When Jonah Hill was 7 years old, his parents asked him what he wanted to do when he grew up. He told them, “I want to move to Springfield,” the town where the Simpsons live. The Simpsons was Hill’s favorite show, though that’s like saying the Bible was Billy Graham’s favorite book; it undersells the influence somewhat. “I’m not an authority to make this judgment,” Hill says now, “but to me The Simpsons is hands down the greatest comedy writing ever to exist.” After he’d answered their question, his parents, who lived in L.A. and were both showbiz-adjacent — his mother as a stylist and his father as the accountant for, among others, Guns N’ Roses — gently explained that Springfield was not a real place. Then they broke show business down to two essential career paths: “There’s people who write what Homer says and people who say what Homer says.” Seven-year-old Jonah thought about this, then replied, “Okay, that’s what I want to do. I want to write what Homer says. I want to write Homer’s thoughts.”

And he did — between the ages of 7 and 16, he wrote “a tremendous amount” of Simpsons scripts and kept them in a pile. The quiet creativity of it made him happy, just sitting alone imagining a conversation between Marge and Bart. He was at the same time “the funniest person in every room,” according to his sister, Beanie Feldstein, who’s nine years younger. He was also high-school friends with Jake Hoffman, Dustin’s son, which led to a meeting with Dustin, which led to an audition for Hill’s first screen role, a small part in David O. Russell’s I Heart Huckabees. At 21, Hill appeared in a brief cameo in Judd Apatow’s The 40-Year-Old Virgin, in a memorable scene at an eBay store that involves silver platform boots with goldfish in the soles.

Two years later, in 2007, Hill was recruited for the Greek chorus of stoner bros who surround Seth Rogen in Apatow’s Knocked Up, and he starred in the Apatow-produced teen comedy Superbad, written by Rogen and Evan Goldberg. In Superbad, Hill played Seth, a portly, loudmouthed, obnoxious, vaguely manic, and relentlessly funny kid. The film made $170 million worldwide. Hill had gone from being a person who writes what Homer says to a person who says what Homer — or some very Homer-like younger characters — says. He’d become an actor, then he became a star. He was 24 years old.

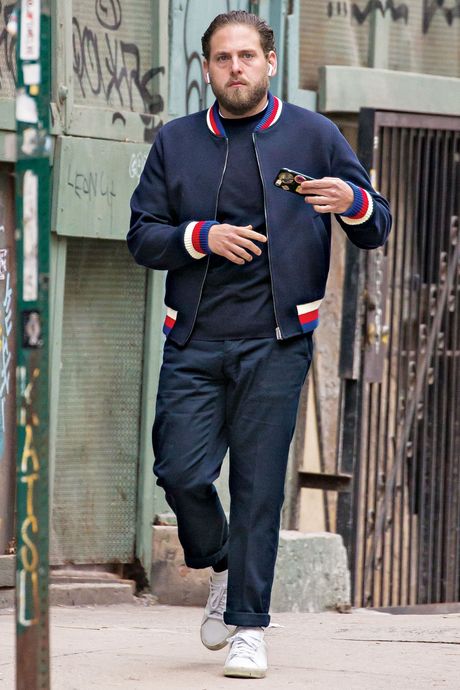

That was over ten years ago, but it’s possible that this version of Hill — the portly, funny, teenagerish, brash comedic actor — is still the one embedded in your head. That’s the kind of thing that happens when you star at 24 in a comedy that makes $170 million. But I should warn you: That version of Jonah Hill is about four versions of Jonah Hill ago. Since then, we’ve met Jonah Hill, Oscar-nominated actor (for Moneyball and The Wolf of Wall Street); Jonah Hill, unlikely style beacon and obsession of Instagram fans, who track his movements and outfits in New York City; and, as of a year ago, Jonah Hill, oddball icon to a pack of acolytes who’ve organized Jonah Hill Day, an annual celebration in Brooklyn. In the past few months, we’ve seemingly seen a new Jonah Hill emerge, like a butterfly from a chrysalis, but with a lot more fresh tattoos. During a recent visit to Jimmy Kimmel Live! to promote the Gus Van Sant film Don’t Worry, He Won’t Get Far on Foot, Hill, in a genial mood, started by addressing the audience: “I’ve been gone for a couple of years. It’s nice to see everybody.” He continued to the viewers, “I met you when I was like 20, and I’m 34 now. I feel like I spent my whole 20s trying to be who people wanted me to be. And I didn’t know who I was. The past couple of years have been amazing in that I’m just going to be myself.” The audience cheered.

Watching that clip, considering all the iterations we’ve seen so far and this surprising new version we’re meeting now, it’s hard not to wonder: Is it possible we’ve never really met Jonah Hill before? He’d like to introduce, or reintroduce, himself. We can start with a phrase that would have seemed hilariously unlikely ten years ago but now seems poignant and possibly important: “Written and directed by Jonah Hill.”

In the Flatiron office of A24, the boutique distribution company behind Mid90s, his debut film, Hill sits in a vast, airy boardroom, wearing chunky black glasses and a well-groomed beard. His bumper crop of new tattoos, acquired during the recent “just going to be myself” period, are hidden by the long sleeves of a casual velour pullover. He’ll show off one, the same he shared with Kimmel. It reads HELLO, BEANIE! in the Hello, Dolly! Font — a tribute to his sister, who appeared in that show on Broadway and also starred in the film Lady Bird. “I did this because I love her,” Hill explains.

“She’s my favorite person in the world and my best friend.” Later I ask Beanie what she thinks about the tattoo. She says she’s flattered: “He told me he was going to get it. I didn’t think it would be so big.”

The walls of the A24 boardroom are empty save for a single poster, for Mid90s, which creates the perhaps inadvertent (or perhaps purposeful) impression that it’s the only Jonah Hill film that matters right now. It features the movie’s star, Sunny Suljic, who was 11 during filming, staring straight into the camera with a slightly defiant look under the tagline “Fall. Get Back Up.” Mid90s is a coming-of-age story set in L.A., so you might expect that it’s strictly autobiographical for Hill, but it’s not. Suljic plays Stevie, a lower-middle-class kid from a rough home, with an abusive older brother and an overtaxed single mom, none of which is true of Hill’s childhood. Mid90s centers on Stevie’s induction into a tight-knit group of rambunctious skateboarders with nicknames like FuckShit and Fourth Grade, so you might expect it echoes the pleasures offered in some of Hill’s early roles, in films like Knocked Up, which were built around the fun of watching a bunch of dudes hang out and roast each other while you get to tag along. But tonally, Mid90s isn’t like that, either — the kids are sweet and funny and caring but also casually cruel and irresponsible and more than willing to put each other into mortal danger. Mid90s owes more to Kids and Harmony Korine than to anything by Apatow.

If Hill learned a lesson from his early success in Superbad, it’s this: “I got to watch Seth and Evan and [director] Greg Mottola make something that was truly what they wanted to make. It was their voice, their ethic, their aesthetic, their emotions.” That planted a seed in him. That seed took ten years to germinate, during which time Hill incidentally became one of the biggest comedy stars in the world. Now he’s made the film that reflects his voice, his ethic, his aesthetic, and his emotions, and it’s the story of a preteen trying to find acceptance and learning how to accept himself. “I wanted to show what it’s like to try and make your way,” Hill says, “and how acceptance happens so gradually or not at all.” He’s been thinking a lot about that — about value and acceptance and the difference between what the world tells you you’re good at versus the things you really want to pursue. This, to him, is what Stevie’s story is all about — not a feel-good tale about falling and getting back up but the story of discovering your true value and how “the things you don’t see about yourself are actually the things you have to offer,” Hill says. Sometimes it takes a while to realize what those things are. He should know. Over the past three years, he would often wonder why he was bothering to write and direct a film. Why do I want to do this? he’d ask himself. But he realized the answer: “Because I want that idea to land.”

Hill started out writing a different movie, about a grown man (with constant flashbacks to his 12-year-old self skateboarding), but when he described that film to the director Spike Jonze, his friend, Jonze told him, “You look uninterested when you’re talking about the main story, and you light up when you’re talking about when they’re skating. That should be what you write about.” (Hill was reticent to share more details on the jettisoned grown-man plotline, since he may yet use that in another script.) Hill wanted to make a film about skateboarding because it meant a lot to him when he was an adolescent, around the same age he was devouring The Simpsons. Skateboarding had an outsider ethic — “a sort of punk, ‘anti’ ethic,” he says, that appealed to him and drew him in. He wasn’t great at skateboarding, himself. “I would say dedication-wise I was 100 percent, but skill-wise 14 percent.” He could do a couple of tricks, but mostly he enjoyed the feeling of community. Hill’s not the first comedian or actor I’ve encountered who has mentioned having a formative relationship with skateboarding. It’s a pursuit that to an outsider can seem like a way for kids to waste endless summer afternoons, sort of like loitering on wheels. But skateboarding mimics the rhythms of creativity. You learn a new trick. You practice until you master it. You show it off. You start again. You move on to the next, harder trick.

This becomes a useful lens through which to consider Hill’s career.

From afar, his acting résumé can seem unpredictable to the point of being haphazard. “He knew the pitfalls of early success, and he was determined to avoid them,” says Scott Rudin, who produced Mid90s. “And he has a prodigious knowledge of show-business rhythms. He’s very astute at watching who the players are in the room and how they’re moving the pieces around the board.” After succeeding in broad comedies, Hill starred in the 2010 off-putting sort-of comedy Cyrus, directed by the Duplass brothers. He then played Peter Brand, a nervous, shuffling brainiac, in Moneyball, opposite Brad Pitt. He co-starred as Donnie Azoff in The Wolf of Wall Street, in a performance that was ferociously comic in the way a riled-up pit bull can be ferociously comic as long as it’s on the other side of the fence. In the upcoming Netflix limited series Maniac, Hill plays Owen Milgrim, a character so timid he threatens to collapse in on himself. His whole acting career thus far has consisted of doing things you didn’t think Jonah Hill could do, then moving on to a new thing. Of learning the next, harder trick.

That’s the acting part. Hill once told Howard Stern, “I think I am pretty good at making movies. I am not good at being a famous person,” and he’s gotten in trouble at times in his celebrity career. In 2014, he shouted a homophobic slur at a particularly persistent paparazzo, then apologized profusely during a week of celebrity penitence. Given that, it’s notable that the kids in Mid90s talk like, well, kids from the mid-’90s: They curse and call each other all kinds of names, including the names Hill himself got in trouble for using. Hill has thought about this; he thought about taking that out. But he wanted to be true to skateboarding culture and the way kids talk, which is partly how he ended up using those words himself. “It’s very deliberate to show how ugly that vernacular was,” he says of the dialogue. To be fair, what these conversations convey in the film is not that these kids are cool but how badly they want to seem cool and how often they fail to pull it off.

Hill has also been seen as prickly. This has been mostly related to his taking offense at such journalistic inquiries as “What kind of a farter are you?” (That is an actual question he’s been asked. He reportedly answered, “I’m not answering that dumb question! I’m not that kind of person! Being in a funny movie doesn’t make me have to answer dumb questions. It has nothing to do with who I am.”) As I talk to him now, he seems like he’s over that kind of thing.

Is he over that kind of thing? There’s a funny moment early in his Kimmel interview when Kimmel says, in a friendly but pointed way, that Hill smells good, “which is surprising.”

“Why is that surprising?” Hill replies. The implication seems obvious — that Hill is a funny and vaguely slovenly dude and not someone you need to take seriously. But then Hill laughs it off. “I’m going to really work hard to not take that as a shot,” he says. He seems to be working really hard to not take things as shots these days.

“You can’t live in a world where you’re wondering what people think of you. It will just drive you crazy,” he says later. This is his constant refrain about life in the public eye: You can’t worry about it. Just do what you’re doing. The rest will sort itself out. Just put one foot in front of the other.

Several incidents in Hill’s recent life may have led to this change in perspective. “Someone close to me,” he says, gave him a copy of the poem “Ithaka,” by C. P. Cavafy, not too long ago, which really moved him. The message, he says, is “it’s the journey, not the destination. I really abide by that.” He tells a story of acting with Joaquin Phoenix, when Hill nailed a particular scene and afterward Phoenix give him a little nod, which to Hill felt great — “like, ‘Respect.’ Like he confirmed it.” Feeling happy, Hill moved on to the next scene and just blew it. “And Joaquin smiles even bigger at me.

He’s like, ‘Whenever you think you have it is exactly when you don’t have it.’ ” That’s Hill’s philosophy now. “I could give you any answer to these questions, but the reality is, I don’t have it. To me, the lesson of life is you never have it. It’s all just starting over every day.”

There’s also a scene in Mid90s in which Ray, a skateboarder played by Na-Kel Smith, tells Stevie a story about losing his younger brother suddenly to a car accident. Smith delivers it with such earnest emotion you initially suspect that maybe it’s drawn from his life. But then, it could have been drawn from Hill’s life, too—his older brother, Jordan Feldstein, a music manager for bands like Maroon 5, died suddenly of a pulmonary thromboembolism at age 40 in 2017. The answer is neither: The scene was written years ago, Hill says. It was always the emotional core of the film. “In regards to my brother, I love him and I miss him very much, and that’s all I want to talk about that.”

Overall, Hill comes across like someone in his early 30s who has just been through the familiar and necessary process of figuring out who he is — but who happened to do it while also becoming, as of 2015, the 28th-highest-paid actor in the world. (A particularly good year for him was 2015, in which he reportedly made $16 million — nearly $10 million for the sequel to 21 Jump Street alone, a project he produced and developed from the start.)

Artistically, he’s now less concerned with how to make millions (for himself or others) than with how to keep the expectation of making millions (for himself or others) from preventing him from making things he really wants to make. He likes working with Rudin and Eli Bush, his producers, and with A24, because there’s not the expectation “to make a bajillion dollars and be so mainstream.” Personally, he seems like someone in a very good place or someone who’s working very hard to convey that he’s in a very good place, and maybe there’s not much difference between the two.

Perhaps the most unforeseen development in his recent life is his emergence as a lifestyle icon. He’s joined Instagram, briefly dyed his hair pink, and got all those new tattoos. He’s become a notorious connoisseur of, and occasional spokesperson for, au courant streetwear brands. While filming The Wolf of Wall Street, he moved to New York, then realized, “Wow, I don’t have to live in L.A. I made a list of my favorite filmmakers, and the majority of them live in New York. I was like, Wow, you can actually just live in New York City!” So now he does. A menswear Twitter feed, Four Pins, started the “Jonah Hill Fit Watch,” which chronicles his style and physical fitness (his weight has famously fluctuated) in a largely affectionate way. Both Esquire and GQ have also praised his fashion choices — Esquire declared he has “the perfect approach to street style,” and GQ called him “our new style savior” — mostly because he walks around New York looking simultaneously as if he cares a little about cool clothes but not very much about the edicts of magazines like Esquire and GQ. A podcast, Failing Upwards, started Jonah Hill Day a year ago to coincide with Fashion Week. “It started as a kind of ironic, tongue-in-cheek thing but from a place of sincerity,” says Lawrence Schlossman, co-host of Failing Upwards. “Here’s this guy a lot of people grew up with as a jokey, overweight class clown in Superbad or This Is the End. Now we’re seeing him transition. He’s successful. He’s credible. He mixes Palace and Prada. He’s like next-level Jonah Hill — an aspirational but attainable avatar.”

The advent of Jonah Hill Day both amused and alarmed Hill. I point out to him that there are two kinds of people in the world: people who would flock to a day named after themselves and people who’d stay very far away. “I’ve been both!” he says. “The first year, I didn’t go because I was too nervous. I was like, Is it arrogant to go? You get so in your head. But then I thought, These people are throwing a day for whatever reason, out of appreciation. I’m going to go show them love.” And so he did. He was amazed, he says, to discover that the attendees weren’t 15-year-old fans, as he’d expected, but mostly grown-up men around his age. He smiled and posed for photos and generally had a good time, even though in some of the photos he’s standing next to a cardboard cutout of himself.

“We call this ‘The Mansion,’” Hill announces the next day, in a darkened editing suite in Tribeca. He’s working on a very last-minute tweak to Mid90s with his editor, Nick Houy, before the film is picture-locked. It’s the tiniest change imaginable: In a shot that flashes by in a montage, we see Stevie and his mom watching a movie on TV; it’s part of their weekly movie night, a sacred ritual. The film, barely visible, is GoodFellas. Hill wants to swap out one GoodFellas scene for another. “Originally, it was the scene where [Joe Pesci] is shooting Spider,” he explains. “But I wanted to go with a less obvious scene. My favorite is where Scorsese’s mom is holding up her painting of a dog. It’s a little more low-key.” Hill understands that literally no one will notice this detail. Still, he had to make it. In part, he wants to show love and respect to Scorsese, and though he knows most people won’t catch it, maybe a few people will. He has loaded the movie with little moments like that: unannounced cameos by favorite rappers or skateboarders and offhand nods to cherished films. “The key is not to make a meal of it,” he says, “but if you know, you know.”

In the early days of editing, Hill and Houy had been working in a smaller, windowless editing suite, but they got moved up by A24 to “the mansion” after an early screening of the film. “I guess they liked the movie!” Hill says, excited. He’s wearing the same black glasses, now with an all-white ensemble: white sweatshirt, white pants, white shoes. (The more streetwear-savvy readers will wonder, What pants? What shoes? I am the wrong correspondent to relay this.) This editing suite, “the mansion,” is not only bigger, but it also has windows, though they’re covered with blackout shades, giving the room a womblike feel. Hill says this is his favorite place to be in the world right now, and it’s easy to believe him. If you had spent your childhood making up Simpsons episodes and then sort of accidentally became an object of fascination for people who snap your photo and post it on the internet so they can talk about your pants, you too might enjoy spending your days in a darkened room, fiddling with your very first film. You too might spend endless hours worrying about the final details of a scene in which a little kid falls in love with watching movies.

For Hill, Mid90s is the culmination of a ten-year, self-directed film school. It is remarkable to look back and realize that, at age 34, Hill has already worked with Scorsese, the Coen brothers, Quentin Tarantino, the Duplass brothers, Gus Van Sant, Bennett Miller, and Cary Joji Fukunaga. On the set of The Wolf of Wall Street, he marveled at Scorsese’s ability to solve, in 30 to 45 seconds, a problem another director might spend an hour on. “But that’s some combination of genius and experience,” Hill says. “It’s so awe-inspiring that you don’t even aspire to it.” It does mean, however, that when you’re finally making your own first movie, you can call up Scorsese for pointers, then drop by his house expecting a 15-minute conversation, as Hill did, and wind up talking for four hours.

Or there’s the time Hill was out for dinner the night before he was to start shooting Mid90s. He ran into Ethan Coen, with whom he’d worked on a small, one-scene role in Hail, Caesar! — a part Hill took specifically so he could watch the Coen brothers work. Hill asked Coen if he had any advice. “Let me think about it,” said Coen. “I’ll find you before you leave.” Later, Coen stopped at Hill’s table. “I’ve got it,” Coen said. “Just try and enjoy it. I was so stressed out during my first movie, I didn’t enjoy anything. Even try to enjoy the stress. Just enjoy the newness of it.”

Tonight, Hill says, once he’s done in the editing suite, he’ll go home and watch the Stanley Kubrick film Barry Lyndon, a favorite of his, for the second time that week. He’s not watching for escape or even enjoyment. He wants to study it. He wants to imagine why Kubrick made every decision he made. He wants to learn.

At his advanced age, Hill now gives a lot of advice to his sister Beanie, who at 25 is more or less at the same point Hill was after Superbad. But the paradox of his own career is that it’s nearly impossible to emulate. So what advice would he give a 20-year-old kid starting out now? “Don’t try and do what you think is flashy or is the coolest thing to do. Think of what you actually love,” Hill says. Okay — so when exactly did that happen for him? When in his career did he figure out what he actually loves?

Hill thinks about this for a long moment in the dark of the editing studio. Then he thinks for another long moment. It doesn’t seem like he can’t recall when this happened. It seems like he’s wondering whether he should reveal it.

Then he says, “When I pulled up to the set on the first day of Mid90s, and the cameras were there, and the trucks were there, and the kids were in their costumes, and I was behind the camera, I thought, This is home. I knew this is what I wanted out of my life.” He could end there. But he doesn’t. “And I didn’t feel like it was given to me. I felt like I had worked for it.”

*This article appears in the September 3, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!