much as you want to. And I feel like a lot of rappers have kids, but we don’t hear that honesty. Is it tough balancing your time? How does that work?

I dedicated my life to this music shit back even before my daughter came into play. It’s really for the best for all my people. So when I’m gone, it be like, shit, I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing, because if I wasn’t doing this, I’d be at the house trying to figure out what the fuck to do so my people be straight. So it’s like, I be having that thought, but then I be having that in my head too. Like, I’m doing the right shit, but I’m gone, though … I’m around her, but I be gone a lot. But she lives with me. So I make sure I go the extra mile. I do the extra shit, a lot of times, just to make sure my daughter … she knows who daddy is, she knows what’s up.

Is it stressful feeling like you have to carry a lot of people? Like, if you don’t work, then a lot of people aren’t eating?

Yeah, bro, that shit crazy. This shit cray-cray-cray-cray-cray-cray.

You write a lot of songs about pain and struggling, and I think it’s important to hear that in the community, especially in hip-hop because there’s a lot of artists going through it. Talk to me about the process of getting knowledgeable about mental health.

I just found out what mental health was because [film producer and inmates’ rights advocate] Scott Budnick and his team put me onto this shit. They were trying to have me talk to some kids about mental health and I was like “I don’t know what mental health is. You gotta tell me.” So, they start breaking it down and I’m like … I’m a victim of this shit. You know what I’m saying? When they told me what mental health consists of, that’s when I felt like I was a victim, and I put it in a song.

A lot of the time we feel like if it’s not for an infection or a broken bone or surgery, we don’t need to see a doctor.

Yessir.

So, what’s the game, going forward? Is Just Re’d Up 3 still “coming soon”?

I don’t know, dude.

You got joints, though, you said.

A lot of these records came from the Just Re’d Up concept, but that concept … it just don’t … That title don’t hold no substance to me with what I got going on now. Just Re’d Up … that’s cool. You feel me? That shit creative. This whole shit we got going on now is taking what we started and adding real shit to it. That’s why I switched it up from Just Re’d Up. I went through like four different albums, bro. I had four different albums all filled with different music.

With different tracks?

Different tracks.

What are you doing with that stuff?

We’re figuring it out right now. But you know every rapper got that shit going on.

I talked to Jeezy around Trap or Die 3, and he said that you have a very specific idea of what you want to do with your music, and sometimes he’ll suggest stuff to you, but at the end of the day, it’s your decision. A lot of artists on labels don’t have freedom to make those decisions for themselves. So, CTE is a good situation? How’s working with them? Jeezy, that’s big bro. I wasn’t about to just meet somebody and let them come in and try to run my life and shit like that, tell me do some shit, and I do it. I met Jeezy, and we was just vibing. Over a period of time, he became a like big bro. Over time, the shit he was telling me, I saw the shit play out in real life. I was like yeah, the nigga telling me some real shit, some right shit. Jeezy is the nigga I’ll go to and press play and ask that nigga everything about the record. “What you think about this? What you think about this?” Yeah, so working with bro is solid. He’s for sure one of my mentors and all that.

And so you’re trying to do that with 4Hunnid [Records], mentoring other artists and growing them?

Yeah, yeah, for sure. It’s mandatory.

Who are you looking at as far as signing? Are you thinking of picking anybody up?

No, we just started right now. We got enough artists right now. We focused on building our artists and things and making shit pop off. We got Kamaiyah. Me and Mustard are 50/50 with RJ. 4Hunnid Summers. Rich, Slim 400, Sad Boy [Loko]. Those are our artists right now. They the main focus. I probably won’t sign no other artist no time soon. My next artist is probably going to — nevermind, I ain’t gon’ tell you.

I tried!