One of the worst deficiencies of the comics industry has been and continues to be its failure to employ black women. Historically, that demographic has been completely shut out of mainstream sequential art, even on stories about black female characters. That problem is in the early stages of being remedied, and Nnedi Okorafor is part of the solution. Okorafor doesn’t exactly need comics — she’s an acclaimed and successful writer of sci-fi and fantasy prose novels such as Who Fears Death and Binti — but comics certainly needs her. Luckily, she’s been offered to readers in a growing number of comics narratives. First came a short story in DC’s Mystery in Space, and subsequently, she’s helmed series such as IDW’s Antar: The Black Knight and various Black Panther–related titles for Marvel, including Black Panther: Long Live the King and Shuri.

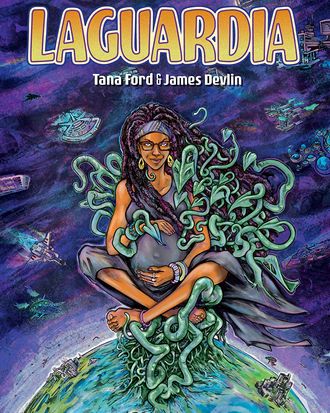

She shows no signs of slowing in her comics journey: She’s currently writing about the Black Panther character Shuri in an eponymous series and, perhaps more important, is penning a creator-owned series called LaGuardia for editor Karen Berger’s Berger Books imprint at Dark Horse. LaGuardia explores a near-future world where aliens have made first contact with an Earth that generally fears them — with the exception of Nigeria, the one country that has welcomed extraterrestrial immigrants. However, as the title suggests, New York’s LaGuardia International Airport (here rendered as LaGuardia International and Interplanetary Airport) receives visitors from other worlds, albeit with a great degree of uneasiness. The Illinois-based Okorafor is of Nigerian descent and uses LaGuardia as a platform to explore notions of dislocation and integration, aided along the way by the rich artwork of Tana Ford and James Devlin. We caught up with Okorafor to talk about her complicated relationship with the real-life LaGuardia airport, her problems with Black Panther’s native Wakanda, and her lifelong love of “Garfield.” Yes, that “Garfield.”

How did you first get exposed to comics?

For me, the way I was introduced to comics was a little different. I never felt very welcome going into comic-book shops. You know in Westerns where they have that moment when a stranger walks in and the music stops and everyone looks and there’s a clear sense that this person is not from here and we don’t really want this person here? That was the feeling I got whenever I walked into comic-book shops. So even though I was interested in comics, I didn’t read them. The way that I was really introduced to comics was through the newspaper. Back when we had newspapers, I loved the daily comics. The black-and-white and then the color ones on Sundays. I was into silly little things growing up — “Garfield,” especially. “Garfield” was my favorite. I was really, really into “Garfield.” Honestly, I can recite facts. I know the day Garfield was born. It was June 19, which is my daughter’s birthday. I know the very first comic, I know all the iterations of Garfield. I can draw Garfield because I was obsessed.

Wow. What was it about “Garfield”?

It was the drawing style, oddly enough. There’s something about the broad black lines. There’s something about that that was very satisfying to my eye so I was very attracted to those type of comics where it was that style. Very clear. And then, of course, Garfield was very moody. And it was an animal. I liked seeing the thoughts of creatures.

How did you eventually get exposed to more serious comics material?

Again, this is in a strange way. I discovered graphic novels during my second master’s degree in literature. It wasn’t because of anything that I was doing in class. I was at the University of Illinois at Chicago and I would go to the library and I was looking for other books I was going to use for research papers and I came across a whole wall of these books. And a lot of them didn’t have covers because they were university copies, so they take the covers off. So I would open them up and I was like, Oh my god, these are comics. And I just started reading them. That was how I discovered them. I discovered Persepolis. I discovered The Rabbi’s Cat. [Will Eisner’s] A Contract With God was the first one, and that remains my favorite graphic novel. I’m obsessed with that one. That was one of the inspirations of LaGuardia.

How did A Contract With God influence LaGuardia? They seem so wildly different.

Yeah, A Contract With God is about Jewish immigrants who come to New York and this tenement that passes on through these generations through these stories. It wasn’t like it was a political diatribe like, Okay, we’re trying to say something. It was more that [author Will Eisner] was telling these stories. He was telling stories from his own background and the stories around him and he was weaving them into this narrative that was very much about people who came from somewhere else and how they rooted in the United States. And also the style, the storytelling style of it, the way that he portrays emotion

How did you end up writing comics? What was the journey that led to you getting these gigs?

Well, the first comic that I did was called ‚ÄúThe Elgort,‚Äù based on one of my characters from my first novel, Zahra the Windseeker. It was for an anthology for DC Vertigo‚Äôs Mystery in Space. That was in 2012. The way that that happened was Joe Hughes, I believe he was an editor there at the time, reached out to me. He was like, ‚ÄúYou seem like someone who would thrive in this medium.‚Äù He marked me early on and said this: ‚ÄúYou look like somebody who would survive in this medium, this seems like something that would come naturally to you.‚Äù It was a no-brainer to me. I was like, ‚ÄúOh, yeah, definitely.‚Äù He was coming to me with a small project. I like to start small. I don‚Äôt like to jump in the deep end before I know how to swim. Then with Marvel, they came to me. They were like, ‚ÄúWe think you‚Äôd be good at this, what are you interested in?‚Äù¬ÝSo that conversation has led to the things I‚Äôve done so far. And then LaGuardia is the same thing. Karen reached out to me and I already had an idea because I had already been incubating the story of LaGuardia. That has always been a comic, always. I‚Äôve been working on that for years. I had worked with Sophie Campbell on an early short of it and I even have the illustrations from that. So when [editor] Karen [Berger] came to me and was like, ‚ÄúHey, would you be interested in doing something for Dark Horse?‚Äù I already had an idea.

What was the earliest kernel of LaGuardia to arrive in your mind?

I think there are two. The biggest one is this idea that I’ve been kicking around in all my stories: This idea of a near future where human beings aren’t the only sentient people on earth. And I can’t tell you why. I can’t. I can’t tell you why I’m obsessed with it, but I am. It makes us have to reorganize everything about the way that we view ourselves and the way that we view others. It messes up so many paradigms. I think that’s a big one. But with LaGuardia in particular, it was the airport.

Literally the airport? As in, LaGuardia Airport?

It was literally the airport. I just had multiple incidents there where I felt very alien. And it stuck with me. It’s usually characters that come to me, but also energy, like rage. Strong energy. It could be incredible joy, but it can also be — and more often is — incredible rage that inspires stories. I felt rage many times in the LaGuardia airport. In a row. I travel a lot and there was a time where I came through that airport multiple times and a similar incident kept happening, especially with my hair, that was really frustrating. Immigration is a big issue in my family and being the child of immigrants.

Is it weird to envision the future at a time in human history when, due to climate change, it seems like we have no future?

I think that not everything needs to be a dystopia. Dystopias are necessary. I’ve written them. But I think that we also need to see optimism as well. Imagination is key to imagining the possibilities and the solutions. We’ve got climate change, right? That is … I don’t want to say inevitable, but I want to say it’s inevitable. It’s coming. These things exist and they’re terrifying. So we need to find solutions for humanity. And being all gloom-and-doom is not going to help us figure out what the possible solutions are. In LaGuardia, climate change still exists but — and I don’t really deal with this much in the book — climate change has been addressed in LaGuardia by aliens. These immigrants come to Earth, and they come with their own knowledge. There were aliens that came and dealt with what’s happening in the ocean. They created things in the ocean that consumed the … you know the garbage islands of plastic? They had things that consumed those. But back to your point, I think it’s important to tell optimistic stories as well as cautionary stories, for the sake of trying to figure out what to do.

Moving to your Marvel work: What do you make of the concept of Wakanda?

Wakanda was the reason why I agreed to even write Black Panther and then Shuri. I’m very interested in Wakanda. When Marvel asked if I wanted to write T’Challa, I hesitated, and it was because of my issues with Wakanda. I had serious issues with Wakanda. And also a lot of my comics friends were like, “You need to do this.” I was like, “Well, okay, if I have these issues with Wakanda, I can address these issues by writing it. I can expand things.” I think it was Stan Lee who created it.

Stan Lee and Jack Kirby together, yeah.

How they created it and their limited ideas and understanding and knowledge of Africa, that’s really what it is. And it’s no judgment on them, but that’s really where I think its issue came from. Because having a country that is the most technological and wealthiest nation in the continent, and then have it hide itself and keep all of its technology to itself from the rest the continent of Africa, with everything around them. They’re landlocked, so that means all the countries around it were having different types of issues, and Wakanda just kinda stayed quiet with all of its technology and wealth. The excuse is, Well, if we let people know, they’ll consume us. I get that, but it’s still problematic. So it’s somewhat unrealistic. Wherever you are, you can’t build a castle in a ghetto, even though I’m not calling Africa a ghetto. But I’m just using that metaphor. And then there’s the fact that vibranium is out and used by other superheroes. Even Captain America, his shield is vibranium. Captain America gets some vibranium but no other part of Africa gets vibranium? Wakanda keeps to itself but takes lots from the rest of Africa, if you look at the cultures. I address that in Shuri, at one point. They speak Hausa, which is a West African language. So they take from the rest of Africa but they keep what they have their resources for themselves. This is really problematic! But with various writers writing it, we each have a chance to build on that and expand on that and correct some of those issues, and that was one of the reasons why I agreed.

With the first thing that I wrote for Marvel, Long Live the King, where I wrote T’Challa’s story, I had parts of Wakanda that cast themselves off of the system. Like, off the grid. It wasn’t that they hated the realm, it wasn’t that they were trying to rebel against the realm or go to war with the realm. They just wanted to be who they were. So, in this narrative, I had it where there’s a plot that happens there and T’Challa has to go in there, and the only way to go in there is on foot. So, T’Challa has to kind of become one of the people and we get to see the people. That was another criticism I had with the storytelling, that its always about the royalty, always about the top of the chain. When you have this type of government structure, there’s a hierarchy. And the stories always kind of focused on the top of that hierarchy. So, with Long Live the King, you just see Wakandans who are just living their lives. T’Challa has to interact with them just as a person, not as a king. That was important to me to portray that kind of moment in the narrative. It expanded just the idea of the people of Wakanda. It wasn’t just like, Okay, we have window dressing and then we have the royals, and that’s all we care about. And with Shuri, there’s something that I’m doing with Shuri that’s very intentional. You’ll see it. It’s quiet.

Any final thoughts about LaGuardia that you want to mention?

First, yes, [the protagonist] looks like me. Yes, okay, fine. Let’s get that out of the way. She looks like me and she’s basically based on me. [Artist] Tana Ford is incredible. I worked with Tana Ford on some of the Marvel stuff and she’s an incredible illustrator. And in some of her illustrations of Future, the main character, she just used some of my pictures. That was, I guess you could say, intentional. The story started with an incident that I dealt with in LaGuardia Airport, so it started with me, so that’s why Future looks like me. So, there. Get that established. People keep saying that to me: “She looks like you, she looks like you.” Yeah, she looks like me. One thing about LaGuardia: it’s not a comic to read quickly. It’s not a comic to just think, Oh, this is like Men in Black. If you think of it like that and you read it with those lenses, you’re gonna miss everything. The way I wrote this, there’s detail in every single panel. Every single panel, there’s story happening. It’s meant to be read slowly, it’s meant to be savored. Look at what’s happening in the background. I guess you would call it a dense comic. I like dense. Because that’s how life happens. There’s a lot more going on. I would encourage readers to Google and research the Biafran War, because there’s a whole aspect about the Biafran Civil War that happens in LaGuardia that I think a lot of readers will miss because they’re completely unfamiliar with that, and I’m not one to explain everything. I like to drop a reader in the middle of it.