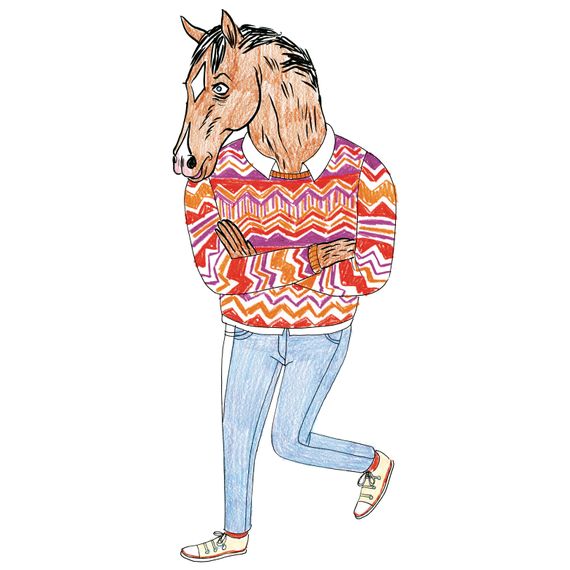

The email from Raphael Bob-Waksberg to Lisa Hanawalt on March 22, 2010, was to the point: “Hey, do you have a picture of one of your horse guys, by himself? I came up with this idea for a show I’d like to pitch. Tell me what you think: BoJack the Depressed Talking Horse.”

Lisa Hanawalt: I was like, “That sounds too depressing. Can you make something more fun and whimsical?” And he’s like, “What about The Spruce Moose and the Juice Caboose?” And I said, “Oh great, they can have cocktail waitresses called the Spicy Mice.” I think we should still make that show. For kids.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: I had gone back up to Palo Alto to teach another high-school playwriting workshop in the fall of 2010, and when I got back down, [the Tornante Company producer Steven A. Cohen] was very eager to meet me. Apparently while he was waiting for me to be available again in L.A., he kept asking my manager, Joel Zadak, to send him more stuff, so Joel eventually sent him everything he had: a couple TV pilots, a short story, a spec feature script — all the stuff I did with Olde English. He might have even sent him a link to my blog. The first meeting was a “getting to know you” meeting.

Noel Bright [executive producer]: I was on a phone call, and so Raphael came in and started talking to Steve first. Steve’s office is next to mine, and if a meeting was worthwhile or there was something urgent but he couldn’t disrupt that meeting, he’d pound loudly on the wall. It’s like our own fire drill: Wall-pound means, “Get in here.” So I got off my call and played it like I just casually walked in. Steve said, “This is Raphael.” That meant that I should sit and talk, and clearly this was a meeting that was going to go well.

Steven A. Cohen [executive producer]: Why was it “bang-worthy”? A term I already regret! [Laughs.] I don’t know if it was specifically BoJack related, but it was probably Raphael related. It’s so fun when you read stuff by people and every page you’re thinking, “This is fantastic,” and then you spend five minutes with them and you’re like, “This is really interesting.” Every day in this town you’re trying to meet someone who has something new to say or a new way of saying it, and you can feel it right away when they do. It’s exciting.

Noel Bright: There are very few creators that are able to channel what’s going on in their brain into an exciting and intelligent and cohesive story at any step of the way, and Raphael’s just a master at doing that. He’s well-spoken and he likes to pry at certain things in an interesting way.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: After that general first meeting, my manager called and said, “They really liked you. They want to meet you again because they have something they want to throw at you.” So I went back and they pitched me this property they had for me to develop, and I was like, “I don’t know, I’ll think about it.” And then my manager called and I was like, “I don’t know. I don’t think it’s for me.” And he was like, “All right, well, Steve called again, and he wants to see what you have. And I was like, “Awww, now I got to come up with my own ideas? I should have just said yes to their thing!” [Laughs.] When you live in this town you do a lot of meetings, and most of them don’t turn into anything. And sometimes you really have to do a lot of prep work.

So then I came up with five ideas — all different animated projects — one of which was BoJack. I go in again and pitch them out, and Steve asks which one of these is most interesting to me. I said, “I think the horse one is the one I really like.” Then he asks if there is anything written up, like a treatment they can look at and show around, and so I was like, “OK … I’ll get that to you.” And I was thinking, “Now I gotta do more work!” [Laughs.] And then I just forgot about it.

A month later, Steve found me on Facebook and was like, “Hey! How’s BoJack coming?” [Laughs.] And I was like, “Almost done!” And then I was like, “I gotta do it! I gotta do it!” So I wrote this thing and sent it to them. Originally there was an agent character, who was a man, and an ex-girlfriend character. In the process of preparing for the formal pitch, I combined them and made the ex-girlfriend the agent. I think some of the characters had different names and other things like that. Diane was a network executive who was going to help BoJack with his comeback before she became the ghostwriter of his book. But that was really early. That’s even before we pitched it to Tornante. I kind of settled all that down.

Then we met with Michael Eisner, and I was like, “Okay, this is for real now.” [Laughs.]

Michael Eisner [owner, the Tornante Company]: Told that there was a meeting in Steven Cohen’s office with a well-respected young writer, I happened to be in the hall as the meeting ended. In a one-minute hallway conversation, I was told three ideas. One of which being: “This one is about an animated show about a living ‘person’ who has a body of a man and a head of a horse.” Thinking that sounded interesting, original, and theatrical in this century — yet harking back to my youth of Mister Ed, the talking horse from the early ‘60s — I simply said, “Yes, let’s do that one.”

Noel Bright: Meetings don’t get to that level [with Michael Eisner] until we want to get a yes. That was the meeting to say, “This is a project we want to do. We want to go write a script and, ideally, go make a presentation — make a pilot or some test footage on our own and go sell it to a network or distributor. We believe in the idea, we think it’s great, and you should hear it — and you should hear it directly from Raphael.” The only times those meetings happen are when we’re prepared to fight for it.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: The question was: “Could it be sports? Instead of a former sitcom actor, could he be a former racehorse? And what would that look like?” I had some pitches for that, and how the story would change, but I said, “I really like the show-business angle and here’s why …”

Steven A. Cohen: I think one of the great things about Michael is that he’ll come in and try to push something to a certain place — or maybe try just to push Raphael for the first time, to see how much he really believes in this idea. I think he was impressed by Raphael’s conviction, and he was won over.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: Less on the idea and more on the, “Oh, this is a thoughtful guy who knows what he’s doing. He can make smart choices; he can do the show right.” Which is good, because now that we’re here, if it was the sports version, I don’t know how we’d do it! [Laughs.] I don’t know anything about sports or racing!

Mike Hollingsworth [supervising director]: If you’re a former actor, you can still act. But if you’re a former athlete … it’s like, “Okay, I’m going back into the NFL at age 60.”

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: The whole tagline for Secretariat — “He’s tired of running in circles” — came out of that meeting with Michael about BoJack, where we talked about how BoJack is tired of running in circles and he wants to do something else. So it was helpful! [Laughs.]

The green light from Michael Eisner to proceed was secured. Meanwhile, back in New York …

Lisa Hanawalt: I hadn’t heard from Raphael in six months, since the initial BoJack email, and then he emailed me again and was like, “I just showed your drawings to Michael Eisner!” I was like, “Michael Eisner, former head of Disney?! What?!” Then Steve and Noel brought me in for a meeting in the summer of 2011 to propose working on designs for the presentation. I was still living in NYC, and I was visiting L.A. But I wasn’t sure how much work it would be, and I was kind of commitment-phobic, so I said no.

Noel Bright: Lisa gave us kind of the opposite reaction that you could want: “So we have this show, and we’d love for you to be a part of it!” And Lisa’s like, “I’m not sure … I’m kind of busy.” [Laughs.]

Lisa Hanawalt: When I first said no, Steve emailed in response, “Best of luck.” And I was like, “Oooooohhhhhh.” [Laughs.]

Steven A. Cohen: Is it possible that I just meant, “Best of luck”?

Lisa Hanawalt: I have no idea, but to me it was like, “Oh, this is a Hollywood fuck you.”

Noel Bright: This is why I never email people.

Lisa Hanawalt: It had a period instead of an exclamation point.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: I think an exclamation point is insincere: “Best of luuUUCKk!”

Lisa Hanawalt: It could have meant anything.

Mike Hollingsworth: The worst would have been a question mark: “Best of luck?”

Lisa Hanawalt: Part of it was that I’d just finished illustrating a children’s book and it was kind of a bad experience. It took six months of work and felt endless, and I didn’t want to commit to another big project. I made the mistake of not jumping aboard a good thing.

Noel Bright: But that wasn’t actually a mistake because if you weren’t ready at the time, you wouldn’t have been happy to do it. When you eventually agreed, you were ready.

Lisa Hanawalt: I got lucky that you guys came back six months later. ’Cause you could have gone with someone else.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: [Laughs.] We did …

Lisa: Nobody could get the horse right. Is that what it was?

Noel: We couldn’t get the tone right.

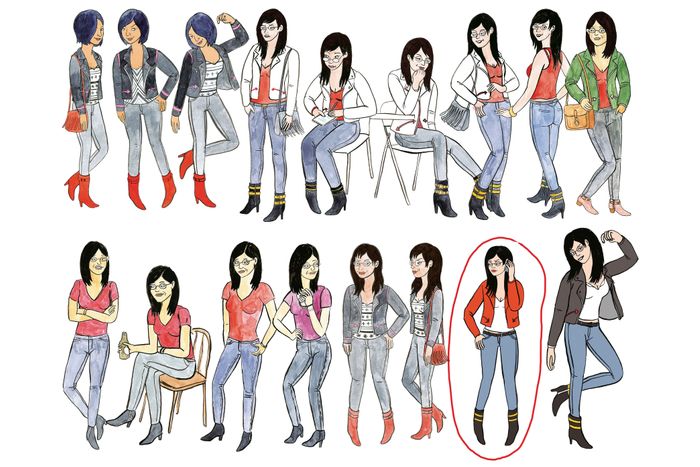

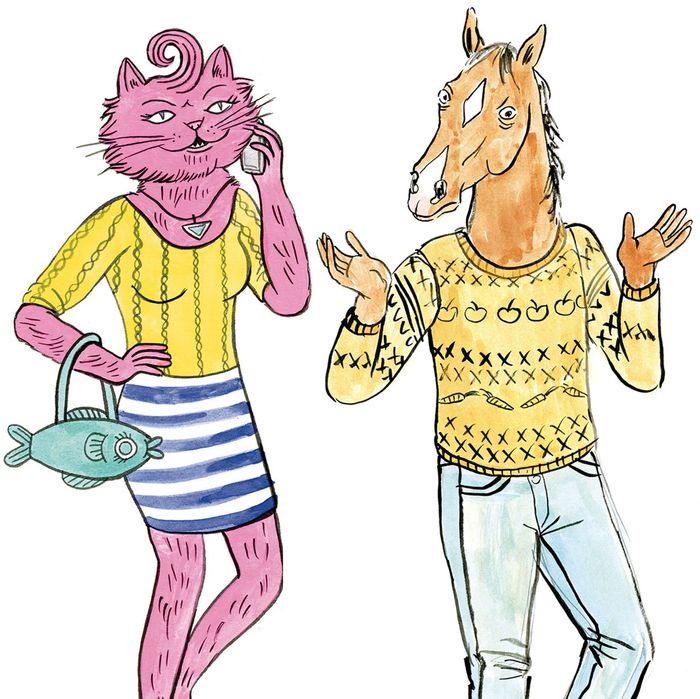

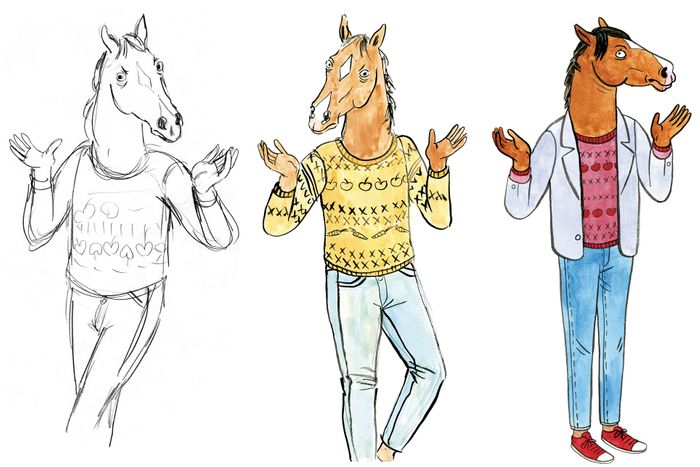

In fact, development had proceeded after Lisa’s initial rebuffing of the proposal, with several seasoned Hollywood animation pros taking a whack at formalizing the character designs for the main cast of BoJack. The qualities that made Lisa’s work unique, especially in animation, were still part of the original horse-man drawing that was seared into everyone’s imagination from the early emails and proposals. Nothing else seemed to be doing the job as well as Lisa’s indie comics line-work and curious characters, which could only hail from a Lisa Hanawalt universe.

All along, Raphael had been working on writing — glad to be working, but mentally preparing for, and expecting, the worst.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: I’m thinking, “At least I’m getting paid for these scripts, but this is going nowhere. No one’s going to buy this. No one wants this.”

Lisa Hanawalt: I feel that way about everything before it becomes a thing.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: It felt like, “Okay, this is my career now, writing stuff that never gets made, wasting my time in development for the rest of my life.”

Lisa Hanawalt: So when Noel and Steve called me six months after I said no and were like, “So … sorry to bother you, but could we ask again?” I had just joined a shared studio space in Greenpoint and was doing illustration work for the New York Times, and I was bored, and so I said yes.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: Part of your hesitation was that you were really nervous about what the job would be like and what the time commitment was, and no one could give you a solid answer. The thing we said at the time was, “Let’s just work on this presentation together, and if there’s a show, we’ll figure out what your commitment is.” We even said that if you want to walk away after the presentation, you can do that.

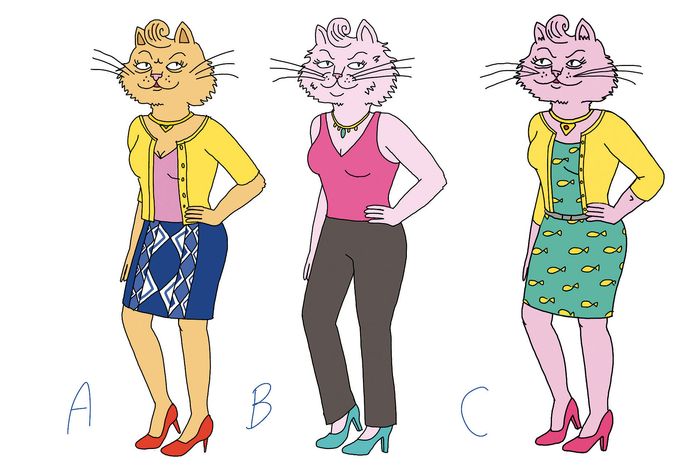

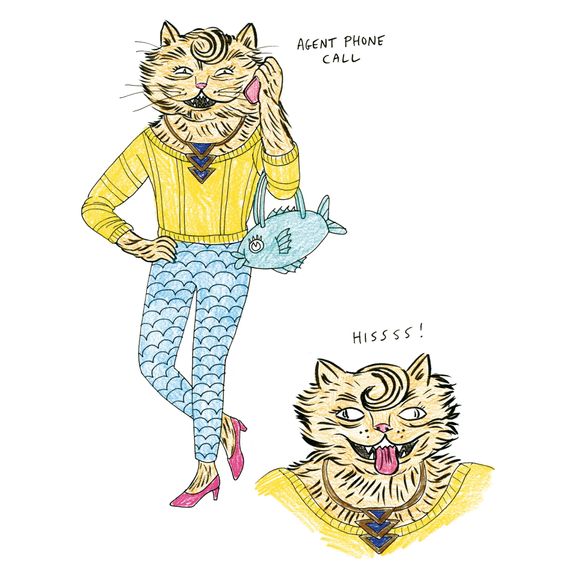

Lisa Hanawalt: And then my agent outlined super-specific things, like, “There will only be two revisions per character” — which later we threw out, of course. I did, like, ten revisions on Todd; it didn’t matter … A lot of things were set up to protect me in case I hated it.

Noel Bright: I remember those conversations with your agent: “She will do one set of revisions.” “Well, what if we want to change the color of the nose — is that a revision?” We wanted to make you feel comfortable.

Lisa Hanawalt: I’d never done anything like this, so I was just worried about being exploited.

Noel Bright: Our goal was to make a presentation. If you make it and cast it and show it, that gives you your best chance. The script process, once we hired Raphael to write the script (and he was “wasting his time” getting paid for it [laughs]), was also the beginning of knowing how it would be to work with him. We’re an independent studio, so it was immediately a very collaborative process and we wanted the presentation to be in his voice and not fuck it up.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: I had to write an outline for Tornante, and I literally did not know what an outline for an episode of television looked like. So I handed them, like, this two-page document. Now, a typical outline is ten to fifteen pages. And they looked at it and they were like, “Uh … okay. Um … [laughs]. Yeah, I don’t know … This doesn’t really look like an outline that we’re familiar with.” But I had no experience [laughs]. It was like an outline for an outline. But what’s even funnier is, because I didn’t know how to write an outline, unbeknownst to them, I actually wrote a full script and then tried to make an outline out of it. [Laughs.] I wrote the full episode, I sent it to my manager, and I said, “Should I just send this to them?” He said, “No … you get paid on different levels. So send the outline first; you get paid for the outline.” I looked at the scenes in the script and I was like, “Okay, what’s happening? I guess this happens, then this happens, then this happens.” In my outline, there’s a little paragraph for everything that happens.

Noel Bright: We ended up with two scripts and a presentation script. The next step in the process was to interview animation production studios.

Because Tornante doesn’t have its own animation production facilities, a production studio would need to be hired for the job of animating the BoJack presentation, as well as the potential series. Noel and Steve turned to a studio they’d worked with in the past, ShadowMachine (known for producing Robot Chicken).

Alex Bulkley [ShadowMachine]: When Noel and Steve sent over the BoJack script we had an immediate and visceral reaction to the material. It took a whole five seconds to call Noel back and say, “We’re in!”

Corey Campodonico [ShadowMachine]: Very few projects make such a strong first impression. We knew we needed to bring in a strong director that would build on the visual language that Lisa and Raphael had honed together over the years.

Alex Bulkley: We interviewed a bunch of directors to take on the pilot with us, but none of them could mimic a slide-whistle like Hollingsworth.

Lisa Hanawalt: I remember when we were working on the presentation, I hadn’t yet met Mike, and we were just on the phone all the time talking about these character designs and backgrounds. Mike taught me how to draw through the backgrounds so that when you pick up a piece of furniture, there’s still background behind it. I would just flatten everything, because I was thinking like an illustrator, not an animator …

Mike Hollingsworth: Yeah, if somebody had to walk behind a couch …

Raphael: I remember the first draft of BoJack’s house —

Lisa Hanawalt: It was drawn just, like, a small apartment.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: Yeah, and we’d be like, “BoJack’s very rich, and this just looks like your house. [Laughs.] Let’s imagine … Look, here’s some pictures of rich people’s houses.”

Noel Bright: After Mike came on board, we arrived at a place where we felt like the show had a unique perspective, was incredibly well written, had the right art, the look, the feel — it all felt right. So it was like, “Okay, now we actually have to make it.” So casting was the next thing.

The BoJack casting approach was to aim high to secure the kind of big-name talent that could achieve dual goals: to deliver funny and dynamic performances, and to help sell the show in the first place.

Linda Lamontagne [casting director]: We just went for really strong actors — comedic and dramatic actors. A lot of people will pigeonhole actors: If you do comedy, you’re strictly comedy; if you do drama you’re strictly dramatic. Casting directors get pigeonholed that way, too. What’s unique about BoJack is that it’s not just comedy — there’s real dramatic moments in there — and you get the best performances out of people. I loved Lisa’s designs. I loved that it was anthropomorphic, I loved that it was different than anything else. And the script was really smart. I knew when I read it that it was going to be a fun thing to cast. It was not that difficult to get people, because of the caliber of the project and the people involved. Michael Eisner’s name really goes far. I got great responses from agents and managers and talent.

Will Arnett [voice of BoJack Horseman]: I knew Raph was funny the moment I read the first pilot presentation. It wasn’t until we were a few episodes in that I realized just how deep he was prepared to dive.

Aaron Paul [voice of Todd Chavez]: From what I remember, I was presented with a seven- or nine-page written spec treatment. I didn’t see any animation for it; I just heard sort of the broad strokes of what the show was about. And I read it, and I loved it, instantly, of course. The world, the setting, you know? In Hollywood, in the industry, where animals and humans co-exist, and there’s nothing weird about it. It’s just how it is. And I read it and I thought it was just so smart. Raphael explained to me that he wanted to not only do a cartoon that was funny, but also a cartoon that was incredibly tragic at times. I thought that was such a brave, cool idea.

Noel Bright: I love how Raphael tells the story about how the casting went: “Can we get this person?” “Sure!” “Wait — we really can get that person?” And then, all of a sudden, “Yeah, that person just said yes.”

Steven A. Cohen: Well, one casting story we always point to is the line Raphael had written in the script was that there was “a Keith Olbermann type” for Tom Jumbo-Grumbo.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: “Keith Olbermann whale,” which is what I think the script described it as. It was just trying to describe the character!

Steven A. Cohen: Right. We didn’t think he was going to be Keith Olbermann.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: Linda said, “Let’s get Keith Olbermann! We can do it!” And then we recorded him and we did all the lines, and afterward we just said, “Okay, now can we just get some whale noises from you?” And this is in New York; he’s over the phone, and he says, “Mmmmmmwrrrrwrwrwwrwr!” [whale noise] and it’s like, “That’s Keith Olbermann! Making whale noises for our dumb little cartoon!”

Mike Hollingsworth: We were like, “Can you make a noise like you’re spraying water out of the back of your head?”

The final presentation cast featured three of the main actors that continued on into the series: Will Arnett as BoJack Horseman, Aaron Paul as Todd Chavez, and Amy Sedaris as Princess Carolyn. When the series went into production, Alison Brie was cast as Diane Nguyen and Paul F. Tompkins as Mr. Peanutbutter, completing the impressive ensemble.

Noel Bright: For each actor, really we were just offering, “Come in and do this for us,” because we didn’t know where we were selling the show. Netflix wasn’t even a buyer at that point. But in the middle of making the presentation, they announced House of Cards. Once we came through the presentation phase, I remember Steve and I wondering, “Is it going to be hard to convince Raphael that we think we should be taking this to Netflix?” Going into our pitch, we knew that we would only be their seventh original series; so much was unknown about their model of serialized content that, at that time, it seemed like an unnatural place to go.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: By the time we were ready to pitch BoJack, House of Cards season one, Orange Is the New Black, and Arrested Development season four had all come out, and so Netflix felt like a real company doing good stuff. But it was interesting: The different places that we went to affected the pitch. With Netflix, I pitched it as a Netflix show. I talked about how serialized it was going to be and how it was gradually going to change over the course of the first season, which is not something I was vocal about on pitches to other networks. Different places got different versions of the pitch. I ultimately think that the Netflix version was the best possible version it could have been.

Mike Hollingsworth: I remember when you pitched it to Animal Planet you really played up the animal aspects. [Laughs.]

Noel Bright: So we had the show, we had the presentation, we had all the elements so that you feel like you’ve gotten it — everybody felt we were ready. The hard part was selling it. Part of it was that we had to wait a while because Raphael was working in New York again. We had to wait and find that window when he was done.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: I got hired on a show in New York called Us & Them. So I moved back to New York. The show got canceled before it even aired. As soon as I heard the news, I booked a flight back to L.A. and pitched BoJack to Netflix. This was October 2013.

Noel Bright: We had a few things going for us at Netflix at the time, which was just an insane coincidence. Number one, we had cast Will Arnett and Aaron Paul. Both of them were the leads in two of Netflix’s most high-profile shows [Arrested Development and Breaking Bad].

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: At the time they were still taking credit for the popularity of Breaking Bad. [Laughs.]

Noel Bright: Yeah, that’s right — they were open about it. That was their most-watched show at the time. So we had Aaron and Will, who were the first people aboard the project and who also were so passionate about it that, at the outset, we talked about them becoming producers, to help in the sales process. They were great.

Initially, we could not get Netflix to look at the show because they weren’t buying animation. The feeling was once they said yes to an animated pitch, then they’d have to hear a pitch from every other animation producer in town — and they weren’t set up for that; they were still really so new that it wasn’t their focus. We were very lucky that a personal connection led us to a new executive at Netflix named Blair Fetter. Every project needs a champion, and Blair very quickly became ours. Even though Netflix was just ramping up their efforts in original series and not really interested in pursuing animation, Blair still agreed to watch the pilot presentation.

Blair Fetter [Netflix]: The proof-of-concept presentation Raphael created with Tornante was undeniably funny. It felt like I had that video playing on a loop in my office for weeks after. I was dying to meet the guy that created it. Even his name [Bob-Waksberg] made me laugh.

Noel Bright: A few days later he called to tell us that their creative team — which at the time was Cindy Holland, Peter Friedlander, and Kris Henigman — thought it was really great and asked if we had a full-season pitch to present them. Blair had just met with the creative team from Bloodline and was blown away by their level of detail in presenting episode ideas and character arcs for multiple seasons. We passed this intel on to Raphael, who had always envisioned BoJack as a serialized show with long character arcs.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: Noel and Steve had heard that they pitched all three seasons of Bloodline in that first meeting — the full arcs of the first three seasons! So it was like, “Do kind of something like that.” [Laughs.] I was like, “Guys, I know I have the first season — should I have a second and third season ready to start, too?

Steven A. Cohen: Raphael sat at a table with no notes and walked the executives at Netflix through all 12 episodes, for over an hour, in incredible detail. One episode at a time. Not just the thumbnails, but the A, B, and C stories, when there were any.

Cindy Holland [Netflix]: Raphael is a masterful storyteller and his passion for, and command of, the story he wanted to tell was infectious. This was not going to be a typical animated series — this was an at-once silly and serious exploration of what makes us human (and horse, etc.). About halfway through the pitch we were hooked, and we knew we could find an audience who would love this story.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: Every episode had a B and C story at this pitch! [Laughs.] I said, “Here’s episode one, here’s episode two,” and all the way through, I was kind of showing what the scope of the season would be and how it was going to change. The pitch was that we were going to start with a wacky goofy cartoon show and it was going to start getting darker and darker so it becomes like a Girls or a Louie or even a Mad Men — those are the examples I pulled in the meeting to show what I wanted to do with it.

Noel Bright: Raphael skipped over the fact that you only get one shot to be in that room and to have that chance. And he’s underselling it — there were four Netflix executives in that room (Cindy, Peter, Blair, and Kris) who all had to be sure that our team could deliver a great series. Talk about pressure …

Aaron Paul: I am dear friends with Peter Friedlander. After the pitch, I called him up and just expressed my love and passion for this project. And you know, they didn’t buy it in the room, or even that night when I was speaking to him on the phone. But we all knew it was just such a love fest, the moment that pitch was done.

Raphael’s in-depth pitch was thorough and convincing, and with the strength of the all-star cast’s passion for the project, and the presentation pilot, the package was enough to sell Netflix. With one condition.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: In a follow-up meeting they said, “Can you have the series ready this summer?” We said, “Well, I dunno, this summer?” … And they said, “This summer or we don’t want it.” Basically. [Laughs.] So we said [singsongy], “We sure caaAAaan!” We got back and were like, “Hey guys …” and Mike was like, “YOU PROMISED THEM WHAT?!”

Alex Bulkley: I’ll never forget the moment, standing outside the studio on the sidewalk with Noel, contemplating a 35-week schedule to produce 12 half-hours.

Cindy Holland: When I think about BoJack, I think summer — doesn’t everyone? We wanted to give the series its own time to shine and thought keeping it out of the crowded fall network schedule would be best. We knew it was ambitious, but we believed in the team and they rose to the occasion.

Corey Campodonico: The season-one production margin for error was razor thin and is a testament to how organized and decisive the entire team was in getting the show up on its feet.

Lisa Hanawalt: I had to come out to L.A. for a funeral, really sadly, for family, and I got the news that BoJack sold while I was at the funeral, and then I had to go straight to work here before going back to New York to collect my things. I worked here for a couple of weeks, stayed at Airbnbs. It was a really crazy time. I had never done anything like this before. I had been working by myself, completely solo freelance, and then suddenly I had to work in an office with meetings, and I had to stand in front of the character designers and be like [dopey voice], “So this is, uh, my aesthetic, and uh, this is the kind of stuff I like, and let’s make the clouds purple, and uh …”

Mike Hollingsworth: We put one of Lisa’s books, My Dirty Dumb Eyes, on the server, and it was mandatory reading.

Lisa Hanawalt: I don’t think anyone looked at it. They didn’t have time. We didn’t even have time to hire people. We just basically rolled people off of another show at ShadowMachine onto ours.

Noel Bright: We had to be lining up the show even though we hadn’t quite gotten the official green light yet on paper. Raphael had to start writing.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: We had the first two episodes written, and I started writing the third episode without a staff, thinking, “Well, all right, let’s get ready.” Then we started building a writing staff. We had a table read that first week; we didn’t have any of the prep time that you normally have.

Noel Bright: We had a week of prep. We had the writers come in, and we told every writer we wanted to hire that they might work every day of the week, weekends, late nights, and that they wouldn’t get the holidays off, because we started right after Thanksgiving. It was a schedule built around working through the holidays because the start day was effectively the first week of December, and we had to deliver the show in July 2014. All 12 episodes, in nine different languages. [Laughs.]

Raphael Bob-Waksberg: It had to happen. We signed the thing! I mean, it was always clear to me that the work was going to get done, but it was like, “How miserable are we going to be?”

Lisa Hanawalt: And was it going to be good?

Mike Hollingsworth: We wanted it to be the best possible quality, so it was like, “What is going to be the end result of this crunch?”

Noel Bright: We set up a process. It was crazy, and way too fast, and not an ideal situation, but the one silver lining in it was — a lot of times, when you’re doing a pilot, you just have to make decisions, and usually maybe you get them right half the time. Every decision we made had to be made quickly and it was instinctual — there was no time to second-guess it.

Raphael Bob-Wakberg: It’s so funny that we spent two-and-a-half years to make 15 minutes, and then seven months to make the additional eleven-and-a-half episodes.

Lisa Hanawalt: I’m so glad we made the presentation episode because we solved a lot of problems in it.

Raphael Bob-Wakberg: We would have been screwed if we hadn’t done that.

Noel Bright: Initially, when we started series production, I kept saying, “Well, we have 12 minutes, at least, done. So we can reuse that.”

Lisa Hanawalt: Yeah, you didn’t know we had to redo it.

Noel Bright: A couple weeks in they were like, “Oh yeah, we need to redo all of that.”

Lisa Hanawalt: We had to change Todd.

Noel Bright: I haven’t watched the presentation in probably two years, but even back then it was really weird to see the old Todd.

Lisa Hanawalt: He’s ugly. [Laughs.]

With little to no stopping, the bustling studio worked for seven months to crank out the premier season in time to release all 12 episodes simultaneously for streaming. The culmination of more than three years of talking, writing, drawing, and animating saw Raphael’s “Depressed Talking Horse” become BoJack Horseman at the stroke of midnight on August 22, 2014, when the series went live.

Aaron Paul: When we first premiered, people didn’t understand what they were getting. And so I think a lot of critics maybe didn’t even finish the season, because they were like, “What is this?” I thought the first season was brilliant, and I’m a tough critic on myself: If I don’t like something, and I’m a part of it, I will say that it’s terrible. I thought that the first season was really special. But it just didn’t perform all that well in the critics’ eyes.

Paul F. Tompkins [voice of Mr. Peanutbutter]: It found an even bigger audience in the second season and then the critics started understanding that, oh, this is not what we thought it was. I think it’s a really wonderful lesson not only for the people who create stuff but also for the people who consume stuff: There might be more to something than you thought there was. Raphael could have made that show just a funny cartoon for grown-ups, and it probably would have been fine. But I just think the fact that he challenged people’s perceptions and did it the way that he did it was very courageous. Because he must have known, “People might check out of this. If I save this turn until the third episode, people might not get there.” But the fact that you are rewarded for hanging in there and giving the show the benefit of the doubt — because when that turn happens it’s so sharp — I think is a terrific thing.

Aaron Paul: Ever since that first season, it’s kind of been a critical darling, in a way. But it’s all the same show. I think a lot of people just didn’t understand, or went, “Well, this isn’t funny. It’s kind of funny […] And then why am I feeling bad about myself right now? What’s happening?” [Laughs.] You know?

Alison Brie [voice of Diane Nguyen]: I was struck by how smart, funny, and moving the show was. It was the most honest portrayal of loneliness in Hollywood that I’d ever seen.

Aaron Paul: When we first aired, I got an email from Rian Johnson [director, Star Wars: The Last Jedi, Breaking Bad, Looper, Brick] saying, “I just finished BoJack Horseman season one for the second time, and I had no idea that I would cry so much watching a cartoon on television.” And then we actually ended up getting him a role on the show [Bryan, an improv-troupe member from season two]. He just had to be a part of it. People’s reactions are just so great. People are really getting personally affected by this cartoon.

Michael Eisner: Who knew Raphael Bob-Waksberg would deliver a brilliant, clever, funny, and emotional script, with the brilliant series to follow? That kind of talent shows up about once a decade.