First Reformed is like nothing Ethan Hawke is famous for. The hero in Paul Schrader’s movie about religion and corruption and the environment isn’t greasy and flirtatious or artfully disheveled; he’s not even funny. He’s desperate and jumpy, holding everything inside. Reverend Toller’s faith in the church has decayed somewhat, but he’s also got an epic case of mania. Toller pastors a small church — more of a somber tourist destination than a place of worship — and journals despairing, guilty pleas to feel God’s presence. When he’s asked to counsel an environmental extremist who’s about to become a father, the pastor stumbles upon a cause where he can channel all of his malaise.

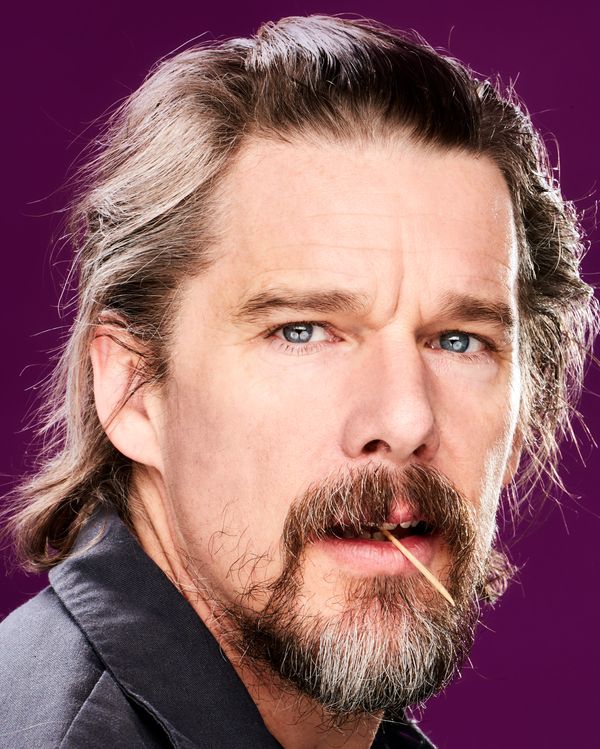

Hawke has been acting for 30 years, but says Toller gave him more of an opportunity than any job he’s ever taken. “There aren’t very many times that I’ve felt that connection to a role the way that I did this one,” Hawke told Vulture as he drove on the FDR to rehearsals for True West, the Sam Shepard revival he’s starring in opposite Paul Dano. “Often, I’ll get a great role, like in True West or in Tennessee Williams or Shakespeare, but it’s been played a lot before. There’s been other interpretations. But when you get a great role in a movie, it’s a wonderful challenge, because you can define it yourself.”

Hawke’s performance is hard to shake: In every scene, it’s like Toller is wearing an invisible straitjacket. He spends much of the movie not even trying to remedy the moral corruption he sees in his own neighborhood and his own soul — he’s just trying to make sure everyone else acknowledges it. Toller has earned Hawke the best reviews of his career (or at least the best reviews since the last Hawkaissance, for Boyhood). In long, loose loops, he told Vulture about the movie that’s earned him trophies from Gotham, New York Film Critics Circle, and Los Angeles Film Critics Association for Best Actor — and maybe even his fifth Oscar nomination.

Do you remember how you felt the day before First Reformed started shooting? Were you nervous?

Paul had asked me — it was kind of a complicated, meticulous, weird thing — to write out all of Reverend Toller’s journals. He sent about 50 journals to the house, ‘cause he wanted one to have one journal entry, and then one book to have two journal entries, and one book to have three journal entries, one book to have four journal entries. I kept having to rewrite the journals over and over again, ‘cause he wanted them all in my handwriting. He wanted to be able to show okay, in this section of the movie, if I want to see the journal, I want half of them written, I want three-quarters of them written … So I had to have basically somewhere between 30 and 50 journals of different lengths. I spent all of the Christmas holidays doing these journals. I would have never recommended it in an acting class or something, but it was a strange thing to have to do to help you find your character’s voice.

It’s strange when you work with somebody who others call legend — you never know if they’re going to be interested in collaborating, and you never know what the experience is going to be like. When you have ideas that you think could help a script that’s written by somebody who’s writing level is so high … It doesn’t matter if you’re in rehearsals with Tom Stoppard or Sam Shepard, you still have to have your own opinion. That’s what they hired you for, you know? But it’s very hard to voice your opinion when you have a tremendous amount of respect for the person you’re working with.

So I remember I was confused about what the collaboration was going to bring. I’ve been acting for more than 30 years now, and there aren’t very many times that I’ve felt that connection to a role the way that I did this one.

Can you tell me why?

First off, I come from a long line of very serious Christians. My family were Quakers who came over on a couple boats after the Mayflower. My grandparents and my mother and my father are all extremely religious people. There’s a slight scowling glance that might sneak out in regards to when a young person says they want to pursue the arts, you know? ‘Cause he might be choosing to live a frivolous life, that might be their first assumption.

I see a real connection between that life and the artistic life. The artistic life tends to function at its highest when its really deeply connected to an awareness of your own inner life, whatever that word means. You study great painters, or great poets — W.H. Auden or Egon Schiele, Nina Simone — artists at a great level tend to connect their work to something spiritual.

Did working on this make you reconsider your own faith or spirituality?

No. I think what a great writer does when they’re on their game is give voice to something a lot of people are feeling. There’s a tremendous amount of anxiety in the air, a lack of political and spiritual leadership. Fear collects in your chest.

Even working on True West right now — Sam really writes a lot about the masculine war with itself on a personal level. When it’s amplified, it’s exactly what we’ve done to the whole world. Beating up women, beating up the female part of ourselves, beating up the planet, beating up Mother Earth. All that stuff is very much on Shepard’s mind as he writes about these self-loathing men. A lot of men’s only manifestations of masculinity is their wallet or how many people are afraid of them, you know? And that’s not leadership.

Something I really like about your performance in this is that Toller’s physicality feels so limited. I think of it as a sort of manic restraint. Can you tell me how you arrived at that?

One of the first times I had coffee with Paul, in regards to this movie, he asked me if I knew what a recessive performance was. And I did. Most performances are trying to entertain you, to capture your imagination, thrill you, make you curious, make you laugh, make you cry. A recessive performance avoids the audience. If it works right, it draws you in and invites you in, and lets you participate, because it doesn’t tell you what you’re supposed to think all the time.

For Toller, it invites you into his inner mania, as you said. I think that’s really well put. On the surface, he has to create a feeling of everything being fine. Inside, there’s kind of an Edvard Munch–like scream happening all the time.

Was it uncomfortable to live in that for the whole shoot?

Oh, yeah. It’s always a challenge. You don’t have a movie like this without really looking hard into depression. I think Paul’s writing and work has some clear insight, whether it’s Taxi Driver or First Reformed, it’s been a long time with him meditating on depression and on a fraudulent society. Just ‘cause you’re depressed doesn’t mean you don’t have clear-sighted insights into others.

I want to go back to those journals he had you write. Do you journal yourself?

I did, meticulously, every day, from when I was about 16 until I was about 44. And then — it’s kind of a funny story, but it’s true — someone stole my journal.

What!

Like at an airport, yeah. About five years ago. I left my bag for a minute, and somebody went in my bag and stole my journal. It freaked me out. We live in such a weird time where it’s like, Oh my God. I’m going to have to read my journal on the internet. This is going to be hugely embarrassing.

Remember when that would happen in high school? Somebody’d keep a journal and somebody’d read it out loud in the lunchroom or something, just humiliate another person. Well, I was just incredibly petrified of who this person was that stole my journal. And I just stopped keeping a journal. I tried to start again, but I have not been able to do it. One funny thing that is different today is that we write so many emails that all of my emails to my friends turn into de facto journals. But I miss my journals.

But you still have all the other journals?

I still have all the old ones.

Do you ever reread them?

I haven’t in a long time. When you’re going through really hard times — when I was in my early 20s, and when I went through a divorce — a journal is incredibly helpful to make sense out of your thoughts. Sometimes your thoughts need to be controlling you, and keeping a journal helps you understand how much you’re repeating yourself, how much you’re … I don’t know. I’ve always found it extremely helpful.

I’m at my childhood home right now, and I came across my high-school journals the other day — I can’t bear to read them.

I know. It’s scary, isn’t it? I found my journals the other day from Explorers.

Oh, wow.

I know. I literally have these journal entries about how River’s getting on my nerves. It’s really weird.

I’d like to talk about two scenes in First Reformed that really took me by surprise. The first is when Toller and Mary float through the earth and space and the cosmos. What was your read on that moment?

It’s so clear how lonely he is, that simply being near a kind woman gives him some ecclesiastical vision. Thomas Merton was this great Catholic writer, and a lot of the hippies liked a lot of what he had to say, ‘cause he wasn’t as dogmatic as a lot of the great Catholic thinkers. Joan Baez came to visit him, and she was barefoot. He hadn’t seen a woman’s foot in like 20 years or something. He writes in his journal that he couldn’t take his eyes off her foot. He’s trying to be serious and talk to her, and address her concerns about politics and Vietnam, but all he kept thinking about was her foot. I thought about that when she’s asking him to touch her hand. Toller basically levitated, you know? That’s how good it felt.

Also, it prepares you for the end of the movie: There’s kind of another spiritual plane that the movie’s happening on that isn’t exactly naturalistic.

The other scene is when Toller sits in the office with Jeffers, the pastor at Abundant Life. All of Toller’s anxieties come to a head: “Well, somebody has to do something!” There are a lot of good memes of that moment.

I haven’t seen them, but there should be memes to that. Who hasn’t felt that way? Can’t somebody do something, please? Isn’t someone in charge with a brain in their head?

That’s the one place where I pushed outside the box of what Paul wanted me to do in the movie. Rules are made to be broken, and even Paul agrees with this. If I’m doing a recessive performance, at some point he has to explode out of his little box. I can go back in the box, but that was the moment where the cracks show.

Is there something that you appreciate about acting now that you couldn’t, or didn’t, when you first started?

A little slows down, you know? When you’re young, there’s a slight sense of desperation, of wanting to be noticed, of wanting to be seen, and wanting to believe in yourself. For some reason, the movements of it all has slowed down as I’ve gotten older. I’ve enjoyed it a lot more.

There’s an expression they have at Juilliard called, “Let your habit not be your only choice.” I really love that expression, because if you slow down enough and break your habits, you can see choices, paths, that you didn’t see when you were rushing. And that is certainly one of the advantages of getting older.

When did you notice that you’d started to slow down in your process, that you weren’t rushing in the same way you used to?

I did this play, The Coast of Utopia. It was a Tom Stoppard play. It’s actually nine hours long about these mid-nineteenth-century Russian radicals. We did it at Lincoln Center for nine months, and it was a lot like going back to grad school. I was in my mid-to-late 30s, and I was surrounded by a large group of people — Billy Crudup, and Josh Hamilton, and Jennifer Ehle, and obviously Tom Stoppard and Jack O’Brien. A lot of the cast was extremely good. We were in a community for a long period of time, and sometimes it’s in seeing how other people work, being close to it.

Somehow, some kind of adult relationship to acting started there. Martha Plimpton was one of my friends when we were children actors, and she was there. Checking in with her, and feeling what her experiences had been as a woman, and what parts of our passions had remained, talking about the friends we’d lost and the friends that are still around, who’d given over to bitterness and who was getting smarter — you watch your own generation, you know?

That was a very pivotal experience for me, I think. I had three very pivotal experiences with the director, Jack O’Brien. He directed me in Shakespeare’s Henry IV, in Coast of Utopia, and then Macbeth. I would say those three experiences pushed my growth as an actor more than anything else I can directly identify.

Ministry is a vocation — “many are called, but few are chosen,” and all that. Do you feel like being an artist is your vocation?

Definitely. I definitely feel that way. I don’t know if you ever saw it, but I made this documentary called Seymour: An Introduction, and one of the things that I’ve come to believe is that when people ask themselves that question about who am I — a very difficult question to answer — but one of the ways in which we can answer it is with what we love. And the closer you are to what you love, the more time you spend inside that love, the more what you love opens up and becomes bigger and expands, and you expand. The more time you spend away from love, away from what you love, the less you grow.

It’s just like water and light, you know? It sounds a little airy-fairy, but it’s not rocket science. It’s pretty simple. You take care of yourself. I think that how to define taking care of yourself is to put yourself in a position to be near people you admire, work that you admire, freer thoughts. From the Bible: “Let the words of my mouth and the meditation of my heart be acceptable in thy sight.” It’s something to aspire for. None of us are there. Very few of us are there.

For me, making movies, doing plays, helping other people make movies and do plays, righting wrongs, being in it, helping … Trying as much as you can not to give into the great pull to just celebrate what makes money. ‘Cause, you know, crack makes a lot of money, too.

That’s a funny way of putting it.

It’s true! People think just ‘cause the movie makes them money it’s good. Or just ‘cause a restaurant makes money, it’s good. Or just ‘cause a person makes money, they’re good. It doesn’t mean they’re bad, but it doesn’t mean they’re good, either

You’ve been promoting First Reformed for eight or nine months now — has your perspective of it changed as you’re talking about it so much?

The movie’s really about hope and despair. It’s hard not to have hope when a little tiny movie as dark and incendiary as this one is finds an audience. Paul and I did a Q&A at Brooklyn Academy of Music a couple days ago, and we looked at each other, like, we’ve been doing Q&As for this movie since May. This doesn’t happen. It just doesn’t happen very much at all, especially without somebody spending a lot of money to push you forward.

I have a great sense of gratitude around it, that it’s still in the dialogue. I’m as surprised as anyone. I thought when they decided to release it in May that we were headed for the lost aisles, streaming into the void. When they make that decision to release the movie in the spring, it generally means that they’ve made a decision that you’re not going to be a part of the end-of-the-year dialogue. So it’s kind of awesome that we’re here.

Does the awards-season stuff feel grueling? How do you keep perspective in this time?

It would feel grueling if I felt like I was selling. One of the things that’s hard about making commercial movies is that you have to sell it. But when you’re making a movie that is as personal and radical and strange as First Reformed, it doesn’t feel like you’re selling. It feels like you’re sharing, and it has a different energy around it. The whole thing — even the way you talk to me about it — is different than the way that you would talk to me about the fun of shooting Magnificent Seven or something, which was really fun. But it’s got a different goal.

I really like the way you talk about celebrity and art and this industry. I’ve sort of pitched this to my editors, that I want you to have a Vulture column.

[Laughs.] How’d you get the name Hunter?

My parents just wanted a unisex name. They didn’t want to know my sex before I was born.

It’s a really cool name. I’ve never met a woman named Hunter before, and I really like it. My wife’s name is Ryan. She’s always actually explaining to people who call that she’s a woman. But Hunter’s a cool name, and it’s a great name for a woman because … what’s the god? Dionysus? The god of hunting is a woman. I always forget her name. It might be Athena, for crying out loud. But anyway, I remember thinking it’s really interesting that the god of hunting was female. She protects the animals and is cool.

I can’t wait to use that as the story from now on — “Actually I’m named for the god of hunting.” Just one last question: Have you ever heard of Hawkecast, the Ethan Hawke podcast?

God, no. Really?

So there are a couple guys in Boston, and they go through all of your movies, and just talk about you all the time. It’s fun.

Well, I already love these guys and think they’re brilliant.

I’m sure they would love to hear that.

There’s a great James Joyce line. He’s asked what he expects from his reader. He says, “A lifetime dedication to his work.” I always thought that was funny.