Bookseller One Grand Books has asked celebrities to name the ten titles they’d take to a desert island, and they’ve shared the results with Vulture. Below is New Yorker journalist and author William Finnegan’s list.

Among all of Orwell’s great unflinching reportage, this book stands out as a personal odyssey and first-person witness to history. He went to Spain in 1936, during the civil war there, to help fight Fascism. He joined a leftist militia and found himself targeted not only by Franco’s forces but by Stalinists intent on crushing anyone not toeing the Moscow line. Orwell’s descriptions of wartime Barcelona and impoverished rural Spain, his clear-eyed analysis of the shifting factions in the war, are triumphs of tender, hard-headed participant-observation. He was wounded at the front, shot through the throat by a sniper. His peerless moral grasp of the dangers of totalitarianism began in Spain.

Like Orwell, Twain is better-known for his canonical fiction, but he was also a genius of observation, and this early work, which is broadly nonfiction, about his early career as a riverboat pilot, is my favorite. It’s not uproarious, like “Roughing It,” but it dives deep into its milieu. “The face of the water, in time, became a wonderful book — a book that was a dead language to the uneducated passenger, but which told its mind to me without reserve.”

The best of the Nathan Zuckerman novels, and that is saying something. The story rewinds several times, postmodern-style, and each retelling is a distinct, sometimes shocking alternative to the previous narratives, and yet the novel’s grip only tightens. Harrowing, funny, sexy, set in England and Israel, New York and New Jersey, altogether splendid.

The first volume in the Neapolitan quartet, this one changes in the mind’s eye if you’re pulled, as I am, helplessly through the subsequent books, with its primal scenes from early childhood deepening throughout. Is there a better portrait of friendship in literature than the story of Elena Greco, the narrator, and her brilliant friend, Lila Cerullo? Elena escapes the old neighborhood, and the poverty of postwar Naples, through education, but Lila remains the incandescent figure. The tormented power of their relationship never flags, through “The Story of a New Name,” “Those Who Leave and Those Who Stay,” and the devastating “The Story of a Lost Child.” I hear the TV series is good. The books are a universe.

The language sizzles and hisses in this 2011 Irish novel set in a steampunk future. We slip from the Trace, all tangled alleyways, to the Fancy, which is as it sounds, and even out to the wastes of the Big Nothin’, from which the Bohane river crashes down through the city. There’s a gang war, indelible characters, a martial music. Sweet Baba Jay, did anyone ever really speak this way? It’s wordplay at the level of Nabokov, but with a very different, Gaelic purpose. “Fucker Burke and Wolfie Stanners set their face against the hardwind as they climbed the bluffs.”

This is cheating because it’s four books in one. But Liebling wrote so well about so much, a compendium is merited. Two of these are reporting from World War II, where no other writer, in my opinion, could touch him. “The Road Back to Paris” is an epic dispatch full of hard times and the finest lyricism. The other two books are about France, food, wine, memory, boxing. I wouldn’t argue if you insisted that Liebling’s greatest subject was actually New York City, or even Louisiana. It’s too bad there’s not a 12-pack.

“The waves fell; withdrew and fell again, like the thud of a great beast stamping.” Woolf’s strangest book by far, a cascade of gorgeous monologues, six friends meeting over the course of their lives. The characters emerge through their voices, through the eyes of the others. Each suffers separately. Loss, loneliness, depression vibrate on the page, among the indelible images, all within a frame of stunning brief descriptions of the sun’s passage and the sea’s pounding. It’s partly the twilight of the British Empire, but mostly a brooding meditation on language and love. Bernard, the writer, delivers the great summation. Nothing happens except life.

Invisible Man has become something of an invisible book. It’s an American masterpiece and a pure, if searing, joy to read. Published in 1952, it dramatizes the doubleness of black life in America in a raucous, outrageous saga, as its unnamed narrator makes the Great Migration north to New York. “I am invisible, understand, simply because people refuse to see me.” Its brilliance is distinctly mid-century, though, and Ellison, once a Marxist firebrand, became an arch elitist, doing his book no favors with his disdain for popular struggles around race and inequality. But the vitality of Invisible Man is undiminished, and its most caustic insights into American life still painfully relevant.

The most piercing, most beautiful sea tale I’ve read. Told almost entirely through dialogue — through Caribbean dialect, no less, where “Captain” becomes “Copm” — with the sparest possible narration, as precise as haiku, and pictographs, inkblots, great tracts of white space on the page. Nine working men set sail on an old schooner out of Grand Cayman, hunting green turtles. They talk to fill the ocean silence, their speech unattributed, and the drama circles and tightens. “Green turtle very mysterious, mon.” The characters sharpen into high suspense and tragedy. Matthiessen’s touch, his ear, his eye, his taut presence just outside the story’s frame — all miraculous, mon.

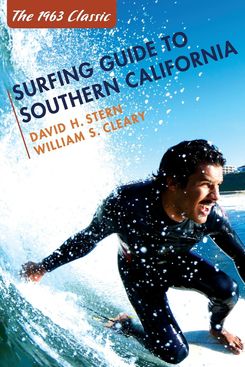

First published in 1963, and never updated, except for the tide charts, this is a true guidebook. It tells you where to park and how much you’ll pay (in 1963 prices). Mainly, though, it’s about waves, and how to describe them clearly and accurately. At least, that’s what I loved about it as a kid, and still do. It covers several hundred surf spots between Point Conception and the Mexican border. The Namib dryness of its photo captions never ages.