The fifth episode of The Romanoffs is about an artist who is accused of misconduct, without his knowledge and seemingly without basis. It’s the weakest thing Matthew Weiner has done since getting creative control over his own work. Telling the story of an openly gay piano teacher (Andrew Rannells) who’s investigated for unspecified behavior toward his young students, “Bright and High Circle” is a schematic and rather bloodless hour-plus — overall the weakest episode in a hit-and-miss first season of Weiner’s lavishly produced follow-up to his classic drama Mad Men. It subordinates characterizations to the apparent mission statement of director Weiner and the episode’s co-writer, Kriss Turner Towner: to caution viewers not to believe everything they hear, or spread rumors, or make snap judgments after an artist has been accused of sexual misconduct, as Weiner was last November during a wave of #MeToo allegations.

The extra-dramatic backstory: Kater Gordon, a onetime assistant of Weiner’s during the early years of Mad Men, eventually became staff writer and collaborated with him on the Emmy-winning script for season two’s “Meditations in an Emergency,” a memorable episode that juxtaposed the characters’ private and public dilemmas against the looming threat of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Last year, Gordon told The Information that after their joint Emmy win, Weiner said that she owed it to him to see her naked. Although it was an offhand remark, according to Gordon, it still shook her up because of the power differential between them, and her inability to figure out how to respond to it, or whether to respond. “I knew immediately when he crossed the boundary that it was wrong. But I didn’t know then what my options were. Having a script or some sentences cued up as an arsenal — like a self-defense harassment arsenal — I could have used that in that moment, and it would have saved me years of regret that I didn’t handle that situation differently,” Gordon told The Information.

A year later after the alleged incident, Gordon was let go from Mad Men and hasn’t written for a TV series since — a turn of events that caused a lot of speculation in the industry at the time, as young writers who win Emmys tend not to quit the business a year later and never return. After Gordon went public with her allegation, a spokesperson for Weiner said he “spent eight to ten hours a day writing dialogue aloud with Miss Gordon […] He does not remember saying this comment nor does it reflect a comment he would say to any colleague.” But Marti Noxon, who also wrote and produced for Mad Men and went on to create Sharp Objects and Dietland, said she believed Gordon because she was in the office the day after the alleged event, and labeled Weiner “an emotional terrorist.” Gordon has since founded the nonprofit Modern Alliance, which “collaborates with people and organizations across different industries to put an end to sexual harassment.”

Last month, Weiner seemed to walk his denial back a bit in a recent Vanity Fair interview tied to The Romanoffs: “I really don’t remember saying that,” he said of Gordon’s allegation. “I’m not hedging to say it’s not impossible that I said that, but I really don’t remember saying it.” He continued, “I can’t see a scenario where I would say that. What I can see is, it was ten years ago and I don’t remember saying it.” He added, “I never felt that way, and I never acted that way towards Kater.”

The Romanoffs episode doesn’t offer anything as concrete as Gordon’s allegations, Noxon’s statements backing her up, and Weiner’s denials for audiences to chew on. The episode is all over the place, and seems to be striving for evenhandedness, topped off with a philosophical shrug that says, “Well, what can you do? People are complicated and petty and self-interested, and it’s hard to be sure what actually happened in situations like this.”

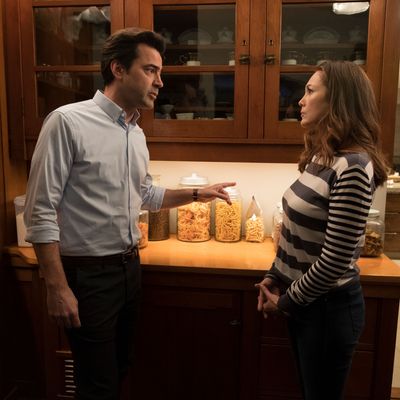

According to a police investigator who visits the episode’s heroine, Russian literature professor and Romanoff descendant Katherine Ford (Diane Lane), Rannells’s piano teacher David Patton might have behaved “inappropriately” toward a minor-aged student. Katherine and her husband Alex (Ron Livingston), a homophobe who unexpectedly ends up being the episode’s nearest thing to a voice of reason, let all three of their sons study with David. Their eldest, a college student, says David sometimes made off-color, age-inappropriate jokes but never laid a hand on him. (Like Alex, the boy agrees that David’s jokes were offensive mainly because he wasn’t funny.) Their middle child, an older teen who just participated in a recital overseen by David, considers him a great teacher and person, and is outraged by the accusation. Their youngest, an elementary schooler, barely seems to understand what David has been accused of at all.

Katherine isn’t sure herself, nor are the other adult characters, although a single vague accusation sends many of them spiraling into paranoia and catastrophizing speculation. The fellow piano mom suspected of starting the whisper campaign (Mad Men regular Cara Buono) seems like a Typhoid Mary–of–rumors type, but the episode confirms only that she’s freaked out by the accusation when she finally hears it from yet another parent. “Max had a lesson yesterday!” she tells Katherine after slipping into her car during a school drop-off. “Should I take him to a doctor? Should I have him examined, like everywhere?”

As for David, he seems to be guilty of nothing except being risqué around his students, fancying himself more charming than he is, and stealing other people’s stories (including one about the Romanoffs that he took from Katherine — the episode’s only connection to the series’ weakly developed unifying element, the notion of bloodline as entitlement). There’s also a narrative cul-de-sac in which Alex tells Katherine a story about his childhood friend Alan, who was accused of being a girl, told Alex he was a boy, and turned out to be a girl after all. Tied in with this are a couple of visually rhymed scenes where Alex and his father explain the apparent moral of the story to us as if we’re children. The camera briefly adopts the position of a listening child as if to make the episode’s bobbing-and-weaving brand of condescension part of its visual aesthetic. “When you accused somebody of something, whether they did it or not, you make everybody look at them differently,” Alex tells his sons. “Bearing false witness is the worst crime that you can commit. Otherwise, anyone can say anything about anybody, and just saying it ruins their life!”

There are repeated references to the teacher’s life potentially being ruined or destroyed by the accusation, should it move beyond their immediate social circle. Matthew Weiner’s life was not destroyed by Kater Gordon accusing him of an inappropriate remark, though he surely felt that way. His career wasn’t ruined, either. Amazon aired The Romanoffs anyway, and with “Bright and High Circle,” Weiner uses his show to genuflect toward ambiguity, contradiction, and the ultimate unknowability of truth. But certain tells give it away as a defense brief.

David, whose status as the accused artist/mentor makes him an obvious stand-in for Weiner, emerges as a force for good — a man whose positive contributions to the lives of his students and their families outweigh his unpleasant or misguided qualities. “In your heart, you have to stretch yourself, and make everything like it was,” Alex warns his sons, by way of apologizing for dragging them into a melodrama that besmirched the teacher’s name. Alex’s unaffected sincerity burns more brightly in viewers’ memories than his subsequent admission to Katherine that Alan was a girl after all, which neuters his dad’s righteous take on that childhood dilemma. More vivid is the scene where Katherine listens to a student reading Aleksandr Pushkin’s poem “When Your So Young and Faerie Years,” which describes a person “ … smeared by the gossip’s noise,” their “public honor fully lost.”

The mirrored gestures that begin and end the story — a door opening to reveal a piano recital, and another closing on David teaching Katherine’s youngest son in private once more — make it feel a bit like a fantasy of Weiner being spared the embarrassment of a public accusation, and permitted to go on practicing his art without having his name permanently besmirched. But the disquiet in Lane’s eyes in the closing scene confirms that it’s impossible to forget an ugly charge after you’ve heard it. All in all, it’s hard to come away from this episode thinking of it as an evenhanded thought experiment that lets us arrive at our own conclusions — though I can’t recall an episode of TV that gave us that kind of experience without also delivering vivid moments and powerful characterizations, elements in short supply here.

Beyond the episode’s weakness as both a drama and a polemic, it just feels unnecessary. As writer and producer, Weiner has already created seven seasons’ worth of anthropologically detailed analysis of sexual misconduct in the workplace with Mad Men. After having written a 2016 book about the series, I was anxious about revisiting it after Gordon’s charge, but it holds up because the writing never confuses complexity and contradiction with special pleading. There are no episodes where we simply don’t know what happened. There’s never any question about who holds the upper hand in terms of gender dynamics or workplace politics. The lead characters are allowed to be a lot of things at once, their nobility and awfulness coexisting without undue comment, as when Pete Campbell, a serial cheater who gets a secretary pregnant and sexually exploits an au pair, becomes a political voice of conscience during moments of historical trauma.

Rape culture is a looming presence throughout, starting with season one’s “Ladies Room,” in which a group of men forcibly test a deodorant on a male co-worker behind a closed office door by pinning him to a table in a mock gang rape, laughing the whole time (“Pretend it’s prom night,” one says) through season two’s “The Mountain King” — by Weiner and Robin Veith, the episode preceding Weiner and Gordon’s Emmy-winner — in which Joan is raped by her fiancé Greg Harris on the floor of Don Draper’s office, an act that Greg doesn’t think of as sexual assault because, on some level, he’s bought into the idea that wives are property. Don is a prostitute’s son raised in a brothel, where he lost his virginity to a sex worker in a rape that nobody there thought of as a rape, either. His wires are so badly crossed that, in both sexual dalliances and long-term relationships, he alternates between acting like a cold and domineering client, a sex worker subordinating his own wishes to the client’s tastes, a pimp pressuring others to use sex as a form of currency, and an orphan desperate to please a series of maternal figures who can never fill the void left by his mother’s absence. Throughout, we’re allowed to wish for the happiness or redemption of often-terrible people without retroactively excusing any of their deeds. Don in particular steadily falls as the series goes on, losing influence, trust, and respect of loved ones and colleagues right up until his ironic self-rescue at the very end, apparently creating the iconic 1971 Coke commercial that commodifies counterculture values. His enlightenment could be read as false, sincere, or both, but it’s preceded by an unambiguously abject phone conversation with his former secretary, protégé and confidant, Peggy Olson, listing his most painful failures through tears.

The dynamic between Weiner and Gordon is very Don-and-Peggy-like: the assistant becoming the student and, very quickly, the equal of the man who “discovered” her. Gordon’s accusation retroactively puts a new frame around many major episodes of the show, making it seem as if Weiner (solo or with co-writers) is working through scenarios that might’ve resulted in Gordon staying, and in nearly every case making the ad agency (a stand-in for Mad Men itself in this reading) seem like an increasingly more oppressive place for an ambitious and talented woman. Don rarely seems like the good guy in any of these thought experiments. The show lets us see where he’s coming from in a given scene or interaction, but without in any way suggesting that he’s right and Peggy’s wrong. It’s far more common for Peggy to come off seeming like the reasonable one, and for the show to condemn Don for failing to grasp Peggy’s unhappiness or appreciate her value to the company, or his own life.

Peggy’s continual and justified demands for more power, pay, and respect grate on Don, culminating in season four’s classic “The Suitcase” (solo-scripted by Weiner). It’s practically a two-character play in which a protégé eclipses her teacher, in the process accusing Don of accepting co-credit for an acclaimed ad he barely worked on. The dialogue contains exchanges that now sound like Weiner working through his feelings about Gordon, and not in a self-flattering way. And while Don’s pickled viciousness is explained by a crisis he’s going through, the episode never acts as if his private drama justifies his unprofessional and high-handed behavior toward his female employee. “I thought we were doing this at nine,” Peggy chastises him when he arrives late. “It’s 11:15.” “I’m late, but you’re not,” he says. “Good work so far.” And most famously, we see Peggy complaining that Don never says thank you for any of her hard work, and Don yelling, “That’s what the money is for!”

Season five’s “The Other Woman” — written by Semi Chellas, one of many Mad Men veterans who went on to work on The Romanoffs — now feels like a horrific sequel to “The Suitcase,” with Joan being pressured into sleeping with a car dealer so that the agency can land the Jaguar account. After consultation with a sympathetic Lane Pryce, Joan agrees to do it in exchange for a substantial bonus and a full, voting partnership, a first for a woman at that agency. Throughout, men who should have rejected the proposal out-of-hand are eager to entertain the possibility, because money’s what they value more than anything else. A couple of the partners seem to object to Joan’s acquiescence on moral grounds, when they are actually concerned about how much cash it might cost them. The lone holdout is Don, and it’s suggested (though never stated) that he angrily objects to the plan because it triggers memories of a childhood spent in a brothel. Here, as in many other episodes, the writing is keen in showing the psychological toll taken by this sort of exploitation, and how turning it into monetary gain is a Pyrrhic victory for women in such situations.

Joan might be thinking of the events of “The Other Woman” in season seven’s “Severance,” when she and Peggy pitch a pantyhose campaign to a couple of leering ad men from McCann Erickson whose inappropriate verbal remarks are as artless as they are crass. In the elevator ride to the street afterward, Peggy suggests that she and Joan have lunch, and Joan replies, “I want to burn this place down.” It’s a complete turnaround for their relationship, which started out with Peggy subordinate to Joan (the secretary to her office manager), and Joan often instructing Peggy on how to get along in a male-dominated workplace without making waves, because the ultimate goal was to get married and get out, not reform the place. Joan later responds to an inappropriate overture by a McCann Erickson colleague by going up the ladder to the CEO and threatening to file a complaint with the Equal Opportunity Employment Commission. But the story line ends in bitter compromise, with Joan selling her shares to McCann Erickson for half their value. (Even the percentage is meaningful: In 1971, women’s work was valued about 59 cents to a man’s dollar.)

It’s depressing to watch The Romanoffs obliquely address the Gordon–Weiner situation after having watched Mad Men deal in similar material over the course of seven seasons in much richer and more imaginative ways, weaving psychology, sociology, history, and pop-culture into the mix, creating a series of dramatically charged confrontations that never resolved themselves in a simplistic way. The worst part of it is that The Romanoffs seems spineless in comparison, retreating into “we can never really know what happened” hand-waving, and encouraging us to sympathize with the poor man who only wants to be “the key that unlocks the mystery of talent,” in another parent’s words — and a man whose life was nearly “ruined” by scurrilous talk, unbeknownst to him. We’re supposed to see Weiner in David the piano teacher, and realize that he was victimized where David was saved. But if you take the long view, there’s no way to buy any part of the analogy. Gordon reported an exchange that she says damaged her psyche and altered the course of her life, then left show business entirely, never profiting from her accusation, but instead dedicating her energy toward helping people who are in the same situation she claims to have struggled through. Weiner, in contrast, is the still-powerful creator of a landmark drama, and now he has a new show — practically a series of short feature films, shot in the United States and in Europe, with an all-star cast. That likely sounds like cold comfort to Weiner, but as Don would put it, that’s what the money is for.