“I’ve been misunderstood,” Dolph Lundgren tells me. “I’ve been taken for granted. I’ve suffered: physically because of all the films I had to do; psychologically from my dad, and from people thinking I’m a big, blond thug with no emotions who can’t act.” As he says this, he avoids eye contact. He fidgets with the recorder on the table between us. He shifts his weight back and forth in his seat. He seems eminently vulnerable.

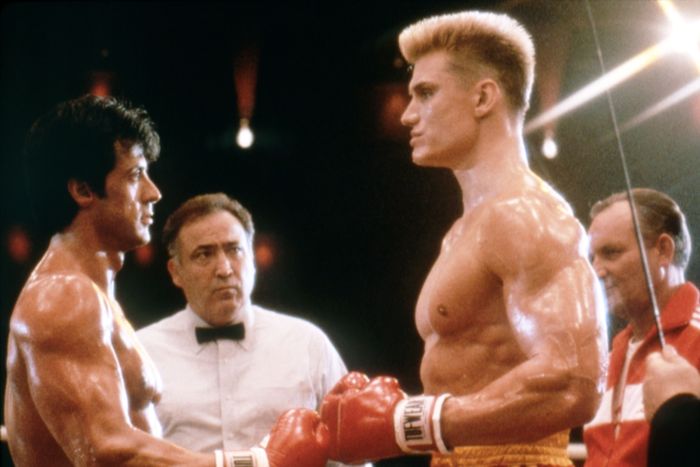

It’s not a mode one expects from this mountain of a man. The 61-year-old is, after all, one of the most prolific and iconic action-movie actors of his generation. He has more than 80 film credits to his name, largely playing warriors and killers. He was He-Man. He was the Punisher. He was an Expendable. But, perhaps most important, he was Ivan Drago, the Soviet pugilist who nearly bested Sylvester Stallone’s title character in 1985’s Rocky IV. In that film, Drago seems cold, bloodthirsty, driven, merciless — anything but vulnerable.

Then again, maybe we just didn’t get to know Drago well enough. We certainly didn’t get to know Lundgren well enough. Ever since his turn as Drago cemented him into celluloid history, people have made assumptions about the actor. They think that he’s Russian, that he’s dumb, that he’s talentless. In actuality, he’s Swedish. And he has a master’s degree in chemical engineering. As for the talent bit, well, that’s in the eye of the beholder. But with roles in two big-deal Hollywood pictures in as many months — Creed II and Aquaman — Lundgren is hoping he can prove to the world that he’s more than a Nordic beast. He’s ready to be one of those former stars who stages a comeback as a dramatic performer in middle age. If he has his way, the Lundgrenaissance will soon be upon us.

He has to convince the world that he’s ready for that kind of career shift, but before that, he had to convince himself. In Creed II, Lundgren returns to the Rocky Cinematic Universe and reprises his role as Drago, a role that has been both his calling card and his burden for more than 30 years. “When I first got the text from Stallone two years ago, he said” — and here Lundgren slips into a perfect Stallone mumble-grumble — “‘Hey, wanna play this guy again?’ And I was like, Oh, shit. Drago.”

Yes, Drago. Rocky IV was only Lundgren’s second acting credit ever, but his performance etched itself into the cultural consciousness and changed his life forever. Just a few years prior to the ’80s classic’s release, even the idea of being in a movie would have seemed completely alien to the man. Born in Sweden in 1957, his father was an engineer and, in Lundgren’s telling, physically and emotionally abusive toward him in his youth. Nonetheless, the boy strove to prove he could succeed in the family business. An accomplished scholar athlete, he studied the sciences in Sweden and the United States throughout his teenage years, then earned his master’s at the University of Sydney and was awarded a Fulbright scholarship to study at MIT.

Then a chance encounter changed everything. While in Sydney, Lundgren worked a side-hustle as a bouncer and one night found himself working a Grace Jones concert. The art-pop legend noticed the towering, almost unsettlingly handsome Lundgren and invited him to spend the night with her. He eagerly complied, and the two were soon an item. She suggested that he decamp to New York City with her and start his life anew; he said yes to that, too. I ask him if there’s some part of him that regrets giving up science and taking a chance on this wild new existence. He pauses. “A very small part,” he says. “I wasn’t 100 percent sure it was the right decision, but I didn’t want to go to MIT. I knew in my heart that I didn’t want to do that for the rest of my life.”

In place of that path, a new one appeared, littered with glitter and intoxicants. All of a sudden, thanks to Jones, Lundgren was hanging out with the likes of Andy Warhol, David Bowie, and Michael Jackson. Jones brought him on set while she was shooting the James Bond picture A View to a Kill, and at her suggestion, he tried out for a bit part and was cast as a KGB tough named Venz. He took acting classes and learned that Stallone, then one of the most famous men in the world, was looking for someone to play his rival in the next Rocky flick. Out of a reported casting pool of thousands, Lundgren got the part and stepped into the ring as the character that would become his bête noire.

In Rocky IV, we don’t hear much from Lundgren. Most of the time, when we see Drago, he’s being talked up by his wife Ludmila (Brigitte Nielsen) or his trainer Nicolai (Michael Pataki). Drago, himself, simply towers and glowers. On the rare occasions when he does speak, the audience perks up and remembers his words. When he savagely beats Rocky’s pal Apollo Creed in an exhibition match, giving him mortal injuries, Drago flatly tells journalists, “If he dies, he dies.” When he’s about to fight Rocky in the climactic match in Russia, he stares our hero down and calmly intones, “I must break you.” Of course, the good old American can-do spirit takes Drago down in the end, and when we last see him, it appears that the Soviet politburo is deeply unhappy with his loss.

Late–Cold War audiences in the U.S. were quite happy to develop a lovingly hateful relationship with the character, and Lundgren was abruptly thrust into the spotlight. Lead roles in Masters of the Universe (that’s the He-Man movie), The Punisher, and Universal Soldier followed. Then, in the ’90s, the wheels fell off. He found himself stuck in the same sort of parts over and over again, playing dead-eyed killers in movies of decreasing quality, and eventually getting stuck in a direct-to-video purgatory. What’s more, he was partying too hard and gradually ruining his marriage to fellow Swede Anette Qviberg. “I made a lot of mistakes and I had a lot of traumas from my childhood that I let run me and run my life,” he says. “It’s called escape behavior. I was doing crazy physicalities and fighting and stunts and drinking alcohol and having affairs. You’re trying to escape that trauma, but you can’t.” As the 2010s dawned, Lundgren was a classic case of “where are they now?”

Two things happened. First, Stallone called him up and got him to join the cast of The Expendables, putting him back on the blockbuster map. Second, a post-marriage girlfriend encouraged him to start meditation and therapy — he was resistant, but after the relationship fell apart, he gave it a try. The dual practices allowed him to deal with the legacy of his father’s abuse for the first time, and the results were profound. Ever the performer, he achieved an apotheosis by delivering a TEDx talk in 2015. “The way out is through,” Lundgren says. “I had to speak about it publicly.” The transformation had a tremendous impact on his professional prospects and has brought him to a place where he could feel comfortable taking meaty roles again. “I couldn’t have done this ten years ago,” he says. “I had too many hang-ups, too much crazy energy.” Now, he was ready.

Nevertheless, Lundgren was still deeply nervous about returning to Drago’s boots. “I was scared of going back and either messing it up and destroying that legacy or having to play another stereotypical, one-dimensional Russian bad guy,” he says. “But when I met the director, Steven Caple, I realized in two seconds he was a real artist, real director, who is interested in the drama of trying to bring back my character.” He signed on and got to work on getting into Drago’s headspace for the first time in more than three decades. “I tried to find parallels in my own life,” he says, and that’s where the bit about being misunderstood as a thug comes in. Just as he had chafed at being underestimated, so too would his Drago. “I know all of those things,” he says. “I would use that.”

This time around, we meet Drago in impoverished exile in Ukraine, having long ago lost his marriage, his career, and the respect of his fellow Russians. All he has left is a son, Viktor (Florian Munteanu — true to franchise form, he’s not Russian), whom he’s been training as a boxer. A gimlet-eyed American promoter notices Viktor and recruits him to challenge the late Apollo’s son Adonis (Michael B. Jordan) for the heavyweight championship. Given that Adonis is being trained by Rocky, Drago can’t help but crave revenge through his son.

“Drago’s like those pageant moms dressing their daughters up and pushing them so hard to be perfect girls,” Caple tells me. “This was a darker version: He’s training this pit bull who has to go above and beyond to please dad.” Munteanu and Lundgren swiftly developed a significantly healthier version of that May-December relationship, with gentle advice about how to navigate Hollywood and intense physical training sessions. Munteanu remembers Lundgren’s workouts as almost frighteningly impressive for a sexagenarian: “Dolph’s used to using the old methods, which are like, Go hard on your body,” he says. “No pain, no gain.”

Perfecting his body is old hat for Lundgren. Perfecting his tongue, though, was another story. Though Drago spends much of the film being his old silent self, he talks significantly more often this time around, and it’s often in Russian, a language Lundgren doesn’t know, despite playing more than his fair share of Slavic-accented tough guys over the years. Thus came intensive Russian-language coaching for him and Munteanu. “That was so tough,” Lundgren recalls. “I had to learn 40 lines in Russian, and I had these cards, cheat cards, with all the Russian lines phonetically, and you still don’t really know the nuances of the language. As soon as I’d do a take, I’d go over and look at [the language coach], she’s behind the monitor, and then she’d still tell Steven, ‘No, it wasn’t right.’”

But perhaps the biggest challenge came in dealing with his old sparring partner, Sylvester Stallone. “He’s never really accepted me, I think, as an equal,” Lundgren says. “I’ve always been a kid to him, y’know? It’s almost like a father figure. There are some unresolved issues.” (Stallone declined to be interviewed for this article.) Those issues came to the fore while shooting a scene where Drago and Rocky trade terse words in a restaurant. “The scene’s been changed,” Lundgren says. “The original scene, everybody would’ve loved that scene. But Stallone, he started rewriting that scene a little bit and I didn’t like his changes. The director didn’t want to confront him much because he’s a 30-year-old guy and Stallone is Stallone. So I had to confront him.”

Lundgren laid out why he thought the changes didn’t fit how Drago would talk, and Stallone pushed back. “There were a few lines in there that Sly had written that made Dolph feel like it was going back to Rocky IV vibes,” Caple says. Lundgren remembers a drawn-out tussle of words: “[Stallone] had to sit there for one hour and we were negotiating how to do the scene and were arguing about it,” Lundgren says. “And I realized that he realized, Whoa, Dolph’s grown up. Finally, he says something typical of Sly, like, ‘Hey, Can we do this fucking scene? Can we stop talking about it?’”

A compromise version of the scene ended up in the finished product, and it’s one of the most gripping moments in the film. Lundgren thinks that comes from the real-life tension in the room. “I have a lot of feelings about Stallone and maybe him having treated me a certain way in the past that I could use for that scene,” he says. “I could see he was a bit like, Oh, shut your hole. Twenty takes of animosity.”

All of that said, Lundgren claims he and Stallone have an equilibrium and an understanding. “We’re always good,” he says. “He’s been hard on me sometimes because, I think, people you love, you can be hard on them. But we’re good. Our daughters are friends. He’s charismatic and he’s just very, very special, and he’s special in my life.”

By this point, you’re probably getting a sense that Lundgren, even if he’s not a Method actor, is certainly attempting to put genuine resentments, regrets, and aspirations into his latest performances. That’s the case even in December’s Day-Glo CGI superhero fête Aquaman, where he plays Nereus, an undersea king and father of Amber Heard’s Mera. “That’s a father-daughter relationship, and I have a daughter that I love a lot,” Lundgren says. “I’ve had a lot of strain because of my drinking too much when I got divorced and all that. I wasn’t a really good father for her for a while. So I had some issues there that I could use.”

It remains to be seen how the world will receive Lundgren’s return to the fore, and he’s far from sure that it’ll all work out. That said, he says he’d love to do a dramatic role on television, if given the chance. (True Detective season four, mayhap?) He had a tiny role as a Russian soldier in the Coen brothers’ Hail, Caesar! that was cut from the theatrical release, and he wonders if he might get to work with them in a more substantial way in the future. “They were a little bit impressed by me, I think,” he says. “One of the Coens told me at the premiere, ‘Well, you know, there’s still a chance for you in one of our movies. Because we grew up in Minnesota, all our movies have Polacks, Jews, and Swedes. There’s always a crazy Swede in our movies.’”

That role could emerge, but in his private life, Lundgren is done being a crazy Swede, and it shows in Creed II. He’s the most compelling part of the movie, a quiet storm of regret and dedication. What really takes the character over the top, however, is the torrent of emotion Lundgren puts into Drago’s relationship with Viktor. I won’t spoil anything, but it goes in unexpected directions and ends up conjuring a vision of Rocky’s old foe that is radically different from the one we’ve seen before, yet somehow completely in keeping with the archetype we were introduced to in 1985. “Now, if I can feel I’ve proven something to myself, I won’t have that painful anxiety about it that Ivan Drago has about his life,” Lundgren says. “It’s weird that that fricking guy has become my alter ego in a strange way.” That may be, but by playing Drago so well in the new picture, Lundgren proves he is ready to escape the curse of Drago once and for all.

Nevertheless, the Rockyverse will still follow him to one extent or another for the rest of his years on this planet. As we chat, at one point the restaurant’s stereo starts playing Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger,” the infamous earworm popularized by its presence in the Rocky franchise. “Oh, shit, they put on the music,” Lundgren says, placing his head in his hands. “Oh, shit. It’s, like, following me.” We both laugh. “Do they know you’re here?” I ask him. “I don’t know,” he replies. “Maybe it’s just meant to be.”