In the late 1980s, when her writing was in peak bloom, Lucia Berlin made a list: “The Trouble With All the Houses I’ve Lived In.” Her 33 locations ranged from Alaska, where she was born, to Idaho, where her father worked as a mining engineer, to New Mexico, where she lived at various times with each of her three husbands. Characteristic of her style, the list repeats words and phrases for emphasis. “Evicted,” Berlin writes of her home in Berkeley, California. Of Oakland, too: “Evicted,” “evicted.”

In her fiction, Berlin’s repetitions feel weightless, incantatory. But in this document — included in her memoir Welcome Home, out this week — they have a different effect. Rather than her awe, we feel her exhaustion, the drudgery of her repetitive chores. We feel, also, how fed up she is with her state of existential homelessness. When, and where, will she finally feel at ease?

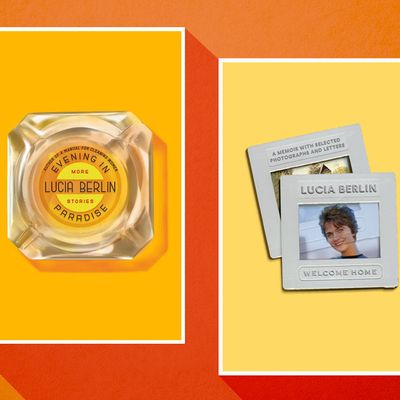

Berlin, who died in 2004 at the age of 68, was not a well-known writer in her lifetime. But in 2015, more than half of her short stories were published in A Manual for Cleaning Women, which became a best seller. The New York Times rated it one of the ten best books of the year, and Lydia Davis, who wrote the introduction, praised the stories’ “perfect coincidence of sound and sense.” This week, Manual’s publisher, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, releases not only Welcome Home — which Berlin was working on when she died — but also Evening in Paradise, a collection of 22 more stories that reaffirm her genius for transporting readers to all of the places she’s lived. Now that most of her work is between covers for a new generation, it’s tempting to assess her life alongside her fiction. Why does her writing resonate so strongly today — and not while she was alive?

In the introduction to Welcome Home, Berlin’s son Jeff writes that the vignettes in her memoir echo the stories she told him growing up — only now they’re “no longer masquerading as fiction.” Lines from Welcome Home are repeated verbatim in her short stories: frank accounts of major life events, details about makeup palettes and trained talking birds. Most writers borrow people and places from their lives, reshaping them into a system that feels meaningful to them. But Berlin seemed almost to transcribe her memories, over and over, into quick, lyrical scenes. Today, we might classify it as auto-fiction — the literary style of near autobiography whose practitioners include Sheila Heti and Karl Ove Knausgaard. As with Heti or Knausgaard, there’s a sense of urgency and compulsion in Berlin’s stories. In a letter she wrote to a poet friend in 1959, she laments that her writing is “bad,” but goes on to say, “I’m not an amateur […] if only because I have a lot of things I want to tell, to put down and say.”

The current popularity of auto-fiction, along with the impulse to recover women’s narratives, might explain Berlin’s resurgence. Of course, thinly veiled fiction is hardly new; the writers of the Beat Generation, whom Berlin considered her immediate predecessors, catalogued their emotional responses to their immediate surroundings. But in contrast to that largely male cohort, Berlin’s search — the desperation that compelled her to pour out her stories — was often more material than existential. The circumstances of her life forced her to grapple with questions like, Where will my sons and I live next year — or tomorrow? Will we be able to keep our hands and our feet warm? She did not, like Jack Kerouac, set her characters on a hero’s rootless journey — that perennial hallmark of (male) storytelling. Her women aren’t driven by their will, but by more basic imperatives: Do not have a drink this morning; do not get evicted. Survive. Berlin lived that way too, except that she also wrote. Her stories, so rich in palpable details, must have been a comfort, a way of returning home.

Because of her father’s work, Berlin spent much of her childhood moving from house to house. Then, during World War II, he was drafted, and Lucia, her mother, and her sister joined their extended family in El Paso. Uprooted, she wrote about missing her father and her childhood best friend, Kent Shreve (who features prominently in her fiction, his name unaltered).

It was around this time that she started writing letters. At 11, she wrote to her father, and already her voice was both playful and direct. Of a trip to the theater, she wrote, “I couldn’t go and besides I didn’t want to.” Her father replied consolingly: “Though we may live on a mountain peak one year and in a black canyon the next, […] our beautiful house will be built in our hearts.” Berlin didn’t inherit her father’s sentimental style; her words are tactile, specific. But his thoughts on home might have influenced her characters, who often make the most of uncomfortable places — in the cold or among rodents.

Her letters mention many such provisional living spaces. As a kid, she slept on Murphy beds, and on the train ride to El Paso, her sister was carried in a dresser drawer filled with blankets. But it wasn’t just her life as a transient that made her long for the solidity of a home. It was her tumultuous family, too. Her mother and her grandfather both drank heavily, and Berlin wrote that holidays in El Paso were like an “awful violent Faulkner scene.” Some of these misadventures were adapted into violent stories, like “Dr. H.A. Moynihan,” in which a young girl yanks out all of her grandfather’s teeth so that he can replace them with his self-made replicas.

Her family was her family, though, and she soon realized how much she depended on them for support. At 17, she fell in love with an older student, a Mexican-American veteran, and her parents eventually disowned her. Her mother’s disapproval featured in letters for years to come — and in many stories, including “Homing,” in which an older woman follows a daisy chain of “what if” scenarios beginning with the outcome of a thwarted young romance. The next few decades of Berlin’s life would be full of incident, but always with an undertow of need, both material and spiritual.

A few months after the blowup, Berlin married a sculptor named Paul Suttman. She didn’t feel tenderness toward him, but awe, and a willingness to defer to his supposed artistic genius. “I held the hot part of the cup and gave him the handle,” she writes in her memoir. “I ironed his jockey shorts so they would be warm.” She writes, also, of his many requests — that she wear dark eyeliner, but no lipstick; that she sleep on her stomach to “correct” her upturned nose. Year later, Berlin would turn this portrait of a controlling husband into the story “Lead Street, Albuquerque,” in which a woman reflects with pity on an old friend subject to her partner’s whims. “You get the feeling no one had ever told her or shown her about growing up,” she writes through the voice of a bewildered narrator, “about being a part of a family.” It was as if Berlin no longer saw in herself the person she used to be.

Berlin bore their first son to help Suttman avoid the Korean War draft; when she became pregnant again, he left. The day before her second son was born, she met Race Newton, who was playing that night at a jazz club, and they were married soon after. With Race, Berlin began writing more seriously. She still deferred to him and his work, but her second marriage did offer her something new. When she visited Race’s family in Little Falls, New York, Berlin wrote to her friends out West, awestruck: “Everything is so cyclical and ORDERED and NICE.” It was order that she coveted, and, at the time, she believed family life would provide it. “I’ve never known a family,” she wrote, calling the possibility both “nice” and “terrifying.” Regardless, she concluded, “I suddenly have 100s of things to write.”

Around this time, Berlin mailed some of her stories to Kerouac. It’s not hard to imagine why she would’ve sought the famous writer’s advice; there are at least superficial similarities between the two. Both wrote about vagrancy, having lived in cars, trains, and buses. But while Kerouac’s writing sprawls, Berlin’s is more solid; it hammers. Verbs and nouns are granted whole sentences. Of her home in Idaho, she writes, simply, “Creaks.” Or, “scrapings and hisses and thuds.” Of Kentucky: “Fireflies. Fireflies. Fireflies.” There are no mixed metaphors about roman candles popping like spiders. There’s just the word itself, ringing or buzzing.

Kerouac, who felt his childhood was tarnished by order, tried to escape it. But Berlin, who grew up on the road, sought order in her life, and finally, when that didn’t go as she planned, in her writing. Most of her stories are short and efficient, and most of her characters are remarkably still. They look out of windows. They sit on the roof. They bicker over drinks. Tension mounts as they perform the same task day after day: visiting a laundromat, riding the bus to work, cleaning houses, caring for children. These characters, plucked from Berlin’s adult life, didn’t go on adventures. Instead, no matter where they traveled, the monotony that so often accompanied a woman’s life invariably followed. Still, there are moments of drama, of rupture, when something bright and lovely peeks through, as through a ceiling crack.

In the title story of her breakthrough collection, a cleaning woman is stealing sleeping pills for her growing stash. Her husband, Terry, died recently, and she’s maladjusted to the listlessness of her new life, the absurdity of some of her clients’ belongings (“Elevator shoes?”). The story goes on like this: She waits for her bus, she cleans, she steals a pill. She waits again. (“Poor people wait a lot,” she writes.) There is routine, but no forward movement, no meaning to glean from all this ennui — no order. It isn’t until she meets a first-time client, a vivacious woman who speaks solely in idioms, that the story takes a quick, page-long turn. The narrator is tasked with finding her client’s missing puzzle piece. When she does, she cries out, and the two women rejoice. Then, in a wrenching line, the narrator addresses her dead husband, guiltily: “Ter, I don’t want to die at all, actually.”

It’s a neat encapsulation of Berlin’s work, and of her life. There’s an ambivalence about domestic spaces, which are stifling but also a comfort. And, amid so much chaos, something as small as a found puzzle piece is cathartic. There’s delight, relief. For a moment, there’s order.