How big a star was Burt Reynolds? Consider this: In 1972, Signet published Hot Line: The Letters I Get  And Write!, a collection of Reynoldss fan mail accompanied by Reynoldss humorous responses. (A sample: I could just eat you right up. All of you. I think you should stick to your regular diet, honey. You just know anything as sweet as I am has to be fattening.) Photos of Reynolds fill out the book. In some, hes draped in beautiful women. In others, hes barely clothed, including a shot of him reaching reaching up for a football while wearing only a football jersey, Winnie-the-Pooh style. It ought to have been obnoxious, this big, macho, ridiculously handsome man publishing a book essentially celebrating how every woman in the world wanted to sleep with him. But, at the height of his stardom, Reynoldss charm had a way of short-circuiting offense. Who could stay mad at a guy who could grin like that?

1972 was a kind of annus mirabilis for Reynolds. HeÔÇÖd been a frequent presence in movies and on TV (most prominently on Gunsmoke) without quite breaking through. But he was charming on talk shows, which raised his profile, and had a much-publicized romance with Dinah Shore, which raised it even more. Then came a nude centerfold for Cosmopolitan in April, followed by John BoormanÔÇÖs Deliverance in July ÔÇö and from there, there was no looking back. The year made him the biggest star in America and heÔÇÖd stay that way, at least for a while. With ReynoldsÔÇÖs passing at the age of 82, weÔÇÖve selected a few key film roles, the ups of an up-and-down career that capture what made him such a singular presence.

Navajo Joe (1966)

The 1960s opened up a new path to stardom for those willing to spend a few months overseas. ReynoldsÔÇÖs pal Clint Eastwood couldnÔÇÖt quite crack American movies and instead became a star via Sergio LeoneÔÇÖs spaghetti western A Fistful of Dollars. But not everyone got to work with Sergio Leone. Reynolds wound up working with Django director Sergio Corbucci, who had LeoneÔÇÖs taste for violence but favored a more blunt, brutal approach. Stardom would have to wait a few years, as the movie didnÔÇÖt take off. But itÔÇÖs a solid example of the spaghetti western that captures ReynoldsÔÇÖs youthful magnetism (though his speaking voice belongs to another actor). ItÔÇÖs also the rare western, spaghetti or otherwise, with a Native American hero. Reynolds claimed Cherokee heritage and had played a ÔÇ£half breedÔÇØ on Gunsmoke, and though the filmÔÇÖs depiction of Navajo life is inaccurate, it at least gets some points for having its heart in the right place. (The Ennio Morricone score is one of the best of his western work, too.)

Deliverance (1972)

In retrospect, it seems a bit strange that John BoormanÔÇÖs terrifying adaptation of a James Dickey novel about four men from the city who get more than they bargained for on a weekend canoeing trip would be the film to make Reynolds a star. Not only is it a tough, unsettling watch that finds our heroes menaced (and worse) by the locals in the remote Georgia wilderness, it also puts his characterÔÇÖs alpha male posturing to the test and finds it wanting. ItÔÇÖs almost as if Reynolds was critiquing some of the macho roles heÔÇÖd go on to play before he played them. (He even let the receding hairline heÔÇÖd hide in almost every other movie show.) ItÔÇÖs undoubtedly one of his best performances, showing just how good he could be given the right material ÔÇö when he chose to pursue it.

White Lightning (1973)

Reynolds shored up his stardom with movie after movie that found him driving fast cars, throwing punches, and bedding women throughout the South. The bare-knuckled revenge thriller White Lightning is one of the best of the type, pitting Reynolds against Ned Beatty, one of his Deliverance co-stars, as the crooked sheriff on whom ReynoldsÔÇÖs Gator McKlusky must exact vengeance. Reynolds, who enjoyed doing his own stunts, often seemed to have no higher aspiration than making movies best appreciated after a beer or two. This falls firmly into that category. He followed it up with a sequel, Gator, in 1976; one of several films he directed.

The Longest Yard (1974)

Reynolds attended Florida State on a football scholarship, making him a natural to star in this film about an imprisoned NFL star charged with assembling a team of prisoners to take on a team of guards. Directed by Robert Aldrich (Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, The Dirty Dozen), itÔÇÖs part tough prison-drama, part misfit sports comedy, and ReynoldsÔÇÖs performance as a burnout who rediscovers the joy of the game ÔÇö whipping his teammates into shape while matching wits with a sadistic warden played by Eddie Albert ÔÇö helps balance those two tones. ItÔÇÖs also a quintessential ÔÇÿ70s film, featuring heroes who win just by standing up to an unfair system. (Reynolds returned to play a different role in the 2005 remake starring Adam Sandler.)

Semi-Tough (1977)

In another, different sort of football comedy, Reynolds plays Billy Clyde Puckett, an NFL star who shares an apartment with two lifelong friends: a teammate played by Kris Kristofferson and the team ownerÔÇÖs daughter, played by Jill Clayburgh. The three self-described best friends mean so much to each other they canÔÇÖt even admit theyÔÇÖre in a love triangle until itÔÇÖs too late. Michael RitchieÔÇÖs follow-up to The Bad News Bears brings the same kind of wooly, foul-mouthed comedy to the world of grown-ups in a rambling comedy thatÔÇÖs short on plot but long on shaggy charm (and on jokes about est and other ÔÇÿ70s-born New Age phenomena). Reynolds constantly chews gum and cracks wise in a film that captures much of what made him such a winning presence, but he also conveys a yearning beneath the swagger, playing a character whoÔÇÖs begun to wonder what lies beyond ÔÇ£fucking and football,ÔÇØ the only pursuits that have mattered to him until now.

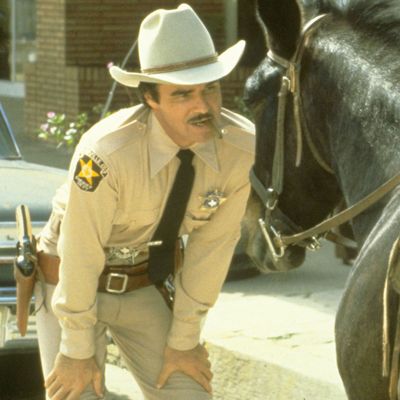

Smokey and the Bandit (1977)

Reynolds scored one of his biggest hits with this story of a trucker who bends the law to bring a truck of Coors beer east of the Mississippi for a pair of wealthy Texans willing to pay handsomely. ItÔÇÖs as thin as premises get, but Reynolds looks like heÔÇÖs having the time of his life as he eludes Jackie GleasonÔÇÖs buffoonish Sheriff Buford T. Justice, pals around with frequent co-star Jerry Reed, and romances Sally Field. The two became an item and co-starred in several more films together. Reynolds had an even longer professional relationship with Smokey and the Bandit director Hal Needham, a stuntman and stunt coordinator who graduated to directing with this movie and would helm six more Reynolds movies, including a Smokey sequel and a pair of Cannonball Run films. Low on ambition and high on charm, itÔÇÖs fun to watch and, from all appearances, was fun to make. Maybe too fun. Reynolds would find these sorts of cars-and-gals-and-yuks movies seductive at his own peril. He famously turned down the Jack Nicholson part in Terms of Endearment to make Stroker Ace with Needham, future wife Loni Anderson, and pal Jim Nabors. He kept enjoying himself even when others didnÔÇÖt.

Starting Over (1979)

Reynolds reduced his trademark smile to a wry, hurt grimace and dialed his sense of confidence way back to play a man shocked to find himself splitting with his wife (Candice Bergen) and forced to make a new life for himself, in this 1979 comedy directed by Alan J. Pakula from a screenplay by James L. Brooks (his first). ItÔÇÖs another example of how he could hold onto his innate appeal while venturing outside his comfort zone to play a shattered man who starts to pick up the pieces with the help of a similarly distrustful pre-school teacher (Jill Clayburgh). ItÔÇÖs a quiet, sensitive film set in a snowy Boston far removed from the backwoods highways that had come to seem like ReynoldsÔÇÖs natural onscreen home. Clayburgh and Bergen earned Oscar nominations for their work. Reynolds did not. The next year he made Smokey and the Bandit II.

The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas (1982)

Reynolds couldnÔÇÖt sing all that well, but he rightly saw this musical about a Texas sheriff whoÔÇÖs come to look the other way regarding a local house of ill repute in part because heÔÇÖs fallen for its madam (Dolly Parton) as a good fit anyway. Though he was apparently not always the easiest person to work with ÔÇö Reynolds and Parton had ÔÇ£sensitive timesÔÇØ during the shoot and he clashed with directors of other movies ÔÇö Reynolds conveyed a preternatural sense of relaxation onscreen. Here, heÔÇÖs charmingly easygoing, playing a man whoÔÇÖs good at his job even if he never has to work that hard at it. But when he is called into action by a hypocritical investigative reporter played by Dom DeLuise (another frequent co-star), he makes sure he gets the job done. ItÔÇÖs not ReynoldsÔÇÖs best movie or his most revelatory performance, but it captures the essence of what made him so appealing: You could kick back and relax ÔÇö maybe even marry ÔÇö this sort of guy while also being sure heÔÇÖd have your back in a jam.

Boogie Nights (1997)

ReynoldsÔÇÖs questionable taste and difficult reputation started to catch up with him in the back half of the ÔÇÿ80s, leading him to take a role in the sitcom Evening Shade, a low-key hit during its four-season run. When it ended, there was already something of a Reynolds renaissance brewing in the mid-ÔÇÿ90s, thanks to high-profile supporting turns in films like Citizen Ruth and Striptease. But Reynolds got the second-act role of a lifetime when Paul Thomas Anderson cast him as porn producer Jack Horner in Boogie Nights. Though it wasnÔÇÖt an easy collaboration, Anderson draws out one of ReynoldsÔÇÖs best performances, one that suggests a sense of dissatisfaction beneath his trademark calm exterior. Reynolds plays him as an artist whoÔÇÖs never quite been able to fulfill his creative ambitions, one now staring at the far end of middle age and struggling to keep up with changing times. Any resemblance to where Reynolds was in his own life was probably coincidental, but helped make the role more resonant. This should have been the beginning of a bold new phase in ReynoldsÔÇÖs career. It wasnÔÇÖt. Reynolds worked steadily for the rest of his life, but through some combination of bad choices or bad luck, struggled to find a part as memorable. But he leaves behind a body of work that proves when he got it right, there was nobody who could command the screen so easily, with a movie-star swagger that demanded attention, a grin that invited you not to take him all that seriously, and a restless glint that hinted there was more to him than either the swagger or the grin could convey.