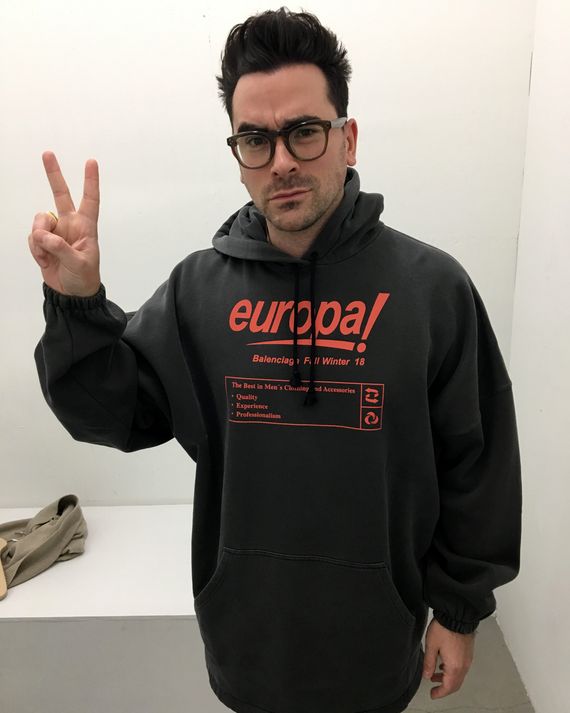

“Here’s what I think we should do,” Dan Levy says as he leafs through a rack of Balenciaga, selecting an oversize matte gray hoodie with “europa!” emblazoned on its front. “We should lean into the moment here, because this is the kind of thing people come here for.”

It’s a December morning and we’ve been wandering the freshly opened Dover Street Market in Los Angeles, a single-level fashion maze outfitted in an old warehouse, with brick walls painted gallery-white and a distracted funhouse layout housing various lines of Comme des Garçons, Prada, and Gucci. Part art installation, part sartorial playground, this is clothing less as a matter of practical exigency and more as a multisensory experience. There are no fewer than five, equally chic salespeople offering us water or assistance.

“I say we do just a full fashion look,” he continues. “Label whore-y.”

Levy gives me a glance I’m familiar with, at once amused and slightly conspiratorial, his lips curling like a scroll. It’s a restrained version of the unbridled facial reactions he delivers playing David Rose on Schitt’s Creek, the sitcom he co-created with his father, actor and comedian Eugene Levy. Or the look he once gave a puzzled Larry King when the octogenarian host asked him to explain pansexuality on television, clearly tickled by the whole situation. It’s a mouth on the precipice of social collapse.

Levy pulls on the Balenciaga hoodie and a pair of black fleece sweatpants, the label’s name, VETEMENTS, crawling down the left leg in an all-white, all-caps font. (Total retail price: $1,730 before sales tax.) It’s the kind of look that feels like an overpriced hug.

“Is this my new vibe?” he asks, considering himself in the dressing room mirror. “David would wear these sweatpants for sure. Just letting people know that you have money.”

Levy comes to Dover Street Market to scout for clothes for Schitt’s Creek, but buying off the rack is wholly unrealistic for his budget. “Fourteen episodes of our show is comparable to what one single episode of a bigger-budget blockbuster show costs,” Levy explains. Not to mention, the look isn’t period appropriate. The story of Schitt’s Creek revolves around the once-wealthy Rose family — the father, Johnny (played by the elder Levy), the mother Moira (frequent Levy scene partner Catherine O’Hara), and their two kids, Alexis (Annie Murphy) and David — who find themselves bamboozled and bankrupt, with all of their assets repossessed save for their considerable wardrobe — and a small town called Schitt’s Creek that David’s parents bought him as a gag gift, where they’re forced to move when they lose it all.

“We have dated it back to when they lost their money. Vetements would not be around at that time,” he explains. So, back to the rack.

“This sweater is a David Rose sweater for sure,” Levy says, eyeing a black sweatshirt by the Japanese label Undercover emblazoned with the words “Human Error” and an image of an astronaut floating into space. “If it wasn’t $800, I’d pick it up.” For the show, he typically has a $200 cap for any single item.

Even aside from its budgetary constraints, Schitt’s Creek is unflashy and modest. Its low-key, idiosyncratic weirdness isn’t far off from the mockumentary style pioneered by Eugene Levy’s frequent collaborator Christopher Guest, where the absurdity comes less from the situation than it does from the characters. Now on its fifth season, Schitt’s Creek was a critical hit in Canada when it first aired on CBC Television in January 2015, but it has been a slow burn in the U.S., where it premiered on Pop TV a month later. The turning point came when it debuted on Netflix in January 2017, where it has enormously expanded its die-hard fan base (known, of course, as Schittheads).

Schitt’s Creek is Levy’s first major creative endeavor, and his sole focus in life above basic subsistence (mostly pizza): He writes and executive produces and recently directed the show’s first Christmas special. And while there are echoes of Guest, and his father, in the work, what has been distinctly Dan Levy about Schitt’s Creek is its willingness to let emotional moments stand. The Roses are blithely self-involved, but they’re also people who are learning to love, and be loved. “We’ve never been scared of going there in terms of sentimentality, because we’ve never considered the show to be a comedy,” says Levy. “In our minds, the show is a drama that happens to involve funny people.”

Schitt’s Creek began as a partnership with his father, but since the second season, Levy has taken over as showrunner. And like every first-timer, he’s a bit neurotic about it. He has a hand in every aspect of production and post-production, runs the writers’ room, attends every wardrobe fitting, pores over edits, and plans marketing and promotion. He’s especially meticulous when it comes to the clothing, trolling consignment apps like The RealReal and eBay throughout the year.

“I buy most of the clothes myself,” Levy says as we glide past Comme des Garçons shirts with bunny ears attached at the shoulders. “I need to touch things and feel them. Wardrobe was the first in terms of me understanding the characters and what they were about.”

On set, Levy is like a helicopter parent buzzing around his first child. When the cast and crew returned to set to shoot the fifth season of Schitt’s Creek, which premieres on Pop TV on January 16, he immediately noticed that two things were amiss about the motel room where the family lives: one, the beds were made differently (they were hospital-tucked, and the duvet wasn’t covering the pillows), and two, there was a slight crack in a ceramic wall relief of a swan. The fracture was too slight to be visible on camera, but still, he knew it was there.

He knows he’s OCD. “It’s a blessing and a curse,” he sighs. “I just don’t think I’ve ever taken the opportunity for granted. I still feel like I’m trying to earn my place in the game.”

Levy was not born in Los Angeles, a decision that was not made lightly by his parents, Deborah Divine and Eugene Levy, while he was in utero. At the time, they were living in L.A. for the elder Levy’s acting career. “This is around 1980, and there just was a vibe,” says Eugene. “A showbiz vibe. Is it a fair environment to your kids to raise them in a cloistered social scene? Are they going to have a chance to do other things that might not fall under the showbiz umbrella?” They decided to move back to their former home, Toronto, “even though it would probably not be beneficial to me.”

“Cut to: both kids end up in the business,” Eugene laughs.

The family kept Eugene’s acting career separate from Dan and his younger sister, Sarah (who also stars on Schitt’s Creek as the good-natured town waitress Twyla Sands); still, Eugene’s stature in the comedy world — first established with the renowned comedy troupe of Second City TV, followed by his collaborations with Guest — was impossible to ignore. “I wasn’t necessarily aware of what my dad did, but I was aware that wherever we’d go, there would be attention. I was never comfortable with it,” says the younger Levy. “I was always very reluctant to lean on him for anything, because I did feel like if I was going to explore the entertainment industry, I didn’t want to feel like I hadn’t done it on my own.”

From an early age, Levy gravitated toward writing and acting. In sixth grade, he adapted the teen fantasy novel The Hunter’s Moon into a “lovely Gaelic romp” and played the Faerie King; during a teacher’s strike in high school, he and some friends staged a production of Clue, which he adapted as well (starring as Mr. Green). Once, when they were putting on a revue during high school, his father suggested that he reenact a sketch that he had done in his SCTV days. While Dan was practicing the part, Eugene tried to offer feedback. “I said, ‘Well, I performed this onstage. I know what the timing is.’ No, no, no. I’ve got it, don’t need your help, thanks,” Eugene remembers his son saying. “We go to see the play and we’re so nervous because we really have never seen him do anything in public. He came on and did the scene, but as a Keanu Reeves impersonation. He was giving it his own spin. I remember saying to my wife, ‘He’s actually got something!’”

In college, Levy pivoted to film production, in part because he was too self-conscious to go into the dramatic arts. He was an introverted kid and lacked the confidence to go out for auditions. He also felt his father’s legacy looming over him. “When you grow up with a parent who has made such an impact outwardly, there is a fear that, ‘What if I don’t have what it takes?’” he says. “It was a long time of really pushing away his input to make sure that I had my own point of view and skill set.”

A few months before graduation, Levy applied to be a VJ for MTV Canada, where, eventually, he would host The Hills: Live After Show and The City: Live After Show, beginning his journey of combing the lives of the rich and thirsty. Over the course of eight years at MTV, he built an audience in Canada and name recognition independent from his father. His curiosity about the ultrawealthy became the premise for Schitt’s Creek: Levy wondered what would happen if a stupid-rich family lost their fortune and had to move to a small town they had bought (a premise drawn from that time Kim Basinger bought the town of Braselton, Georgia). He knew he wanted it to have his dad’s comedic sensibility: the kind that celebrates weirdness — like having two left feet — and doesn’t marginalize anyone for it. “I would like to think that our show is an example of being able to keep an edge while at the same time putting something positive out into the world,” says Levy. “That sensibility came from my dad. His comedy was always left of center. He never wanted to do anything on the nose.”

So he asked his dad to create a TV show with him. When he came to him with the idea for Schitt’s Creek, Eugene cycled through a series of emotions:

First, excitement. “I would have said yes no matter what the idea was,” Eugene says. “The idea of working with my son on anything is just too good a thing to pass up.”

Then, wait, this could be a disaster: “Very early on, after a couple of days of brainstorming, I had woken up in a cold sweat at night thinking, Boy, what if he doesn’t have it? What if there’s really not much talent there? I was afraid I would be faced with that dilemma of, do I actually have to sit him down and tell him I don’t think this is something you should be pursuing, or do I just continue on this project knowing it’s not going anywhere?”

And finally, relief, mixed with pride: “Fortunately, he pretty much out of the gate showed that he had great prowess as a writer.”

They had to ease into a working relationship. Eugene learned to give his son space to execute his own vision, and taught him not to rush the prep work. “I felt I had to mentor a little bit because this territory was foreign to him,” he explains. When he stepped into the role of David for the first time, he had some notes. Levy spoke in a hushed whisper, and reacted a lot with his face; his father told him to speak louder and make it all feel bigger. “I remember being like, ‘Okay. I’m good,’” Levy recalls. “Which, I’m thinking to myself, the man has 40 years experience, you probably should have listened. But it worked out. I spoke a little louder. We found that happy medium.”

Five seasons in as showrunner, Levy gives his actors feedback sparingly. “Very few ideas are better than Catherine O’Hara’s ideas when it comes to acting,” he says. “And very few notes are better than what my dad has come up with in a scene.” But this is still a job in which, sometimes, he has to tell his dad what to do. Eugene remembers one moment in particular from filming the pilot. Levy walked over to him at the end of a scene. “He said, ‘I don’t think you’re going to be happy with that line reading. Maybe try and lighten it a little bit. That might help,’” Eugene recalls. “I said ‘okay,’ and at first I’m thinking, Wow, it sounded pretty good to me, but I did what he suggested, and of course, that was the way to go. That was a little moment where I thought, This kid really knows what he’s doing, here.”

“Yup, mhmmm,” Levy says, nodding at a black motorcycle jacket sitting atop black ruffles like piped frosting on a cake. “The answer’s yes to this.”

We’ve come upon a section of Noir Kei Ninomiya, a protégé of Rei Kawakubo’s, and the clothes are instantly Moira: pure black Japanese architectural fashion, both tough and cool.

“And this,” he says, pointing at an ensemble of a black chiffon skirt with straps over the torso like a thick capital “H” over a white shirt with a Peter Pan collar. “Moira has been a dream, because Catherine is such a chameleon,” he says. “Clothes, wigs, shoes, strange tights, hats. We realized, Oh, she can pull off anything.”

In Schitt’s Creek, the clothes are one of the last remnants the family has of their former life: Johnny, often the straight man, wears proper Zegna jackets; Alexis projects a cool-girl-at-Coachella vibe in gossamer-thin Isabel Marant dresses; Moira has an astounding collection of wigs and clothes pulled from an avant-garde Japanese fever dream; and Levy’s former New York City gallerist David is a true Rick Owens acolyte.

When Levy steps into a Rick Owens outfit, it telegraphs something about who his character is on a cellular level. The tunics and drop-crotch pants are an outward manifestation of his dark romanticism and stubborn streak of individuality. They’re the kinds of clothes that swaddle the body in amorphous and ambiguous folds; they screw up gender expectations, much like David himself.

In the first season, the show introduced David as pansexual by way of a wine metaphor. (Hence the Larry King interview.) Stevie (Emily Hampshire), the hotel manager who has an immediate kinship with David, asks what kind of “wine” he likes. David explains that he partakes in all wine — red, white, rosé. He cares about the wine, not the label. “A lot of people’s snap judgments on David was that he was gay, and when he hooked up with Stevie, everyone was sort of thrown,” says Levy. That was intentional: Levy wanted a character who could move beyond the limits of “masculine” or “feminine.”

“What I hope is that [David] can stand as an example for the fact that you can have certain characteristics that might be seen as ‘feminine,’ which to most people mean queer qualities, and still be attracted to women,” Levy says. “Masculinity involves feminine qualities and femininity involves masculine qualities. It’s getting rid of the rules that people have put on us all, which has been quite a burden to many.”

Growing up, Levy was bullied for being “effeminate.” He was shy and thoughtful and into fashion then, too. “When you show signs of perceived feminine qualities in the schoolyard, you were called gay, you were called ‘lady-boy,’ you were called ‘fag.’ All of that happened,” he says. “Was it to the extent that a lot of people are sort of having to endure across North America? No. Was my life ever in danger? No. Did it still affect my confidence and make me question my sense of self? Absolutely.”

Home was a refuge, and coming out as a gay man to his family was smooth. “My mom asked me one day at lunch in a very lovely and respectful way. I was finally comfortable enough to say yes, I was gay, and it really was never talked about again,” he says.

Levy’s vision for Schitt’s Creek is a reflection of those values, where love and acceptance are givens. And as much as his father, the actor and comedian, has influenced the show’s tone, Schitt’s Creek is also in part a study of the Levys themselves. There’s an assuredness that courses through the show, starting with the love between Moira and Johnny. It would be easy for the dynamic of a riches-to-rags couple to descend into sniping and finger-pointing, but their relationship is a firmament on Schitt’s Creek, much like Levy’s own parents’ marriage, which he describes as a “strong, successful relationship that was never in question.” Or, as O’Hara simply puts it, “Daniel’s humor comes from love. There’s a love and respect for his characters in his comedy.”

That’s apparent in the romance between David and Patrick (Noah Reid), one of the most poignant on television. As with David, Patrick’s sexuality is ambiguous until the season-three finale, when the two kiss and Patrick tells David he’s never kissed another man before. Levy finished writing the scene just hours before shooting, reading the lines to Reid over the phone. Originally, it’s Patrick who kisses David, but after talking about his own first gay kiss with a friend the night prior, Levy realized their dynamic would make more sense if David took the initiative. “I’m telling a story that I would want to see as a teenager. I try not to let expectation get in the way of the clarity of the storytelling, but I was feeling the responsibility of getting it right and sharing an experience that people have had in their own lives, and not fucking with a really meaningful moment,” he says. “You know, everyone remembers their first kiss.”

The scene is pure, heart-tugging romance, the kind of ugly-cry moment that’s only possible if you have a large emotional investment to cash in on. It’s also punctuated by a dash of sharp, Levy-ian wit — David ends the scene by telling Patrick he’s not a morning person.

“The David Rose sense of humor is a sense of humor that we as a family have,” says Sarah Levy. “I’ve grown up with [it] my entire life so I’ve actually become desensitized to how bizarre his jokes are. I have to realize that people are discovering now what I’ve been living with for 32 years.”

Levy changes back into his everyday clothes — a tan sweater, ecru-colored jeans, and tartan chucks. Stylish, but not overly opinionated. He used to wear more Rick Owens when he was younger — his first major fashion purchase after he got the MTV job was a trademark Rick leather jacket (which he also happens to wear in the pilot of Schitt’s Creek) — but has done it less as he’s become more known for the role of David Rose.

“I once wore those black Rick Owens lace-ups out, and someone on the street was like, ‘Do you wear your costume outside?’ I was like, ‘I had them before!’ Now I guess I can’t wear them anymore,” he laughs.

We stroll down the street to a nearby café for lunch, a catchall place with wood-fired pizzas, salads, quinoa bowls, green juice, and eggs. The food is still something Levy is adjusting to in L.A., where he migrates in the winters to escape the Toronto cold, and it isn’t until he asks for a side of bacon that he realizes we’ve entered a vegetarian café. “I see right where we are now,” he says, looking around. “I haven’t embraced the Los Angeles lifestyle. The healthy lifestyle — highly active, clean eating. None of those things appeal to me. I’ve indulged my child’s palette for way too long.”

He’s trying to enjoy his newfound success in Hollywood more though, such as by attending the Critic’s Choice Awards, where Schitt’s Creek was nominated for Best Comedy — a first for a Canadian production. He tells me he has his outfit planned for the festivities: a Burberry tuxedo in a shimmering cobalt blue jacquard. He tried it on recently, and it’s admittedly a little tight for comfort. “I have been hiking and doing push-ups and sit-ups, and trying my best not to eat as many pizza slices as I normally do in a week,” he says. “I’ve ordered two Spanx T-shirts, just in case. You gotta do what you gotta do.”

But with attention comes its attendant stress. “The bigger the show gets, the higher the expectations. The higher the fear that things have to be perfect,” says Levy. “It’s a lovely, vicious cycle of stress and anxiety.” In many ways, the modesty of the show — that it was on CBC, the smaller budget — insulated Levy, in the beginning. He had the time and space to do the creative work outside of the highly pressurized bubble of ratings and social media, including thinking about how Schitt’s Creek is going to end, which Levy says he already has plotted out. And while he has loved working with his father, he has some solo projects in mind, including a pilot script for a half-hour dark comedy about a troubled feminist writer.

“[Writing the script] was a great opportunity to face the inevitable,” he says. “When you have a success very early on, there’s always the fear of, do you have another one in you?” He feels a similar wave of fear at the beginning of every season of Schitt’s Creek. At first, he thought the current season, the show’s fifth would be its last. “Any time you go back into the writer’s room, I always sort of panic and think, ‘What are we going to say this season?’” he says. “Inevitably, we get there, and the experience is great.”

His mind wanders back to fashion. “I can imagine it would be very similar, where you have a collection every six months. Now it’s like 15 collections a year and you’re thinking, like, ‘What? How do you keep telling stories?’ Yet you do.”

*A version of this article appears in the January 21, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!