Adapted from the dramatic podcast by Micah Bloomberg and Eli Horowitz, Homecoming is Mr. Robot creator Sam Esmail’s ultimate film-history playground. Co-produced by Amazon and Universal Cable Productions, it’s a military thriller with a mystery at its heart, a narrative that unfolds across multiple timelines, and a fascination with the persistence and malleability of memory.

I’ve recently gone from being a viewer of Esmail’s work to a friend and collaborator, which is why I don’t review Mr. Robot anymore. Last summer, Esmail reached out to me about doing a nonfiction series about the history of cinematic style, and I’m developing that project with Esmail and my regular filmmaking partner Steven Santos. Many of our phone conversations about the series detour into discussions of 1970s movies, paranoid thrillers in particular — a shared area of interest that informed Esmail’s direction of Homecoming.

Last month, we spoke at length about as many aspects of Homecoming as we could fit into an hour and recorded it. The following transcript of our conversation goes into detail about the show’s visual style, its use of music, set design, composition, and moviemaking technology, its lead performances, and its character-building touches, as well as Homecoming’s relationship to Esmail’s favorite thrillers and how it feels to direct somebody else’s material after making a series that he created and helped write.

We’ve also used an audio recording of our talk to create a video essay, concentrating on aesthetic and technical aspects of the show. Much like Homecoming, which isn’t shy about acknowledging its inspirations, you can think of the video as its own throwback, to the era of DVD commentary tracks.

Spoilers abound, so you probably shouldn’t dive into this unless you’ve watched the entire show.

Why this particular project, and what drew you to it originally?

When I first heard the podcast, what struck me the most was that it was the kind of thriller that I don’t often see today. Most thrillers that are made today are basically action films with some twists and turns, and dramatic scenes in between.

This was less an excuse to make a dramatic action film than a thriller like the ones I grew up watching — like, obviously, the classic paranoid thrillers of the ’70s, and even the great thrillers of the late ’90s, and you can even go back to Hitchcock. These are more thrillers based on characters and relationships, and the secrets that they keep from one another. That was something about [the podcast] that took me by surprise because I had not seen it before. It had this throwback feel to those character-based thrillers that really inspired me to become a filmmaker in the first place. And the other great thing about Homecoming is that it wasn’t trying to do that; it just was that. It still had this modern-day relevance to it, and I loved that it was inadvertently a throwback thriller.

The podcast is very much in the tradition of those old radio dramas that used to be common before TV came in, and the writers, Micah Bloomberg and Eli Horowitz, obviously had to think about how to make audio that felt cinematic — like what used to be called “theater of the mind.” But that’s a different kind of storytelling than what you’re doing here, which has to be strongly visual first. How do you translate one medium to another?

I’ve got to say, when my agent told me about it, my first response was that I wasn’t interested in adapting something into a movie or TV show because it’s popular. That doesn’t make any sense to me. If it was great in one medium, why is everyone’s knee-jerk reaction, You’ve got to turn it into a movie or TV show? But I wanted to listen to the podcast anyway, purely because I’d heard good things about it. And when I binged it the first time, it was purely as a fan.

I was so taken by it that I binged it again with my wife in one sitting. And then I decided, Oh, I’m going to binge it one more time to see if there is something that could translate. Is there something that could be expanded upon that was limited by the fact that it was in that audio format? In the third binge, I got to the scene where Walter and Shrier have this theory that they’re not actually in Florida, so he steals the van, Walter comes with him, and they happen upon this eerie town that looks plastic, and it turns out it’s a Florida retirement community, so Shrier’s theory turns out to be false. But that story gets told by Walter to Heidi, and he’s chuckling because he already knows the ending.

That was when I realized, Here’s an opportunity to actually be with those characters, to feel the tension and suspense with them, to actually question whether or not Shrier is right about his theory. It was something they couldn’t do in the audio format because it’s all based on these conversations, so you had to tell the story in hindsight. And that’s where I thought we could turn this into something different, something visual. I did not want to just remake the podcast. I wanted it to be this stand-alone story that is its own creature. You could listen to the podcast, enjoy the TV show, and they’d be two separate experiences.

I want to ask some questions about the filmmaking. Throughout Homecoming, you do a lot of long takes with few or no cuts. What do you gain from shooting a scene in that way, as opposed to the standard way where it’s laid out in fairly simple shots cut together?

I’m going to give you a weirdly pretentious answer — I hope it doesn’t come off as too pretentious! — but I often dream in long takes. Dreams don’t have cuts for me. And when I think about a scene and I think about the mood, I want to go as long as possible because I feel like a cut breaks the thought. I feel like a cut breaks the tone. I’m not a fan of these very cutty, handheld-y kind of films or TV shows, where a cut is just every half second or every two seconds, where you’re desensitized to it. To me, a cut should say something and be impactful.

When it is this sort of long take, it brings me into more of a dream state. And honestly, the great films that I grew up loving are the ones that do that to me, where I leave the theater thinking I’ve just watched a memory or a dream or something that has just flowed into my subconscious. Obviously, not every scene needs to feel that way, but a lot of scenes to me are about pushing that tone and that atmosphere as much as possible.

That’s also one of the reasons why we do the ending credits the way we do. We play out whatever happens in the last scene of an episode, and then after that, there’s this real-time snapshot that’s continuing on as the credits go. There’s a lingering effect. That’s what I felt when I listened to the podcast. It’s not this “wow” ending or this cliffhanger, necessarily, it’s really just about this subliminal feeling that’s starting to bubble up to the surface. There’s something more menacing about that.

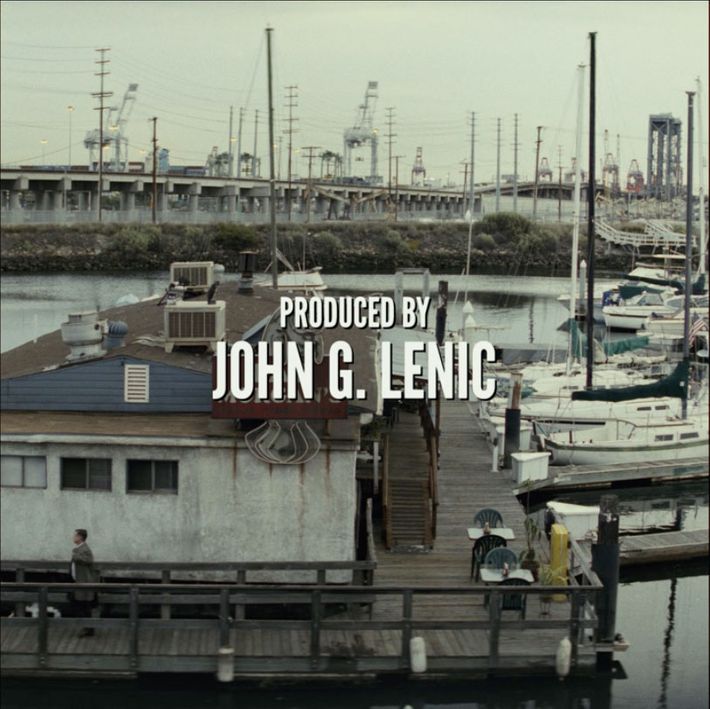

Every episode ends with, I guess you’d say, a meditative moment. The action proper has concluded, but you’re letting people continue to exist in the space. In some cases, it’s after the important characters have left. In the scene that ends the first episode, Carrasco picks up his briefcase, walks off down the dock, and you cut to a wide shot of the dock, and you’re just staring at it.

It’s dreamlike to me. It’s subliminal. There’s something about it that feels unsettling, but not overtly so, and it stays with you. And look, part of me is also playing with the form of this binge-modeling because I knew it would all be dropped on Amazon in one day. Everyone’s inclination is to hit next as soon as the credits start rolling. I didn’t want that for this show. I wanted that feeling that this is going to wash over you, that something’s bubbling and it’s growing, and that’s part of the reason why we did that.

I wondered if there was a tactical reason for doing that. Like, “We’re not going to be in a rush here. We’re going to sit here and think about what we’ve seen, and I’m going to make you do that.”

I’m not trying to disrupt the binge model or anything like that. I just felt it worked for this story because of the way the story is constructed. Again, it’s not these wham-bam cliffhanger moments; it’s this very slow-burn bubbling to the surface — you know the menace is right around the corner.

We’re also dealing with memory, and going back to the question about long takes, it’s the same thing with the lingering endings. That was the reason we wanted to embrace this dreamlike, meditative state. We felt like that matched what was going on with Heidi and what was going on with the men in the facility.

I also wanted to ask you about the scenes where Carrasco is basically being a detective. You have scenes where he’s in this Kafkaesque documents warehouse, like something out of Raiders of the Lost Ark or Citizen Kane, or the offices in The Hudsucker Proxy and Brazil, or one of those cavernous interiors from Orson Welles’s film version of The Trial. What’s your thinking there?

When I think about any sequence or scene, I want to think about it in terms of how it enhances that character’s POV. This is Carrasco’s world. If you put him in a regular office basement with files, it wouldn’t seem as challenging to him. He’d devour those papers within minutes to find the information very quickly. I wanted it to feel like this monolithic thing that Carrasco would be challenged by, even if it strained credulity. I never minded that because it felt real through Carrasco’s point of view. That’s what this task feels like to him, this big undertaking where he’s going to have to climb Mount Everest to find the information he’s looking for.

And, yes, it’s Kafkaesque. Raiders and The Trial are good references. Carrasco is in a job where he feels like it’s going nowhere. It’s pushing papers. It’s this primitive, surreal nightmare to him, and he’s trying to wake up from it. To me, the beauty of Carrasco is placing him in the most nightmarish environment possible, and seeing that he doesn’t blink! He persists.

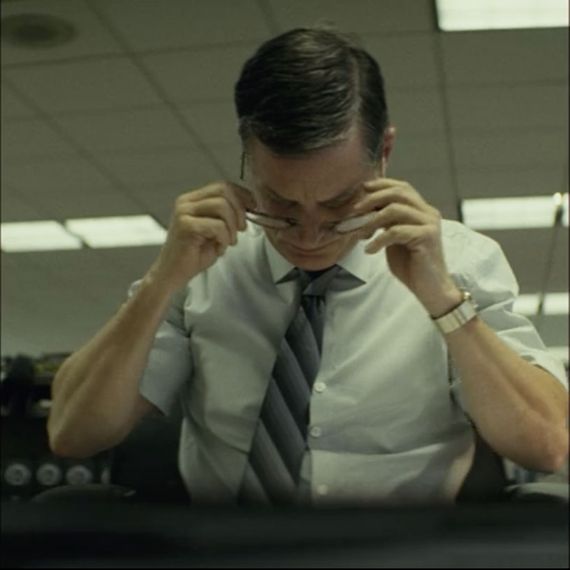

You’ve got this one moment in the second episode, starting on a wide shot of the office. There’s a 30-second slow zoom on Carrasco as he calls Walter Cruz’s mother, Gloria, on the phone. Tell me about that shot.

To get that effect, we had to boost up his chair. Ordinarily, you wouldn’t be able to see their faces. On set, the camera operator said that was going to look funny, but it was worth the payoff. Yes, it’s a little surreal. But the idea is that he is this cog in this monstrous, bureaucratic, red-tape nightmare. The shot doesn’t work if you can’t see that his eyes are just slightly above water there.

I always suspend logic for emotion. If it feels real, or it feels like what I’m going for, we should abandon reality a little bit and go for that. I’m not a documentarian. We’re not trying to shoot things for naturalism. We’re trying to shoot things for a feeling, for a vibe, and that was Carrasco’s world. He’s in a sea of red tape, and he’s just barely floating above the water line.

Speaking of a cog in the machine, I wanted to ask you about the visual analogies between Carrasco and Heidi. Not only are they both, from a narrative standpoint, cogs who decide to be something more than that and suffer the consequences, but you often juxtapose them in a way that makes us see that. You’ll go from a scene of Carrasco moving through his environment with the camera following in front of him, and then you’ll follow Heidi in the exact same way. Sometimes you cut between them in different locations or time periods, and they’re in the exact same spot in the frame.

Absolutely. The show starts with him investigating her, and you think it’s an adversarial relationship, but I wanted to set up from the beginning that they were after the same thing, and eventually have you realize it.

You start the series off in the very first episode with a long take of Heidi, and then there’s that brief shot of the pelican coming to rest, and then the very next shot is another long take establishing Carrasco. Right away, subliminally, the audience is thinking that these two characters are similar, even though they’re not on the same side just yet.

Exactly. That was something I wanted to foreshadow because I didn’t want to mislead the audience into thinking Carrasco could be our Big Bad. I also didn’t want you to think Heidi was the Big Bad either, but Carrasco’s pretty genuine from the get-go, and Heidi’s a little more aggressive with him in the first episode. I really wanted to lay down the foundation that these two are actually looking for the same thing. It was a way to draw parallels without being overt about it, because obviously there is that suspense of What’s going to happen? Will Carrasco win out? What’s he going to find that Heidi doesn’t want him to find?

But hopefully, if we did our jobs right, you’re not thinking that this is going to be the showdown. The way we filmed [Bobby Cannavale’s character] Colin, that’s where you find, Oh, okay, that’s where the true adversary is going to be.

I’m curious about two bits of business Shea Whigham does as Carrasco: the clicking of the pen and those glasses that break apart at the bridge. Where do those come from? How do they fit into the mix here?

Shea’s so diligent and such a hard worker. He could be doing something as simple as clicking a mouse, looking at the computer screen, or taking out a business card, and we just keep doing it and refining it. I’ve never seen a guy so committed to expressing something genuine at every moment. Early on, we had a good conversation about who this guy was and what the particulars were, and we didn’t want to make a cartoon character. We wanted to be very intentional about every little choice that we make.

The breakaway glasses were simple: Carrasco was all about the work, and the glasses needed to be as easy and accessible as possible when he needed to read and when he wanted to take them off. It was about saving that fraction of a second it would’ve taken him to move those glasses onto his face, as opposed to the breakaways that could’ve been just a little bit faster. It’s the same thing with the pen clicks. We wanted to be as specific with the gestures as possible.

As you did on Mr. Robot, you often directly quote the movies that you’re inspired by. You do it here from the very beginning, when you have a piece of music from, I believe, Dressed to Kill in that opening sequence.

Yeah, that’s basically the opening cue to Dressed to Kill.

Why did you decide to do that? I know certain directors, like Martin Scorsese and Quentin Tarantino, do it. But there’s some argument about whether or not it’s too much like you’re telling people exactly what movies you were inspired by. Where do you stand on that issue?

Well, here’s what happened. As I was talking to my creative team about the tone, what I typically do is reference a lot of films. A lot of the films were Brian De Palma, Alan J. Pakula, Martin Scorsese, Alfred Hitchcock, Stanley Kubrick, the list goes on and on. And then when it came time to talk about music, I bristled at the idea of asking a composer to ape that music or that tone. There was something about it that just felt wrong to me. It felt like the best version of that would just feel incredibly derivative. I didn’t want it to feel like this half-measure of trying to sound like a soundalike. So I said, “Why not use the real thing?”

You’re using all the latest technology to shoot your TV shows, and yet the way that you talk about directing is like an old-movie approach. You seem to be thinking, How can I use lighting? How can I use composition to express an idea? One example I use when I talk about this with students is the scene in Raiders where Indiana Jones walks into the bar in Nepal. You hear the door open, but you don’t see him, and he’s announced by this enormous shadow on the wall, which gets across this idea that he’s a ghost from her past, and also that he’s larger than life. It’s like you’re dealing in metaphors here, almost.

That’s what it is, isn’t it? Isn’t that what a film is? Isn’t it a metaphor filled with symbolism? That’s the best use of the visual medium — that we’re creating a story with images and not necessarily with anything else. The images tell the story on their own. Obviously, there are many other components to it, but that’s the birth of it, right? It was done before there was even sound — you did it in silent film where it was about these images edited together in such a way that it told you this story. When we talked about doing the show, we talked about how every image and every cut needs to say something.

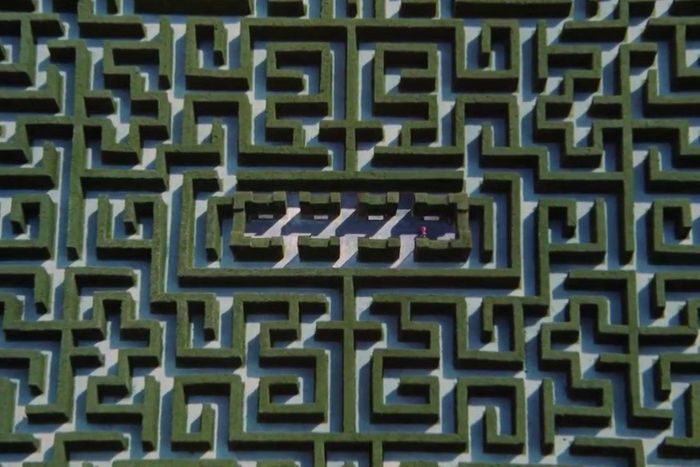

The scenes where the camera seems to rise to a Godlike height overhead is a Hitchcock or Scorsese or De Palma thing to do. I’m wondering when we see people in the Homecoming facility, or Carrasco in his office, are we always looking at a set? When we’re in the lobby of the Homecoming building, is that a set? Are some things sets and others are real locations? Break that down for me.

It’s a mix. If I had my druthers, I’d build everything on set because I could control it and put the camera wherever I want, but no. Obviously, the facility is a set. It’s a two-story set that my production designer, Anastasia White, who did an amazing job on Mr. Robot, built. All two stories, every room. It’s not like a set where you walk around a corner and there’s nothing there, or you open a door and that’s the end of it. Because of the nature of the long tracking shots, Anastasia had to build the detail into everything that we could see, which is essentially the entire set.

Then we mixed that in with real-life locations. The lobby had to be real because Heidi would have to go in and out of the world through there. For Carrasco’s office, we got lucky and found a great location with high enough ceilings so that I could move the camera around as much as I wanted to. That was a real place, but we treated it basically like a set.

And, yeah, those overhead shots were really important to me. That’s something I brought up to my cinematographer, Tod Campbell, right away. I wanted it to feel like we, or somebody, were a third-party observer in all of this. I think that’s part of the reason why the great masters do those shots. They want the story to have that voyeuristic feel, and I thought it was really important to do that for this show.

In the drone shots — I guess they’re drone shots? — where you’re following a vehicle, there’s something about the camera movement that feels very weird to me. It looks like the camera is physically attached to the back of the car because it’s very rigid, like it’s following the car exactly, but that can’t be right, can it? I just don’t know how you did that shot. What is that?

It is attached to the car. It was underlining, once again, this observational third eye that I wanted to suggest to the audience. I wanted the same effect in all the driving shots. We stuck an arm onto the back of the car, and it kind of jutted out, so it’s locked to the car. The car moves left; it moves left. It’s almost like a body cam for the car. Then the effects guys would come in and paint out the arms, so you wouldn’t see it in the shot, and it feels seamless, like you’re moving with the car.

There are a lot of shots where you’re looking at people through windows or in their homes, creeping in on them very slowly. And I’m asking myself as a viewer, Who is looking at these people? Is there anyone looking at them? One of my favorite examples is in the sixth episode, where you have a long shot through the Chinese-restaurant window of Heidi and Colin. I got a sick feeling in the pit of my stomach seeing it. It made me wonder if Colin’s guys were watching them.

What are you thinking when you do that kind of thing? What are you trying to make us feel when you shoot moments that way? Where does that way of photographing the story come from?

When you ask if it’s meant to represent the audience or some third party, my answer would be that it’s both. During this almost voyeuristic mental state that I want the audience to be in, I also want them to have this paranoid feeling that they’re being watched and listened to, that this [action] is being eavesdropped on, and it’s nefarious.

That particular scene you’re talking about in episode six, I didn’t want this to be just a normal date between two people. I wanted it to feel as if something sick was about to go on. I never wanted the audience to feel settled here, but I also didn’t want to just throw them out of whack completely. I wanted it to really be very deep in that subliminal, meditative state.

I felt like always positioning the camera in such a way gave you that incremental feeling of Am I supposed to be watching this? And then you jump to the next question: If I’m not supposed to be watching this, then why not — and who is watching this?

On Mr. Robot, starting in season two, you directed every episode yourself, and you were also writing many of them. Here, you’re only directing. How does it feel to just be directing?

It feels awful. [Laughs.] I’ll say this: Eli and Micah were a dream to work with. It has nothing to do with them. They are amazing writers, and I’d even venture to say that they’re way better writers than I am. I’m so glad the scripts turned out beautifully. But as a filmmaker, I have this streak in me that is quite controlling, and I really want to filter every aspect of the show through a singular vision. And that’s not to say that didn’t happen on Homecoming, because there’s an incredible collaboration between the writers as well as all my talented creative heads. But because I had so much respect for Eli and Micah, it was hard not to be able to manipulate the story as I saw fit as I went along.

I know that some directors don’t care. They’ll change or cut lines on set, change the location, do whatever it is to fit what they want to do. But I’m not like that. I had too much respect for Eli and Micah to steamroll them. So there were a lot of moments where I had to pause and really deliberate with them about certain scenes if I wanted to adjust or change things, and when they made a good point from a storytelling POV and disagreed or pushed back, there’d be a conversation that ended with collaboration, or we’d go one way or the other.

That part of it was a painful thing for me. I was so used to being more nimble when it came to changing things on the spot, and I own that, as a flaw in myself. I think especially in the first season of Mr. Robot, the controlling aspect was there because there was this weird lack of trust. I didn’t have my team of people that I had worked with for years. Now, I completely trust my costume designer, Catherine Marie Thomas, who’s brilliant. I completely trust Stasia [White], my production designer, who’s beyond amazing, as well as Tod [Campbell]. But this was the first time I had to deal with that on the writing front, and I have to say, it was pretty hard. I guess that’s another thing I will have to evolve on. As I hopefully continue to evolve as a filmmaker, I want to learn to let go a little bit more.