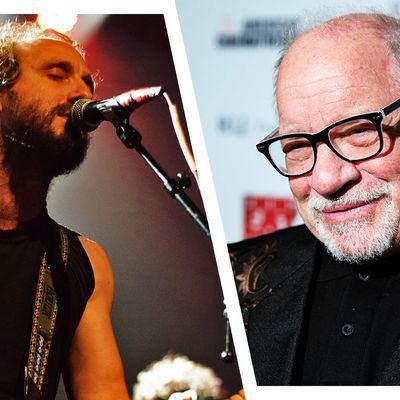

Writer and director Paul Schrader — who wrote Taxi Driver (1976) and Raging Bull (1980) — is one of Hollywood’s great character artists. His best films portray tortured individuals struggling for redemption in a world without easy answers. Last year, he wrote and directed First Reformed, about a wayward priest (Ethan Hawke) unraveling in the face of metaphysical demons. Schrader wrings humanity and humor from his protagonist’s darkest moments. It is nominated for an Oscar for Best Screenplay.

It makes a certain amount of sense that he likes to bang out scripts while listening to Phosphorescent, the long-running project of Alabama-born singer-songwriter Matthew Houck. Over the past two decades, Houck has released seven albums of lilting indie rock accented with country twang. His lyrics tend toward finely wrought sketches of love and loneliness. In October, he released the surprisingly upbeat C’Est La Vie, his first record in four years. Houck recently became a father; after a career defined by melancholy melodies and heartbreak narratives, he sounds cautiously happy.

The director called up the musician for a conversation about music, drugs, suicide, religion, and the struggle for creative independence.

Paul Schrader: So, a couple years ago, when I started writing First Reformed, I was playing what I call “iTunes pool,” where you get up late at night and start caroming from one song to another. And I stumbled upon Phosphorescent, and I was very, very taken by it. It’s become my go-to writing music for three scripts now. There was a period where I cheated and went over to Zola Jesus for a while.

Ezra Marcus: What is it about the music that helps you write?

PS: There’s a kind of hypnotic otherworldliness to it that gets into your bones. So you’re not really listening too much, but it’s still nourishing you. They have this thing — my mother would have called it caterwauling — where they have several voices, which are slightly dissonant and discordant, and most pronounced in a song called “Wolves.” I love that. I wanted to ask, Matthew, how did you come to that technique?

Matthew Houck: [Laughs.] I think that’s what my mother would call it, too. From the beginning, I always worked by myself to make these albums. And about three records in, I realized, I started wanting to have more harmonies, and background singers, and choirs. So I started doing it myself. [Now] I feel like it’s not really a Phosphorescent album if I don’t do that layering of vocals.

PS: I want to ask about one of your earlier songs, “Joe Tex, These Taming Blues.” I never understood what that title meant, because Joe Tex never made a song called “Taming Blues.”

MH: No, but on that record there’s a horn break that I stole directly from a Joe Tex song called “Buying a Book.” So I just lifted it exactly and decided to send that song out to him. “Taming Blues” is about being tamed by love, or the need for it.

EM: What did you think of First Reformed?

MH: I was blown away. I think it’s the best movie I saw this year. Paul, I wanted to ask about the part where it goes psychedelic, when they levitate. That’s where it took off into my favorite kind of movie.

PS: Well, I knew I wanted to get to the other reality that’s right beside us. Sometimes it feels like you can reach out and touch it. I thought to myself, while I was sitting at my desk, What would Tarkovsky do? And I thought, Tarkovsky would have them levitate. That’s what he always does. I said, Well, if it’s good enough for Tarkovsky, it’s good enough for me.

It begins in an Edenic environment, like the first panel of Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, and then it moves into the present moment. Finally, his mind is so polluted that he takes this Edenic revelation right into the underworld, into the dark place.

MH: Have you had a lot of experiences with psychedelics in your life?

PS: There was a period where I wanted to make a film about ayahuasca, but not too much. A little bit here and there. But I am actually quite frightened of myself. I had some close calls with self-harm, and I just didn’t trust myself not to do something truly stupid. I wasn’t clearheaded. I did have one pull of Russian roulette, and that was enough to convince me that I needed help.

MH: You’re kidding me.

PS: Yeah, in the Jacuzzi in Los Angeles.

MH: That’s the craziest thing I’ve ever heard.

PS: I was with some friends, and they called my psychiatrist. It’s around 1 in the morning, and he came over to the house, and we had a long talk. He said, “I have to take the gun.” Ten years later, I’m back in Los Angeles, and I said to myself, I wonder if Dr. Madison is still practicing. I look him up, and sure enough, he is. I make an appointment, and I go over to his office. I said to him, “I don’t know if you remember; there was an episode in my house, ten years ago, with a gun.” He said, “Oh, I remember. I have the gun right here.” He opens the drawer and he has my gun. He said, “I’ve always kept it in the drawer to remind myself what I’m really doing.”

MH: Wow. Did he give it back to you then?

PS: No. [Laughs.]

MH: I agree with that about psychedelics. I think they’re pretty amazing tools. There are definitely planes that are not this plane. There are probably a lot of ways to access them, but my first glimpse was through psychedelics. It’s something you can’t unlearn. But I also have that level of fear.

PS: When I was in college, I was trying to get a girl to go out with me. I said to her, “You have to say yes to me, or I’m gonna jump out this window.” And she didn’t say yes, and I jumped out the window. As I was falling, I thought to myself, God, that was stupid! Some of us need minders.

EM: Paul, in a recent interview about First Reformed, you described yourself as thinking, “It is time to write that movie that you swore you would never write.” Can you elaborate on that?

PS: I was a child of the church and the church education, and I rebounded. I got involved in secular, profane, longer entertainment, and I never thought I would circle back around, and then three years ago it probably occurred to me that it’s time to write that script that I’ve been running from my whole life.

MH: It seems pretty clear to me that [the film] is critical of religion. You’re setting out to show the warped-ness of it.

PS: Yeah, but it takes the spiritual struggle very seriously. It does not make light of that. Most films do; most films don’t really get at what men and women of faith can go through, and what drives them.

MH: Right, you make him a protagonist. So did you stay religious, or did you get out early?

PS: Well, I didn’t get out early. I went all the way through Calvin College, which was a seminary. And then I went to UCLA grad school and went to Los Angeles in 1968. And that’s where the break occurred, and there was quite a break from Grand Rapids to Los Angeles in 1968. About five years ago, I got back in. I started out as Christian Reformed, then I moved over to being Episcopalian. Christian Reformed is all the guilt and none of the ritual; Episcopalian is all the ritual, none of the guilt. And now I’m over with the Presbyterians, which is a little bit of both.

MH: [Laughs.] Yeah, they all seem to lay pretty heavy on the guilt part. I was raised Presbyterian actually.

PS: But you were raised in Alabama. Presbyterian in Alabama’s different than Presbyterian in New York.

MH: I think you’re right. The South has its own way of dealing with those things. My grandfather was a Presbyterian preacher, so [religion] was just a steady fact of life. It was so omnipresent that you could actually ignore it. It was just how things were. I became disillusioned with the whole thing around my late teens. I think it’s a beautiful thing, the search for this higher thing. But it’s so obviously flawed and its caused so much horror in the world. Seems hard to bring it all back together.

PS: Well, I like that quote from John Lennon. He said, “I don’t like God much once I get him under a roof.”

MH: That’s exactly it.

EM: Paul, I was wondering what you thought of C’Est La Vie.

PS: Well, C’Est La Vie is a definite change in tone from the earlier albums. There’s a sense of a horizon; there’s a sense of an opening. Some of the earlier songs were quite dark, and I like that, too. I can’t say C’est La Vie is an improvement just because Matthew is happier.

MH: Right! I think you’re hearing something that a lot of people hear. I know a lot of the early stuff was awfully bleak, and I know that I am obviously in a more stable or less anguished place in my day-to-day life. But the weird thing is, when I was writing this record, it felt almost exactly the same as those records that everyone thought were so dark. I don’t know if it’s all completely in my control, what things emanate from what you make. I guess you have a pretty heavy degree of separation with a movie?

PS: One of the real challenges is trying to leave room for the mystery when you have such a logistical enterprise, and so many people, and so much money. At some point you have to say, I don’t know why he does this, but he does it. If you answer all those questions for yourself, you take something special away.

MH: So how do you do it? You’ve still got to convey a sense of purpose to everyone who’s working on your film.

PS: There’s a sense of, “We’re going to do this, and I’m not sure why.” One of the things in this film First Reformed is, I don’t move the camera. So that becomes a rule. No panning, no tilting, no camera moves. But then, once you make a rule, you get to be the first one to break it. You have to break it, because people will forget you made it unless you break it. So one day we’re shooting, and a weird, weird shot came in my head. I said to the DP, “Let’s lay some reel. It’s time to break a move right now.” Why that morning? I didn’t think about it in the car on the way there. So you can still have that spontaneity that you have in songwriting, where a word pops into your head.

MH: Yeah, that’s me. The logistics of making a film — which is something I would truly love to do — seem showstoppingly difficult. It’s amazing to me that they get done at all.

PS: Yeah, it’s definitely an alpha practice.

MH: I’ve been lucky enough to not have a label that is over me saying, “Yeah, this,” or, “No, this.” How much time do you spend having to explain what you want to do to a higher-up?

PS: You spend most of your time groveling for coins, right? You’re like a kind of stray dog, going from tabletop to tabletop, grabbing crumbs that fall. And eventually you get your film made. You have to wake up every morning and say, “Nobody wanted me to do it. Let’s go try to do it.”