In Vice, writer-director Adam McKay has devised a rollicking comic style for what amounts to an anti-hagiography, a scabrous portrait of Dick Cheney the Unholy One, cursed be He. The film tracks Cheney (Christian Bale under heavy but seamless makeup) from a young Wyoming screwup scolded after a second drunk-driving arrest by his brittle, ambitious wife, Lynne (Amy Adams); to a scarily proficient legislative power-monger; to, post 9/11, a global terrorist, bombing and torturing willy-nilly. The movie’s fulcrum — which is its prologue — is that day when TV monitors teemed with images of burning towers and Vice-President Cheney coolly wrested power from the stumblebum President G.W. Bush — airborne, out of the loop — to the unease of Cabinet officials. “He [wielded that power] like a ghost,” reads the opening titles, “with most people having no idea who he is or where he came from.” Acknowledging the intense secrecy that continues to surround Cheney, those titles close with the assurance that the filmmakers have “done their fucking best.”

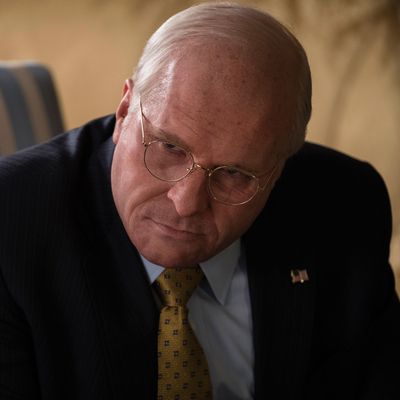

Their fucking best turns out to be pretty good, and in the case of Bale, pretty fucking great. Over the course of Vice, we watch Dick thicken into the Cheney we know, his jowls deepening, his head — too heavy for his neck — sinking into his torso. Bale’s rasp is raspier than his Batman’s, and he nails Cheney’s chilling half-smile, which curls so fluidly into a sneer that in the end there’s no difference. As impersonated by Bale, Cheney the Edifice is too impregnable for McKay to make it — psychologically speaking — past the moat, but the movie does have a firm dramatic arc. After Lynne instills the fear of impotence in him, Cheney finds himself amazed by men (it’s always men) who push their executive privilege. As an aide to Republican Congressman Donald Rumsfeld (Steve Carell), he catches a glimpse of Richard Nixon and Henry Kissinger with their heads bent together, planning the bombing of Cambodia. “That means approval by Congress,” says Cheney, to which Rumsfeld gives an impish smile: not exactly. McKay cuts to huddling Cambodian families as their village becomes an inferno, while Cheney, back in Washington, contemplates the attractive concept of the “unitary executive” — in his view (if not the framers’) meaning the president can bomb whomever he damn well pleases.

As in The Big Short, McKay stops Vice to teach us — with the help of a few guest stars — what’s what and who’s who and why what we’re witnessing is, from a constitutional perspective, so jaw-dropping. He also supplies a narrator, a young man (Jesse Plemons) who talks to the camera from sundry locales and whose connection to Cheney is withheld until the end, when we see him [REDACTED], and then, to our disgust, [REDACTED]. Not all the surreal jokes land. It’s amusing when Dick and Lynne plot their circuitous attack with breathless intimacy in the manner of Mr. and Mrs. Macbeth, but labored when they switch to actual iambic pentameter. (I love that McKay gave it a shot, but the idea could have been relegated to the DVD extras section.) It’s not so much the gimmicks but the performances that keep us laughing. Sam Rockwell’s George W. Bush — first seen falling down drunk on his father’s election night — is a likable fellow driven to impress his dad and serenely untroubled by his own cretinous: The wheels in his head turn at slightly under half-speed. Carell, so dull in his serious role in Beautiful Boy, once again displays his genius for caricature. His Rumsfeld is a popinjay so dazzled by his own aperçus that he can only watch dumbly as the single-minded Cheney charges past him.

Vice has a big structural problem, though. However fitfully inspired, the narrative doesn’t hold you, and by the time McKay arrives at the vice-presidency, the audience is a little tired. The movie settles into a series of journalistic flash cards: Now Cheney cherry-picks intelligence for the Iraq war, now he helps select the one lawyer (John Yoo) who will establish a legal basis for torture (i.e., “enhanced interrogation”), now he watches from afar as the minor Islamist he demonized in an attempt to convince the American people of Saddam Hussein’s links to Al Qaeda ends up (his fame bolstered by the U.S.) leading the Iraqi insurgency. McKay handles deftly the reductio ad absurdum of Cheney’s fearsome power: the televised apology of the man Cheney shot in the face at a hunting resort for inconveniencing him, Cheney. Watching these blackout sketches one after another, I began to long for scenes with more dramatic heft, and for a protagonist with more wrinkles. There are a few, chiefly Cheney’s unshakable love and support for his lesbian daughter (Alison Pill) in the face of his base’s homophobia — although even these are a setup for a shaking down the road.

It’s an original brew, this movie, with a score by Nicholas Britell that’s deadly serious even when the film is at its zaniest. Because it is deadly serious, however big the laughs. I winced a bit at McKay’s use of Cheney’s multiple heart attacks as punch lines. (Look out, here comes another one!) But given that he holds Cheney directly responsible for the deaths of thousands of American soldiers and hundreds of thousands of Iraqi civilians, it’s hard to work up much indignation. For McKay, Cheney’s diseased heart is a metaphor. He even presents it on a steel table after a graphic surgery sequence, in all its ugliness. He must have wished he’d had Smell-O-Vision to fully convey the rancidity.

Vice was nominated for eight Oscars in 2019, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor, Best Supporting Actor, Best Supporting Actress, Best Original Screenplay, Best Makeup and Hairstyling, and Best Film Editing.