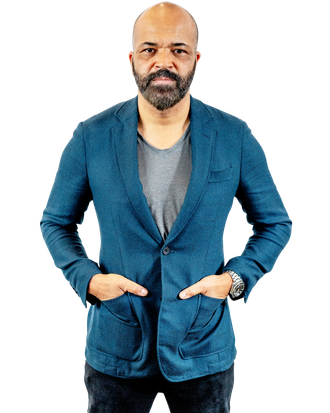

With his expressive eyes and velvety, stentorian voice, Jeffrey Wright seems like a man destined for life as a thespian. He began his career as a performer treading the boards, but recent years have seen Wright branch out from the proscenium and the art house to explore all avenues of entertainment. He’s lent his gravitas to a pair of James Bond movies and a few Hunger Games installments, portrayed Colin Powell and Muddy Waters, kibitzed with vampires and tangled with robots. After collecting an Emmy and Tony for his virtuosic turn as the nurse Belize in Angels in America, Wright has become an awards fixture once again as the supporting player turned lead acts circles around his castmates on Westworld. His latest project gets him in the Netflix game and locates a rare tract of uncharted territory in a widely varied career, casting the distinguished Wright in the grizzled mold of a stone-faced action hero.

Hold the Dark, the latest and most audacious feature from Blue Ruin and Green Room director Jeremy Saulnier, gets in gear when Wright’s character Russell Core arrives in a secluded Alaskan town. A semi-renowned authority on wolf hunting, he’s been summoned by grieving mother Medora (Riley Keough) to recover the son she claims has been snatched up by apex predators before her husband (Alexander Skarsgård) returns from a tour of duty in the Middle East. The pursuit for the boy takes several wrong turns into shocking violence, ultimately leading to a serial killer and a long trail of corpses. A mystical, celestial energy mingles with evil lurking in the hearts of man to form a grim piece of work that left Wright completely fried. In a conversation with Vulture at New York’s Crosby Street Hotel, the actor talked about the draining experience of making the film, changing up the racial dynamics from the original novel, popping up in Game Night, and his bond with David Bowie.

There’s a specific, unified style of acting among the cast of Hold the Dark that’s kind of affected, not necessarily naturalistic. What direction did you get to steer you toward this register?

The acting has been clearly shaped by [director] Jeremy [Saulnier]’s style of filmmaking. The specificity of his frame, the tone, it’s self-evident in the script. It’s a quiet film about a quiet place. It’s sparse, both in the language and the efficiency of the storytelling. I found myself appreciating the structure of Macon [Blair]’s script and bringing that into my performance. You can feel the larger story being played out with each individual scene, feel the bonds tying them together and the momentum of the drama, it’s all infused in each scene. For example, my first scene, where my character reads the letter from Medora on the plane, there’s so much packed in there. That’s the whole film, for me: a guy, simply reading a letter, then turning out the light, and going to sleep.

There are pure thriller elements to this film, then some horror bits near the tail end, and it all resembles a Western structurally. In what terms did you think about genre during shooting?

I thought about it on its own terms, which is partially Western in that it exists within a lawless space where the rule of nature has taken over. Elemental forces play a big role, that’s Western. But you’re right, it’s an adventure–murder mystery–thriller with contemporary Western undertones, and then horror starts creaking out in the woods. It has everything, so in all honesty, I didn’t think about it in terms of genres. As genre goes, it’s for those who love extremely frightening roller coasters, that have all the twists and the steepest drops.

Watching the film is an unrelenting sort of experience, as each scene just keeps building and building in intensity. During production, did any sequences really put you through the wringer?

The culminating scene between my character, Core, and the Sloanes. The last day of shooting included parts of that scene, and at that time, I was arriving at the end of a journey. I was worn out, physically and mentally. We were up in the cold every day, hiking through these muscular mountains. I had gone straight from the end of Westworld’s first season right through three movies after that, and only then on to do Hold the Dark. By the end of production, I was feeling beat up like an old dog, which turned out to be fitting. That scene is so dense with symbolism, every move you make is loaded. There’s more going on than meets the eye to this guy who’s on his last legs, which I felt in that moment.

You’ve spoken about reading the book on which the film is based; what do you think has been gained in the translation from the page to the screen?

Macon captured the descriptive, lyrical qualities of the novel with his dialogue, getting that icy sparseness I mentioned before. At the same time, that language is informed by mythical elements and regionalisms, it’s a very complex mix. The other big shift from the novel is that — well, I play Russell Core. In a positive way, that strips away some of the colonial implications this character might have. Russell’s a true outsider in this community, existing in a world where he has no connection to the native, indigenous culture or the white population laying claim to the land. He’s a different type of outsider. The Sloanes consider themselves to be on the outside, but they have a familial tie to this place. The native peoples have been made to feel like outsiders, but they have more of a claim than anyone. When he’s me, Core can be truly placeless.

You showed up very briefly for a one-scene role in Game Night, and went uncredited. Is there a story there?

They just called me up and asked me if I wanted to come pretend to be a bad actor! Which, I’ve had those days. But it was fun to do a comedy in the midst of all this very serious, heavy stuff that I’ve been up to lately. I’d like to do more, but I’ll tell you what, it’s reeeeeally hard. You know what they say, that dying is easy but comedy is hard? That’s true. It’s so hard. Comedy’s all math, figuring out the timing. I came out to do that scene and I had all these props, the badge and the glasses and the “dossier” and all this stuff, and I realized, oh, shit. I went back to my trailer and spent my entire lunch break mapping out exactly how I would use these props, each and every move.

I saw that Julian Schnabel’s doing a new film about Van Gogh, which reminded me of the Jean-Michel Basquiat biopic you did together. I’ve always been curious — what was your relationship with David Bowie like?

The morning that I found that he had passed, I cried like a baby. He was many things to many people, and so much to me. The primary thing that came to my mind was his generosity. He was an incredibly open spirit. I wrote a little something on Instagram about him, and even doing that, I soaked my phone in tears while I was trying to tap out the words. We stayed in touch after shooting Basquiat and I would see him from time to time. That period, doing Angels in America in ’94 and then filming with Basquiat in ’95, those were gateway years for me as an artist. Two gateways, one into the film industry and one into the world of theater, each formative to me in different, equally essential ways. And so at the beginning of this artistic journey, David Bowie’s there, he’s the guy opening this gate.

Of course, his music is one of the greatest manmade creations of all time. It’s funny — when I was working on Westworld, the woman doing makeup on set had also been the makeup artist on Basquiat, Jen Aspinall. She came up to me one day at lunch and said, “Jeffrey, have you heard from David recently?” I told her I hadn’t, and she said, “I keep having dreams that he’s not well.” That was August or September of 2015. When we wrapped, I took the red eye home and got back to my place in the morning, and my neighbor spotted me coming in. He and I are friends, and he’s an editor, so he wanted me to come see something he was working on. He casually showed me the first cut of Lazarus, and I’m going, “Holy— is this even real?” I remember, I was joking at the time, but I said, “He’s not going out without a fight.” I didn’t think the video was so literal, but a month later, he was gone. It was wild, he was sending out these signals that I wasn’t completely aware of. That last album, I mean, who does that? I’m gonna be on the Hawaiian beaches when I’m old. He was still out there, putting out work, singing with his dying breaths. He’s just Bowie. That’s it.