Spoilers below for Better Call Saul season four.

“S’all good, man.”

That is the parting shot of Better Call Saul’s fourth season, as Jimmy McGill (Bob Odenkirk) is led away from his partner Kim Wexler (Rhea Seehorn) to sign papers that will return him to the field. “Good” is a concept that Jimmy’s gotten further away from during the run of the show, and there is nothing good about the way he achieves his victory here. Kim’s reaction to his revelation of insincerity — the same quality that caused a different tribunal to reject him the previous week — is wrenching in part because it stands in for viewers who like Jimmy, and who want to continue to see redeemable qualities along with his amazing facility for con games and improvised bullshit. It’s hard to see Jimmy going the other way between now and the end of this show, whenever that turns out to be. The look on Kim’s face at the end is heartbreaking: deep disappointment shading into nausea at what an empty-hearted manipulator Jimmy has become.

The other characters end the season in morally precarious places, too — Mike (Jonathan Banks) more than anybody, after executing the runaway German engineer Werner Ziegler (Rainer Bock). This is the first killing we’ve seen Mike commit that was cold-blooded — housekeeping with a gun instead of a mop. He was on the gray scale already when we met him, but things are looking a lot darker now. Meanwhile, Mike’s boss, the canny individualist Gus Fring (Giancarlo Esposito), is on the brink of being fully absorbed into the Salamanca empire — I’d rather not say how that story resolves in Breaking Bad, as increasing numbers of people tell me that they’re watching BCS despite never having seen a frame of the other series — and Salamanca captain Nacho Varga (Michael Mando) is facing what looks a purgatorial sentence, somewhat mirroring Jimmy’s season of doing without a law license. He’s forced to deal with a new Salamanca, Eduardo a.k.a. Lalo (Tony Dalton), not long after trying and failing to kill another one (Mark Margolis’s Don Hector, to whom Lalo presents the desk bell that will become his aural signature).

Only Kim seems to have incorporated outlaw tendencies into an otherwise ethical framework, in a way that gives her an edge over opponents without causing irreparable self-inflicted damage to her core of decency. The audacious “Miracle on 34th Street” strategy that she devised to save Jimmy’s right-hand man Huell Babineaux (Lavell Crawford) from jail time, however brilliant as a tactical maneuver, constitutes multiple varieties of fraud. All those phony letters of support that Jimmy hired strangers to write on a cross-country bus, then mailed from Huell’s hometown post office in Louisiana, could come back to haunt Kim in a future season; this series, like Breaking Bad, saves string as diligently as a nest-building bird.

But for now, Kim is still the closest thing Better Call Saul has to a voice of conscience, her attraction to Jimmy an Achilles heel inseparable from her attraction to danger as well as her sentimental attachment to winning seemingly unwinnable cases. The switcheroo that she pulled with the architectural plans for Mesa Verde’s El Paso branch could also get her in trouble, thrilling as it was to team up with Jimmy again in what could’ve been a deleted scene from The Sting. Her hands are dirty for sure, but she hasn’t smeared herself from head to toe in muck like Jimmy, or knowingly slithered deeper into the swamp like Mike. But in one respect, Kim’s position might be the saddest of all, because she gets to watch somebody she cares about and believes in turn colder and more manipulative over time, with no reasonable hope of pulling him back in the other direction.

It’s a gut punch even if you knew that Jimmy McGill had to become Saul, that his corruption would be a subtle process, and that — as on Breaking Bad, the series that created Jimmy/Saul, as well as Mike, Gus, and other BCS regulars — it wouldn’t be the sort you could analyze like a soil sample and then display with each layer named and tagged. Saul was always present in Jimmy, just as Heisenberg was always present in Walter White. To the credit of both shows, the writing, directing, and acting gave you a lot of information to process but tended to stop short of telling you exactly how you were supposed to read it.

None of that numbs the bruising sadness of Better Call Saul’s fourth season finale, the capper to the best and bleakest season of this excellent comedy-drama. This batch of episodes embraced the bifurcated nature of the show, which always spent roughly half of its time in the high-dollar world of white-collar crime and the other half among physically violent drug dealers and street criminals — embraced it so fully, in fact, that it often felt as if we were watching two shows in one, starring three central protagonists (Jimmy, Mike, and Kim) and many major supporting players, all sliding on the moral spectrum between pure and corrupt, each landing farther along by the end.

Series creators Peter Gould and Vince Gilligan and their peerless writing staff (which includes Gennifer Hutchison, Alison Tatlock, Ann Cherkis, Thomas Schnauz, Heather Marion, and Gordon Smith) have created a series that’s nearly immaculate in its construction, with every story beat taking the form of a clearly laid-out montage, sequence, or theater-style scene — one that usually unfolds at a much slower pace than TV’s usual, leaving room for pregnant pauses, entrances and exits, and moments where we get to just stare at a character’s face as they contemplate what they’re about to do, what they’ve just done, or what’s about to happen to them. (The way Werner lets his friend Mike off the hook is devastating in its own way: announcing how much he loved the big night skies of New Mexico, then walking out into the desert for one more look at the stars.)

But at the same time, the show is open-ended in its possible meanings. Viewers with different philosophies of what constitutes good and evil, and of how far a person can go toward the darkness without becoming irredeemably bad, can look at the same dilemmas (like Mike’s distress over Werner’s unruliness, Jimmy’s relentless push to get his law license back, and Kim’s expedient balancing of the bank’s thirst for expansion and her second career as a defense attorney) and come to different conclusions. BCS is also beguiling in how it embraces the smaller, more slowed-down quality of the world it has created, in stark contrast to Breaking Bad’s simmering weekly frenzy of plots and counterplots, shootouts and corpse disposals. The moment in the finale where Mike, trying to shake the pursuing Lalo, reaches into his glove compartment and grabs a pack of gum instead of a pistol is a Steven Spielberg–worthy reversal-of-expectations sight gag — like the moment in Raiders of the Lost Ark where Toht pulls out what we assume is a nunchaku-like torture implement, then folds it into a hanger for his trench coat — but it’s also a summary of this prequel’s working methods. BCS tends to go small instead of big, then pay off the small choice in a way that compensates in cleverness for whatever it lost in noise and scale, as when Mike feeds a foil-wrapped slab of chewed gum into the parking lot ticket machine, trapping his pursuer.

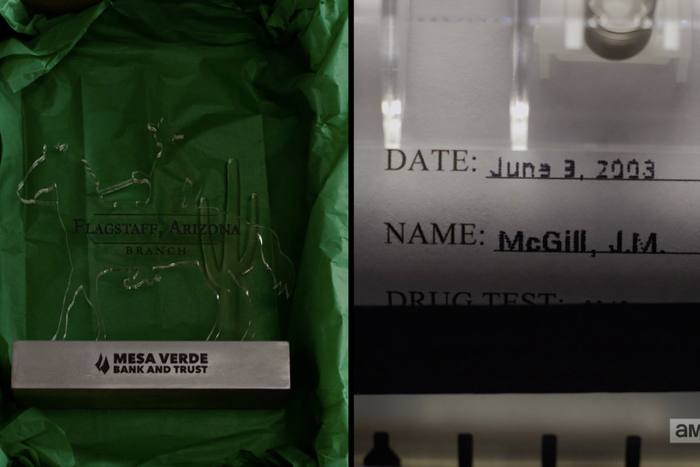

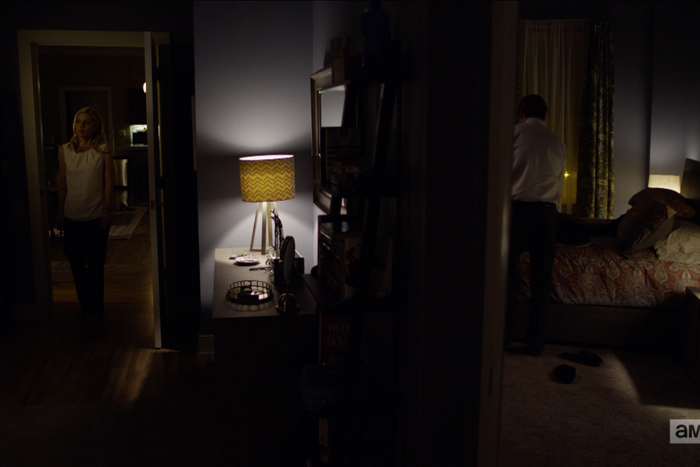

The visuals are consistently as eloquent as the dialogue, and often more withering in their willingness to judge the characters. My favorite is the split-screen montage that opens “Something Stupid” — a montage in the spirit of the dissolution of the hero’s second marriage in Citizen Kane, where Kane and his wife are shown drifting farther apart, their emotional distance reflected by their sitting farther apart at the dining table. Without an audible word passing between Kim and Jimmy, we see the difference in their daily lives — her Mesa Verde desk plaque, juxtaposed with his name on a pee test — and we know that this relationship can’t possibly go the distance. The repeated overhead shots of the two in bed, often arriving at different times and not acknowledging each other, are paid off in a climactic shot of Jimmy in bed without Kim, her half of the frame fading into blackness as if a piece of Jimmy had broken off and fallen away. The split screen also conveys the idea of lives unspooling along parallel roads, connected in theory but not necessarily in fact; or, more accurately, connected to the extent that the characters desire — or are capable of — connection.

By the time we get to what feels like their breakup conversation in the ninth episode, the appropriately titled “Wiedersehen,” the show reminds us of that great montage by dividing the screen into mirror-like halves, using composition to put an implied line down the middle of the frame. Then it puts Jimmy on one side and Kim on the other, most noticeably in a shot that echoes the split screens of Jimmy and Kim in the bathroom together in “Something Stupid.” But here, they’re physically together and emotionally separated. And the reflection of them in the mirror feels faintly mocking, like a painting of a couple that’s not a couple anymore.

What a sad and beautiful show Better Call Saul is. It’s a lament for squandered human potential that’s too cool to ever use a word like “lament,” and a portrait of actions and consequences that goes far beyond simplistic finger wagging, letting us intuit the reasons why people do things — like the reaction shots of Mike regarding Werner as he pleads for his life, or all the scenes of Jimmy in denial about his role in his brother Chuck’s death spiral, refusing to talk about him willingly, and acting as if he means nothing even though he meant everything. “Did you see that one sucker?” Jimmy asks Kim right after the appeal, torpedoing her naïve hope that his statement about his brother came from the heart and not the lizard brain. “That one asshole was crying. He had actual tears!” This series is obsessed with con games and magic tricks, but its greatest sleight-of-hand is dramatic: It lets us laugh at its characters, then it makes us cry for them, too.