Bookseller One Grand Books has asked celebrities to name the ten titles they’d take to a desert island, and they’ve shared the results with Vulture. Below is author of the recently released short-story collection Your Duck Is My Duck Deborah Eisenberg’s list.

Five volumes of sheer bliss. There’s almost nothing fiction can offer that isn’t in this book: an 18th-century, postmodern, Zen, worldly, otherworldly, gorgeous, funny, sorrowful, gripping saga of a large, staggeringly wealthy Qin Dynasty family. Stunningly well translated, (the first three volumes by David Hawkes, the final two by John Minford, Hawkes’s son-in-law). It takes a while (or it did me) to keep the many, many characters straight, but it’s definitely worth the trouble.

Written after the end of WWI, which upended the globe, but set in 1901 in a provincial town where nothing, nothing, nothing at all can change, this enchanting, witty, shattering, profoundly compassionate fable-like short novel seems to contain all the world’s pain in an iridescent soap bubble.

Who can really understand Bowles’s writing? Well, some people can, but not I. Nonetheless I love it, and it has the irrefutable hyperreality of dreams. Only a very few other writers (Denis Johnson is one) have used American English with such exactitude and so cracklingly, have observed so fearlessly the emotional abysses that confront us, and are so deliriously funny. Claire Messud’s introduction to the recent Ecco edition is eloquent and insightful.

Babel is known for the gleaming polish and explosive compression of his work. He was, among other things, a war correspondent, and these stories are confected from his experiences of following the Polish-Soviet War of 1919–1920. They treat, in part, paradoxical relationships between idealism and brutality, between triumph and shame, and in a page and a half he can emblazon on your brain a revelation that no other writer could represent in a thousand pages.

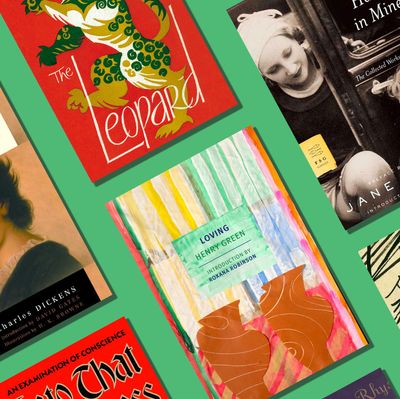

It’s been some years since I’ve read The Leopard, but I’ve read it a few times and it lives in my mind as a perfect thing, glowing and stately — it’s an incomparable experience of communing with a great and generous intellect. Like Cao’s The Story of the Stone, The Leopard concerns an aristocratic family trembling on the brink of change, and like The Story of the Stone, it was published only posthumously. Although both authors died unrecognized, their books became probably the most popular and beloved books of their respective countries.

This just happened to be the one of Green’s novels that floated to the Favorite position in my mind today, but they rotate. Really, in my opinion, these peerlessly eccentric, comparatively short marvels, which are so bafflingly different from each other as well as from everything else, should be considered parts of a whole. Loving is the most visual of them, but each has its own extraordinary qualities.

Virtuosic linked stories, all but one set in Rumania, Austria, or Germany before WWII, whose charming, maddening, light-minded narrator has no particular need to notice that murderous thugs are rising up and closing ranks right in front of his nose. The book is an exceptionally vivid evocation of prewar Central Europe, and it’s also terrifyingly funny in its examination of specious reasoning, casual complicity, and the obtuseness that’s the hallmark of privilege.

Stripped to the bone, as sharp and lucent and alarming as a piece of broken crystal. An Englishwoman who has always depended on men to stay alive is older now and discarded. She has returned to Paris, which is as close as home to her as a place has been, but she no longer retains her one reliable resource, beauty. The intensity of her alienated helplessness renders with spectral clarity her memories and her precarious daily life in the city that no longer wishes to make room for her.

My favorite Dickens. Raucous, caustic, tender and furious, uncontainably abundant. It careens around between every imaginable social class and institution of its contemporary London, including the Office of Circumlocution, which ensures that nothing whatsoever can possibly be done to benefit anyone in dire need. All too recognizable.

How is it possible that Franz Stangl, a kindly, unassuming, mild-mannered family man and policeman from the small Austrian city of Linz became the commandant of the Nazi death camp Treblinka, where he wore white riding breaches to oversee mass murders of Jews? Gitta Sereny conducts her months of interviews of him in prison — as well as interviews with his wife and acquaintances — with her customary decorum, intelligence, and respect. One of her many outstanding strengths as a journalist is that she is entirely committed to understanding her subjects rather than demonstrating that she and her readers are unassailably superior.