Those who go into Dan Reed’s Leaving Neverland expecting a sensationalistic, data-dump exposé about Michael Jackson might be surprised to discover something quite different. Over the course of its four-hour running time, Reed’s film — which premiered at Sundance on Friday and will show on HBO this spring — focuses intently and intimately on the experiences of Wade Robson and James Safechuck, two men who say that Jackson sexually abused them for years, when they were children. Reed takes his time, however, interviewing these men and their families, giving them the space to soberly detail their experiences.

We’re so used to the fast cutting of contemporary documentaries that seeing one that allows its subjects to speak at length has a rather bracing effect: It gives us the chance to look into their eyes and decide if we believe them or not. The film’s extended running time also allows Reed to explore areas of the story that might have gotten short shrift otherwise. Among those interviewed are Safechuck and Robson’s mothers, who eagerly took their kids to see Jackson and who, despite some initial concerns, seemed to willfully ignore what was going on. Now, years later, the men still seem to have trouble forgiving their moms for not protecting them at the time. Indeed, the most powerful part of Leaving Neverland comes in its closing half-hour, when, years after Jackson’s death, Robson and Safechuck finally open up to their families about the abuse they suffered. An ordinary-length film would not have been able to include all that.

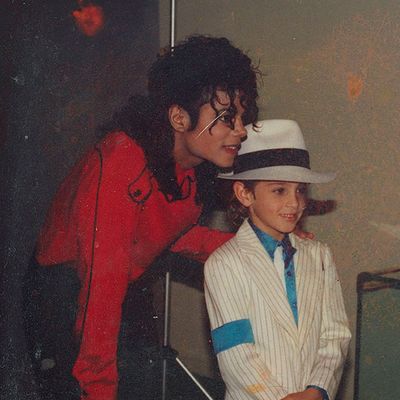

Safechuck met Jackson through a Pepsi commercial they appeared in when he was 8, and Robson met the singer after he won a Jackson-themed dance competition in Australia at the age of 5. Both kids eventually became very close friends with Jackson, with their families invited on trips around the world and extended stays in the superstar’s condos and estates. And even though their moms would often accompany them on these trips, Jackson made sure that the parents stayed in separate rooms or guest houses while their kids stayed and slept with him in the main house and bedroom. Robson and Safechuck also say that Jackson gradually tried to drive a wedge between them and their families. In Robson’s case, this may well have contributed to the breakup of his family, as he, his mom, and his sister all moved to Los Angeles, leaving behind his father and his older brother back in Australia.

The specific sexual allegations include fondling, mutual masturbation, oral sex, and more, and the men spend a lot of time in the film going into the acts in detail. In one of the more disturbing scenes, Safechuck describes a litany of sites around Jackson’s estate — bedrooms hidden from sight, located in unlikely places, often behind multiple doors — where he and the singer had sex. He also recalls that Jackson once “wed” him in a mock ceremony when he was 10, giving him a fancy diamond ring. The singer, he says, often plied him with jewelry in exchange for sex. He still has the box of jewels Jackson gave him; his hands tremble when he shows it for the camera.

At the same time, these children believed that they loved Jackson, and that he loved them back. There were candy and toys and videos everywhere, and tons of things to do. The singer helped them with their careers, bringing them along on tour and letting them perform. When he and Robson were apart, Jackson called and sent faxes all the time, his messages filled with affection and praise.

Robson and Safechuck are still struggling to reconcile their feelings for Jackson with their knowledge of what was done to them, it seems. As Safechuck says early on, “He was one of the kindest, most gentle, generous people I’ve ever known. He helped me with my career and my creativity. And he sexually molested me for seven years.” Robson, for his part, actually testified in Jackson’s defense at both of the singer’s sexual molestation trials — the first time eagerly, the second time reluctantly, he says — and only came out about his own abuse in 2013.

I spoke to the film’s director, Dan Reed, about the allegations, and about how he approached making Leaving Neverland.

How familiar were you with the Michael Jackson story before you started making this film?

Not at all. I make films about conflicts and terrorism and crime and stuff like that, and I have no real interest in show business or all those kinds of stories. I made a film called The Paedophile Hunter which was thematically linked to this one, but completely different in content and style.

When you decide to tell a story like this, what kind of verification do you do to confirm that your subjects are telling the truth, or that you believe them?

One factor, which plays a big part, is my 30 years’ experience of interviewing. I won’t claim that I can always tell when someone’s lying or not, but you do get used to catching people out when their account is inconsistent, or when there are jumps and flaws. The way I imagine it is that when people sit down and tell a story, their mind is looking at a real thing that happened to them, right? And that real thing is a 360-degree solid thing. So, at any one point you can turn them back to that thing, and they can reinterrogate it and tell you something new about it. They don’t have to make it up. When people are lying, they don’t have that thing — unless they are pathological liars. So, the technique of the interview is important: the length, the consistency, the sustained engagement with particular scenarios and questions, and approaching them from different angles and going back.

That comes through in the film. The viewer feels like we are in the same room with them the whole time. You don’t do a lot of clever cutting around the interviews. You really let your subjects speak.

I take great care with the filming of interviews. I’m sort of obsessed with exactly how it happens, and I prepare for a long time for the interview and study them. These are stories told by the human voice. And I like to make that as intimate and as immersive an experience as possible, and that involves the way you treat the sound and the cinematography and all that. But that’s just a means to an end. What I’m trying to achieve is to basically lock you in a space with these people, and for you to absorb all of the nonverbal signals — just the way we relate to people when they’re telling us a story. I want viewers to experience that in the theater or watching on TV. The films are incredibly simple: It’s just interview, aerial cinematography, and a bit of archive, you know? But it’s always amazed me how much drama there is in the face of a person telling you a story.

What are some other ways you verify these stories?

We have to make sure that their accounts stack up. That they were in, you know, Budapest when they claim were, and that Jackson did play a concert where he claims this happened, that sort of basic fact checking, which we were very diligent with.

I also interviewed experts on child sexual abuse. “Does this match the pattern of a pedophile?” A hundred percent it does. I went to see an LAPD detective specializing in child sexual abuse who’s been involved with more than four thousand investigations. And he said, you know, Jackson’s modus operandi was absolutely typical, and kind of cookie-cutter perfect. I mean, there is no videotape of Michael Jackson having sex with a child. We don’t have that kind of proof. Although he did record himself having sex with James …

Oh, he did?

Yeah. He destroyed it — he panicked and destroyed the tapes. But I believed [Wade and James] because their accounts have all the characteristics of a credible account. This wasn’t a half-hour conversation. This was days and days of interview, followed up by lots of checking up and verifying. And I haven’t found anything that made me question whether they were telling the truth or not. And I’ve got to know them pretty well now.

Did you reach out to other victims, or other potential victims?

I did reach out to those who I thought might be open to speaking to me. There are a number — some of whom are referenced in the film — who are staunch Jackson loyalists and have made that very clear on social media and all that, and there’s no point reaching out to them. But before very long, it became clear that this was a story about the Robsons and the Safechucks. This wasn’t like a series of generic stories which I used to demonstrate Jackson’s guilt. This really is sort of two family epics, and the completeness of the telling of each one is I think what gives the film its power and coherence. And as soon as you start adding more variety, you dilute that.

Because it’s not really a story about how two boys were sexually abused by Michael Jackson. It’s really a story about how these two men and their families came to terms with the fact. The denouement is the last half-hour of the film. Everyone’s focused on the acts of abuse, because there’s this story around Jackson — did he do it, or not? — but the story we tell in the film is actually about coming to terms with something that happened a long time ago.

At what point did you realize that would be what the film is about?

As soon I had the Wade and James interviews, and then definitely as soon as I interviewed [their mothers] Stephanie and Joy, I realized that there’s so much story in here, and it’s kind of epic. I did go interview detectives and D.A.s and people who had been involved in the criminal trial, and also people who had been involved in the [1993] Jordan Chandler investigation. It took a lot of time doing that, and it was part of the preparation for understanding what went down over those two decades. But then I realized that the drama is all in the families converging on this point where they find out the truth.

The Michael Jackson allegations have been around awhile, but there doesn’t seem to have been much of an effort to engage with them in recent years. And most people don’t know the details. So it’s like the story hasn’t been told, and yet there’s the sense that the story has been told. Did that pose a challenge for you?

That’s probably one of the main reasons why I chose to do the story, because it exists already out there as a question. And I think we’ve delivered the answer to that question. I’ve spoken to a lot of people, and there are two responses when I say I’m doing this film about the victims of Michael Jackson. One response is, “Oh, but he never had a childhood.” And that really annoys me. Just because you didn’t have a great childhood doesn’t mean you can rape children. And the other response is, “Yeah, I always assumed he was guilty, but …” And yet you still were happy to listen to his music … So, it was never settled, I think mainly because Jackson was acquitted in the criminal trial [in 2005], and that sent a big message. People were like, “Well, maybe he’s just really weird.”

I think in some ways maybe the reason why people don’t want to think about whether he’s guilty is because it requires way too much emotional and brain power to process this. Entire generations grew up with his music, and his image. You can’t take his influence out of world pop culture.

No. And that’s why I think people will come out of the film feeling sad. I think most people who take the trouble to watch the film will come out believing Wade and James’s story. I think it’d be very difficult not to believe them, once you’ve listened to them and their families. Imagining that they’d make that story up is just so implausible. But you walk away and it’s a sad moment, because another nice thing about the world has gone dark — the lights have gone out on a whole center of your cultural space. And it’s part of this era where we’re suddenly having our eyes opened about all sorts of people to whom we looked up. Institutions that we thought would always be there to protect us are being challenged. It’s a time of reevaluation.

Why are people so interested in the truth about what this man did in the late ’80s and early ’90s? I think it’s because of his presence in the fabric of American life and people’s lives worldwide, the fact that he means something to people. And the meaning of that thing is going to change, and we’re attempting to change it.

At one point, James produces a box of jewelry Michael Jackson gave him, which includes a ring that Michael gave him when they had a mock wedding, when James was 10. It’s a devastating scene. I’d never heard about this.

James’s story hasn’t been told at all. Jackson had this thing, where he would say to James, “Sell me some.” And that meant James would have to perform sexual favors for Jackson in order to get jewelry. And it’s interesting that he’s hung onto those rings. That was a scene we filmed later, actually. It took a while for James to come around to being able to show us those rings. Luckily, we were able to take such a long time making the film, which was partly because HBO and Channel 4 had the patience to wait for us to do the job properly. And when we shot the scene, as he says in the film, his hands are trembling. Those rings encompass or embody the whole story — the beauty of the ring and the value of it, and the abuse associated with it.

And the fact that he’s kept it.

And the fact that he’s kept it. They both say, “How do we deal with the fact that Jackson was amazing, that he had this incredible influence on our lives …” and played this mentoring role. Even if it was self-interested, he did have an impact on their lives, some of which they cherish. And yet, he also destroyed something very precious: their childhood. They’re struggling with it —James probably more than Wade is really struggling with that duality. The rings kind of symbolize that for me. I think it’s a really telling scene. You really feel for him. The mock wedding with a 10-year-old. I mean, come on.

There are a lot of people out there who are convinced that Michael Jackson is innocent, and have produced reams of counter-arguments against some of these allegations. Have you engaged with any of those arguments?

I’m familiar with the arguments. I know the reasons why they think that Wade’s lying, and none of them have any validity. It’s just not factual. We know he took the witness stand in 2005 and said that Michael hadn’t abused him. He says it in the film, and he explains exactly why that happened. We know that he went to Michael’s memorial service and wept. He says that in the film. You know, the fans were like, “Oh yeah, but he wanted a limo to go to Michael’s funeral.” Yes, it’s in the film. He doesn’t deny any of that. I have never come across anything on any of the fan sites or anywhere else that sort of caused me to doubt what Wade is saying. You know, if someone wants to make an argument as to why he’s not telling the truth, they should watch the film, and if they still think they have questions then, you know, I’d be happy to hear from them.

Was there ever a point at which you thought you might tell a more straightforward, investigative story?

I left that option open pretty much until we began editing, or a little way into editing. Because I wanted to be sure that I understood the civil case and the criminal trial. Because that’s where Wade reconnects with Jackson, is his testimony. He’s witness No. 1. He is the strongest witness in Jackson’s favor. He’d probably say this himself, but, as a fellow victim, he betrays [Jackson accuser] Gavin Arvizo by testifying, by saying a lie on the witness stand, and I think he feels badly about that. I wanted to make sure that I understood exactly what happened in that case, and why Gavin Arvizo lost the case. I wanted to make sure that I had all my facts straight.

Did Wade ever reach out to Gavin?

No.

Did you reach out to Gavin?

I did, yeah. I wrote him a long letter. He didn’t respond. He’s entitled not to respond, and I didn’t take offense to that at all. You know, this is a story which I feel will continue in my filmmaking career, because there are so many other avenues that I didn’t explore, other victims. And I would like to tell the story of the 2005 criminal trial, and I’d love to tell Jordy Chandler’s story from the inside. And that would require Jordy and Gavin to come forward. I did reach out to Gavin, because you have to keep your options open as a filmmaker with this kind of story, until really it’s impossible for you to make the film any other way than the way you’ve made it. And I felt that’s what we’ve done. It’s a story that demanded to be told in this way.

Are you surprised that more hasn’t been done about this story, until now?

I’m kind of astonished that this film hasn’t been made before. I think that as Wade said on stage [at the post-screening Q&A], you can only come to terms with it when you’re ready. I think the timing worked out, and I came along at the right time, and HBO was the right channel. I think what we’ve done is extraordinary and unique, and it’s never been done before. And it’s due mostly to the courage of Wade and James and their moms and their families speaking out. But also being able to let them tell their story over a long time. And to tell the story in a way that is the complete opposite of the disposable stories you get online — all of the, you know, two-, three-, and four-minute stories. This is the antithesis of that. And that’s why I think it has the ring of truth.