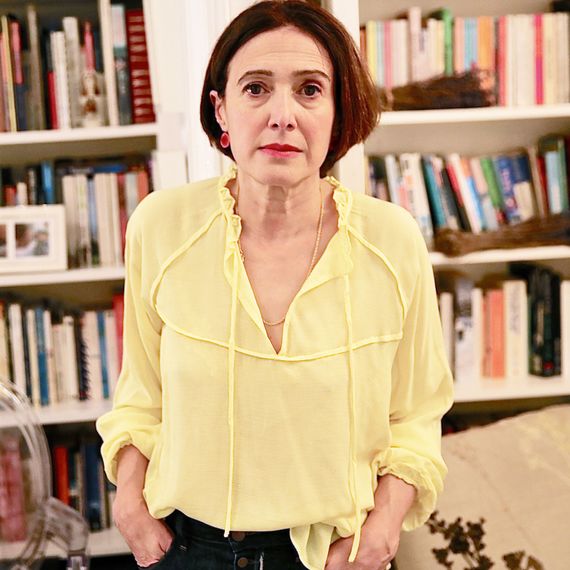

Marina Benjamin couldnÔÇÖt sleep. She tried therapy, pills, herbal tea, and every other home remedy well-meaning friends like to foist on insomniacs. Nothing worked. Eventually, she stopped fighting it, and decided instead to follow the path insomnia had opened up into her subconscious mind ÔÇö to use her condition as both a subject and a tool for her writing.

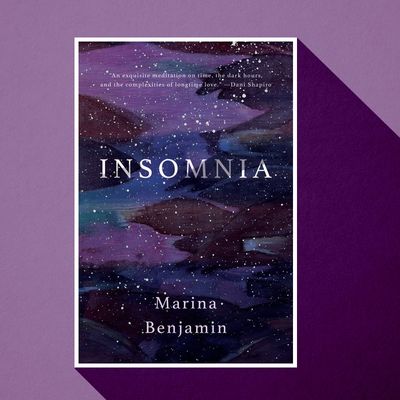

The result of that exploration is Insomnia (out November 13 from Catapult), a memoir in roving fragments that mirror the workings of a sleepless mind. The fractured narrative braids together anecdotes involving her soundly sleeping husband, reflections on insomnia in classic tales from the Odyssey to the Epic of Gilgamesh, representations of sleeping women in art and culture, interrogations of dreams and a thorough social history of medical sleep treatments. Periodically, we return to the pitch black of BenjaminÔÇÖs sleepless bedroom.

Benjamin spoke with Vulture about the cultural history of sleep, the ways we pathologize womenÔÇÖs anxiety, our submission to the ÔÇ£clock of capitalism,ÔÇØ and how the middle of the night is a great time to clear your inbox.

The book describes my personal journey with insomnia, moving from very fretful to very delusional and then to a kind of ecstatic state. That was very true to life because in the period I was writing, I was suffering very badly with insomnia. That led me to cognitive behavioral therapy [CBT]. It led me to pills. It led me to think thereÔÇÖs something wrong with me. I did not respond well to treating myself as a patient suffering from a malady. But if I thought of it more as something constitutional that I could accommodate, then I could get into a groove. I would start getting up and reading and writing, and that kind of worked.

This meant developing a sense of the night: its potentials, its terrors, its torments, but also its doorways ÔÇö all of the things that are different from waking consciousness during the day. The conscious and┬áunconscious minds are not separate; the mind is perpetually trafficking between these two states, and as a result of being┬áinsomniac IÔÇÖve learned how better to┬átap into my deep-seated concerns and commitments. I also feel closer to my dreams, as if my imagination has somehow become more porous, more open to all kinds of experience. These effects are especially useful for a writer, because they allow you to capture your own contrariness more effectively.┬áWhen youÔÇÖre awake at night I think thereÔÇÖs a sense in which a little bit of that unconscious bleeds into night waking. ItÔÇÖs about paying attention to that, listening in, working with it rather than fighting it.

You can really feel delusional at night. You sometimes get this sense of grandiosity, as if youÔÇÖre in touch with the universe and have these awesome mental powers. But thereÔÇÖs also this sense of connection because no one else is awake, so thereÔÇÖs nothing between you and the stars. YouÔÇÖre aware of your material self ÔÇö that youÔÇÖre a little speck of existence ÔÇö and thereÔÇÖs something quite comforting in that, which you can take with you into the daytime.

ThereÔÇÖs so much written already on the medicine of insomnia. I wanted to take a different approach, but nod gently and say, ÔÇ£Yeah, IÔÇÖve read it.ÔÇØ I was very interested in approaching sleep and night-waking as a literary subject. We donÔÇÖt write about sleep because weÔÇÖre unconscious, but I was really interested in writing about absence and lack and longing, all those negatives. ThereÔÇÖs a lot of poetry about insomnia but not much literature, not much prose.

I brought in references to Scheherazade, and to Penelope from the Odyssey. Penelope is one of these characters whoÔÇÖs principally known for being awake at night. Her wakefulness is intriguing because itÔÇÖs a literal vigil, waiting for this husband of hers. So I really loved that whole idea of ÔÇ£what did wakefulness mean?ÔÇØ Penelope also represents longing; the more something is not there, the more we want it. And of course we know that desire works like that. ItÔÇÖs perverse.

Insomnia is tilted particularly at asking about womenÔÇÖs states of mind, because I think womenÔÇÖs anxiety doesnÔÇÖt have many places to go in our culture, and so it pops up at night. And when it does manifest itself, itÔÇÖs often pathologized. In the 19th century for example, you had the rest cure, where women with nervous conditions were put to bed because their waking presence was just too threatening, or just too destabilizing, for men. A lot of the women who were experiencing these nervous conditions were the ones chafing at the limitations of the roles that society gave them. So here was the cure: Put them to bed.

That seems almost barbaric now, but then I just think to the 1990s when you had chronic fatigue syndrome, and exactly the same thing was happening. Professional women were being put to bed.

And currently, there are these so-called ÔÇ£sleep diets,ÔÇØ which IÔÇÖve experienced. It came as a real surprise to me ÔÇö and not just to me, but to all the other insomniacs who were in my CBT group. We were keeping sleep diaries and it was all a bit mysterious. We didnÔÇÖt know what they were for but we all dutifully kept them. You had to calculate how many minutes you were awake at night and every time you do them, your mind is ticking and awake. They only made it worse. We would then have to use these to work out the average amount of sleep we were getting a night. Then they said, ÔÇ£Right. Stick to that. ThatÔÇÖs as much sleep as youÔÇÖre allowed.ÔÇØ So thatÔÇÖs the sleep diet: You come in complaining that you canÔÇÖt sleep, they work out how much you average over a month, and then they say you canÔÇÖt get any more. The operating theory is to minimize the time spent in bed┬ánot sleeping, but the anxiety it creates is such that only someone for whom sleep is not a problem could conceivably┬ácontemplate it.

I am always intrigued by new innovations. In Tokyo, you have these sleep hotels that are like the morticianÔÇÖs slab ÔÇö you shoehorn yourself into a little box for an hour or two. Part of me thinks we might have a future in which all our states are controlled by drugs. WeÔÇÖll pop pills to be awake, to be asleep, to feel things, to not feel things. I donÔÇÖt know how the patterns will change, but I do know that the idea of sleeping eight hours a night is a post-capitalist invention. Pre-moderns had two sleeps, or they slept whenever they could, or they napped periodically during the day. But there wasnÔÇÖt this prescribed eight-hour stretch, which is very much about showing up at our desks at 9 oÔÇÖclock and clocking out at 6. Our body clocks donÔÇÖt always coincide with the clock of capitalism. And if you force them into patterns that donÔÇÖt feel right, weÔÇÖre all permanently kind of jet-lagged.

Writing this book changed my experience of insomnia. IÔÇÖm not as frightened of it and I donÔÇÖt fret as much. I lean into it more and get up and do things. I still sleep badly most nights, but I utilize more of the 24-hour cycle. When my wakefulness is┬áacute, I plough through novels, draft rough sketches for whatever┬áprojects IÔÇÖm working on. Sometimes, I clear the entire deck of my Gmail inbox, responding to every demand. I may not experience the refreshment of sleep, but I can get the refreshment of starting the new day with a clean slate.

But then, the more you lack sleep the more you want it. WeÔÇÖre all under-slept as a society, so we idealize it. ItÔÇÖs this golden burnished ideal that you canÔÇÖt obtain if youÔÇÖre an insomniac. So, you know, thereÔÇÖs nothing I like more than going to bed. I love it ÔÇÖcause IÔÇÖm so tired!

***

Disclosure: Lilly Dancyger is a contributing editor for CatapultÔÇÖs online magazine. Catapult press is the publisher of Insomnia, but the two divisions operate independently.