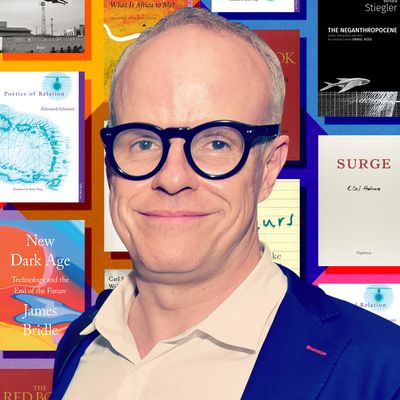

Bookseller One Grand Books has asked celebrities to name the ten titles they’d take to a desert island, and they’ve shared the results with Vulture. Below is art curator and artistic director of London’s Serpentine Galleries Hans-Ulrich Obrist’s list.

At the age of 18, I made a pilgrimage to Vienna to meet the artist Maria Lassnig. I was fascinated by her amazing “body awareness” paintings. It was during this first meeting that she told me about the great Friederike Mayröcker, one of her favorite poets. Ever since, I have read every book Mayröcker has written, and my favorite is her recent Trilogy, and particularly the book Fleurs with all its amazing neologisms. To her, poems are like watercolors, while prose is like a stone sculpture. She now creates collages of the two, which she terms ‘proems.’

The latest book by the great poet and artist Etel Adnan is a fragmentary exploration of reality. “Mountains are languages and languages are mountains.” These are aphorisms for the future. During my most recent visit, she added to my Instagram archive of handwritten notes the words, “Your identity is your prison.”

Mabanckou is one of the greatest storytellers, famous for his book Black Moses. Les Cigognes Sont Immortelles, which combines the personal and political, shows the impact that history, violence, and civil war has on a family, against the backdrop of colonization and decolonization. I was particularly struck by this recent quote of his: “The civilization of tomorrow is the sum of marginalities.”

Stiegler recently collaborated with me on the Serpentine Gallery’s daylong Work Marathon public event, gathering experts from around the world to consider economics for an age of planetary-scale environmental crisis. With The Neganthropocene, Stiegler looks to reverse the phenomenon of entropy that faces us, giving us new agency.

James Bridle’s Cloud Index was one of the first Serpentine Digital Commissions shown in 2016 where he explored the relationship between the climate, data, and what he called “computational thinking.” In his groundbreaking 2018 book New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future, Bridle suggests that the age of Big Data will not bring a better understanding of the world but a reduced perspective dominated by the limits of technology. It is a shuddering, urgent, brilliant warning about our current direction of travel.

I have read every word that Robert Walser has written. After a nervous breakdown in 1929, Walser spent the remaining 27 years of his life in mental asylums, going from outer exile to inner exile. Walking replaced writing for Walser, and from 1936 onward his friend Carl Seelig recorded their conversations while they walked in Switzerland. It’s an extraordinary book that prompted me to found my first museum in 1992: a migratory Robert Walser museum on the theme of the periphery.

This legendary writer from Guadeloupe who now lives near Arles is famous for books such as Crossing the Mangrove and Segu. This book is about her formative years at a time when African colonies became independent in the 1950s and ’60s. Personal and political, it includes her time in Ghana when Kwame Nkrumah was president, and her encounters with Malcolm X, Che Guevara, and Maya Angelou. It is also the story of a young mother raising four children and of finding the freedom to be a writer.

Cabrera was a Cuban writer and activist who died in 1991. Her masterpiece, El Monte, is yet to be translated into English. It is a pioneering anthropological study of the African-Cuban traditions. She was the ultimate pilgrim, a witness and historian resistant to official histories, someone who was, as the great historian Eric Hobsbawm wrote, in relentless “protest against forgetting.”

Glissant is a writer I read every day for 15 minutes. His poetry, novels, and philosophy have such urgency today. Here, he focuses on the Caribbean archipelago, an island group with no center, just a string of different islands and cultures that shapes his concept of “archipelagic thought,” elevating diversity as an antithesis to continental space, which makes a claim to absoluteness and tries to force its world view on other countries.

This book was given to me by friend and colleague Ben Vickers, and although it was considered by Jung to be his most important work, very few people had seen it before it was reproduced as a facsimile edition in 2009. During the First World War, Carl Jung embarked on an extended self-exploration, which he referred to as his “confrontation with the unconscious,” culminating in this extraordinary illuminated volume created between 1914 and 1930. Best described as an early example of biohacking the mind, he developed profound journeying techniques that took him to the essence of his inner cognitive processes, which he called active imagination. The Red Book charts these visionary moments in Jung’s life with great illumination in a mode akin to the medieval manuscripts of the saints and William Blake’s The Marriage of Heaven and Hell. Its true significance has yet to be understood in the 21st century.