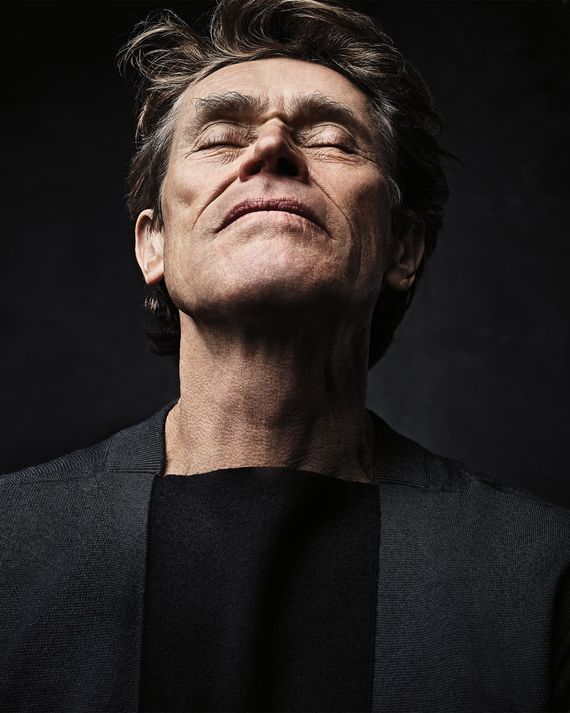

The actor Willem Dafoe and I knew each other back in the early 1980s, when he was already an outstanding actor at the downtown avant-garde Performing Garage and I was someone trying to be an artist — or anything — in that same growing scene. But we hadn’t seen much of one another before we sat down to talk about his riveting performance in At Eternity’s Gate, Julian Schnabel’s new movie about the last days of Vincent van Gogh, in which Dafoe plays the artist less as the tortured legend he has become in the popular imagination and more as the seeking, striving, ecstatic man he was in life.

Can I call you Willy?

You can call me Willy. Only certain people would always call me Willy. But I haven’t seen you in so long.

We started in the downtown art world together, two huge losers from the Midwest.

That’s true.

Do you remember I drove you and your son, Jack, home from the hospital as a newborn the day after he was born, in 1982?

I do. Crazy, crazy.

So I know you’ve spent a lifetime in the art world. What was your relationship to van Gogh before At Eternity’s Gate?

Pretty much like most people, even people outside of the art world.

What was he to you? Was it the romantic myth of the tortured artist?

I didn’t quite get him at first. I don’t want to brag and say I get him now, but through the film I have an intense relationship to his work now. One of the keys to approaching this movie was learning how to paint. That really changed how I see and specifically how I see his painting. I had to paint. We were shooting with a very fluid, loose camera. It didn’t make any sense at all practically. There was no cutting away before editing; there was no stunt painter. You see a lot of painting in the movie.

I love that process. It’s one of the most mysterious things you could see in the world, and this movie has a lot of that.

The most important thing was painting those shoes early in the movie.

I know all the works were re-created for the movie. It was you painting Shoes? I thought it was Schnabel.

The thing looks like shit for a long time. The colors look wrong. It’s not a likeness, doesn’t look like shoes, and then the marks accumulate and then boom — it becomes something. And it’s not a good likeness, but it captures the soul, captures the experience of those shoes, and the audience is there to see that boom.

Van Gogh is this amazing artist where you see the picture — the Shoes — and the marks of paint simultaneously.

I would say that’s fair.

And it’s almost miraculous how your mind is toggling between the two.

Yes. But that’s after some sort of training or experience. I always remember the first time Julian set me up. He just said, “See that cypress tree?” He said, “Paint that cypress tree.” I said “Okay.” I started to paint it, and I started to paint a tree and I was in a hurry to paint a tree. He came over, and he said, “Wait. You see those dark places, you see that black there — well, I don’t know whether it’s black, but you see that dark there, there, and there?” And he pointed out these areas, and he said, “Put that in.” I started to do that. He said, “You see that kind of yellow?” Where do you see yellow? I felt like a little kid — where do you see yellow? I started to do that, and I started to see it’s not about deconstruction. It’s about painting the light. That was a big impression. Maybe that’s A, B, C of painting, I don’t know. But for me — I’m not a painter, and coming to that was exciting.

In the movie, he talks about how the painting is there in nature. I don’t invent the painting; I just have to free it. That kind of looking at a tree — not running to call it a tree but seeing it as a swirl of vibration and relationship of marks kind of cracks open your sense of reality.

In what sense?

Sometimes you disappear into the action or you become part of the fabric of an activity or of a piece or a narrative or a picture. You know, it’s a quasi-religious experience. Then you come back to life. How do you reconcile those two feelings? How do you sustain that kind of sense of presence and engagement that you have sometimes through what you do and apply it to life? Not just to be a decent person but to be awake. That’s the main thing.

You know, in the movie they kind of grill him on this. “What do you think you can do?” Van Gogh basically says, “Wake them up to life.” “Do you think they’re asleep?” He says, “Yes, I do.”

I love that the movie changes our notion of van Gogh as a crazy man.

That idea of the tortured artist, that suffering is a prerequisite, is not something I feel comfortable with as I get older. When I was younger, yes, because you have to earn your sensibility. You often have to do that through some sort of crisis or duress. As you get older, I feel like grace is important, clarity is important. Conflict I’m not so interested in. I’m more interested in peace than anger now.

One oddity is you are 63. Van Gogh in the film is about 37.

Which I want to talk to you about because it pisses me off when people say this.

I thought I was the only one who noticed! And I didn’t even notice it until after.

I’ve heard it a couple of times because those internet trolls get on this shit. The truth is, think about it, Jerry. You’re a smart guy. I started thinking, 37, he was pretty beat-up. Thirty-seven in France in 1890. I did some research. I saw what the median age at death for men in France was at that time: 48. So he was not a young man.

I didn’t even notice it until preparing for this.

Also, I’m such a youthful 63.

You’ve played a lot of artists, oddly enough. I’m not going to count Jesus, but you played T. S. Eliot and—

Pasolini.

Pasolini in his last days.

When I was young, to say you were an artist was pretentious and a dirty word.

How so?

You come from the Midwest.

I know. I don’t come from art.

Artist was an elevated term for someone that was elite and operated in these circles of rich people. Your average blue-collar guy had no use for art because “My kid could draw that.”

You’ve talked about your brother taking a bullet for you: He became a surgeon, so you didn’t have the same pressure to get a real job. I was thinking about Theo and Vincent. Theo is in the real world. Actually, Theo works in the equivalent of the Gagosian Gallery. He’s an insanely connected man.

And van Gogh was not unknown in his own time. Far from it. Van Gogh is, in a way, the story of a poor and famous artist. Many, many artists in Paris knew every move van Gogh made. They didn’t necessarily love it, but a lot of them knew this Dutch guy was way out in front of the curve. It’s not a romantic story of a failure. Everybody knew he was pretty effing great.

And people don’t know that.

This movie begins to move the needle in the right direction.

I’m not sure the movie changes that so much, but Julian was very obsessed with that. Julian’s like, “He wasn’t unknown!” This thing about selling just one painting — he had contacts and people were talking about him.

You guys don’t make much of the ear cutting, which I also love.

Nor did he.

Nor did van Gogh.

He really said it was nothing. But for most people, that was the total proof that he was out of his mind, which is perfectly reasonable.

Absolutely. If you cut off your ear …

Not a good idea. I’m not going to do it.

Do you have a favorite van Gogh or two that you’ve walked off with in your heart?

Well, Shoes, because I didn’t have any relationship to them before and now I do. I also love the drawings.

Me too.

They’re so pure and they seem almost naïve, but they’re so wise and so clear that they aren’t showy. They’re beautiful, and to try to copy them—you don’t see it a lot in the movie, but I did practice those swirls of the cypress trees. For me, that brings you into another world. That is modern.

I think that is a top-of-the-line art-historical observation. I’ve often gotten mad. I think, Damn it, van Gogh, you’d already accomplished it in your drawings, you big dummy. It’s right there. You needed a little bit more time to absolutely work it out in your paintings. Although it’s in the paintings. Do you still go around … I used to see you in galleries.

It’s one of my favorite things. I probably learned more about acting from galleries and dance than I have from seeing theater or film.

How so?

Making marks. It’s all about an accumulation of actions that are an expression of your life. It’s not an interpretation. It’s not “We need yellow here, so I’m going to put yellow here.” It’s intuitive, and it’s a living thing.

*This article appears in the November 12, 2018, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!