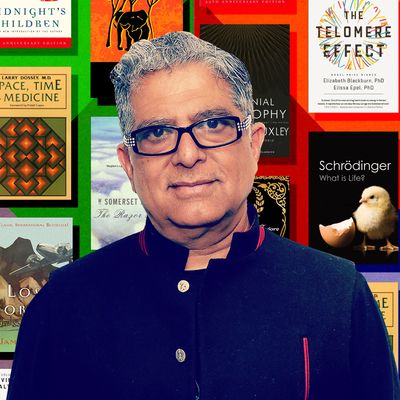

Bookseller One Grand Books has asked celebrities to name the ten titles they’d bring with them to a desert island, and they’ve shared the results with Vulture. Below is wellness author and speaker Deepak Chopra’s list.

An example of masterful storytelling that fascinated me growing up. I identified with Kim, the orphaned son of an Irish soldier, because we were both children of the army; my father was an army doctor who had served under Lord Mountbatten. On rereading, the setting of the Afghan Wars in the late Victorian era has chilling implications for today. The book is also a reminder that Kipling’s colonialist perspective didn’t blind him to the teeming human drama of India.

Another ripping yarn, from 1933, turning on the fantasy of a perfect world in Shangri-La. The British hero, Hugh Conway, was the first seeker I encountered in fiction, so that element must have struck a chord in a teenage boy’s heart. The book is all fantasy, mystery, and the smoke-and-mirrors of the exotic East. I don’t care and still love it.

The existential side of inner seeking, which appealed to another part of me as an adolescent. The war-traumatized pilot Larry Darrell was my first encounter with a character who walks away from conventional social life to find inner meaning. I suppose you could say that Maugham waves a sparkler at the start of the spiritual journey. Materialism and money-grubbing get a bashing, which is worth thinking about today.

If all the other books on my list were taken away, the one that would accompany me to the desert island would be this small book of inspired poetry by the great Bengali man of letters, Tagore. When translated into English, it won him the Nobel Prize in 1913 and made him an international celebrity. Gitanjali turns the spiritual life into a love affair between the poet and God, a theme that is thousands of years old. In my heart of hearts, I wish I was Tagore.

This book offers the best scientific guide to anti-aging and the perplexing question of why we age in the first place; in the future, Blackburn’s work on how DNA degrades over time could stand up as the key breakthrough in the field. The fact that Blackburn won the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2009 testifies to her important findings, but it is also a symbolic victory for all the women who did major historic work on DNA, brain chemistry, space exploration, and other fields without receiving their due.

The dystopian side of Huxley produced Brave New World, which foretold the myriad bleak worlds to come. The Perennial Philosophy is the opposite, perhaps the cure. In describing the common features of world spirituality, it outlines with clarity the transcendent strain in what humans aspire to become. Without a transcendent vision, I can’t imagine anyone’s life having deeply rooted purpose and meaning.

A living embodiment of Huxley’s Perennial Philosophy, Krishnamurti wrote many books about the need for modern people to wake up. As with Tagore, the horrors of World War II and the existential crisis of the Atomic Age dimmed Krishnamurti’s message, but he enjoyed a resurgence just before his death in 1986. He was sensationally glamorous to Westerners but relentless in confronting people with their lack of inner knowledge. The First and Last Freedom distills his teachings in a forceful, concentrated way. Few have taken such a stark view of the spiritual crisis in modern life.

A sensation — nothing less. This novel not only won the Booker Prize in 1981 but was honored as the Booker of Bookers in 1993. I identify with Rushdie’s imaginary echelon of children born at the stroke of midnight on August 15, 1947, when India was liberated. In its rich tapestry of storytelling, magical realism, and history, the book revealed Rushdie’s staggering talent. He turns the turmoil of India and Pakistan into a Tolstoyan panorama that is much funnier than War and Peace.

Fellow physician Larry Dossey made a risky leap in 1985 by applying the new physics to medicine (the book’s foreword is by Tao of Physics author Fritjof Capra). Mainstream medicine was still spooked and skeptical over the mind-body connection, and here was a doctor speculating on Bell’s Theorem and relativity, making connections between the quantum and the very basis of physiology. Seeing the human body burst into a cloud of subatomic particles thrilled me. No book has been more influential on my own writing career, and Dossey’s intellectual courage was an inspiration.

As celebrated as he was for his pioneering work in quantum physics — e.g., Schrödinger’s equation and the paradox known as Schrödinger’s Cat — What Is Life? sealed the great man’s reputation as a crank, mystical dreamer, and in some quarters, a traitor to science. This doom befell a small book from 1944 that, innocently enough, applies the principles of physics and chemistry to the life of a cell. What ruined the author’s reputation but came as a phenomenal breakthrough for me was that Schrödinger placed consciousness front and center in the phenomenon of life on Earth. It’s one of the most prophetic messages of all time.