The Good Place is not typically described as a political show. But as a comedy that explores the intricacies of ethical behavior at a time when ethical, considerate behavior is woefully absent in many of our political leaders and our conversations about current events, The Good Place has captured the underlying tensions of the current political moment more effectively than most shows blatantly making the attempt.

In this week’s episode, “The Book of Dougs,” The Good Place does that perhaps more overtly that it ever has, and not just because it includes the brilliant line uttered by Jason (Manny Jacinto) when he realizes he and his friends won’t immediately be accepted into the Good Place: “We’re refugees. What kind of messed-up place would turn away refugees?”

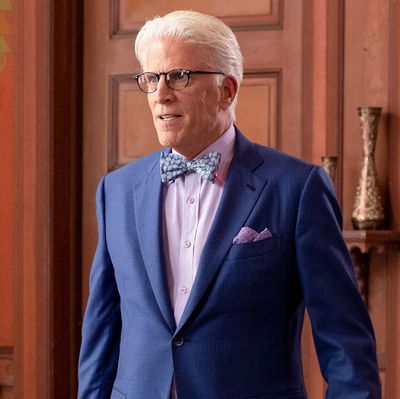

The episode starts making its political point when Michael (Ted Danson), having arrived in the Good Place correspondence center with his fellow dimension-hoppers, decides to file an important grievance about the way the Good Place’s point system works. As soon as Michael takes steps to change that system, he isn’t stopped by people from the Bad Place who are against what he’s trying to do; instead, he is met with resistance from people who understand his concerns, but are so interested in doing the proper thing that they wind up doing nothing. That’s how this episode of The Good Place creates the strongest metaphor yet for what it feels like to be a progressive Democrat living in Trump’s America, while demonstrating how well-intentioned liberal attitudes also can stymie progress.

After Michael, posing as an accountant, manages to set up a meeting with “The Committee,” he explains that the demons from the Bad Place have tampered with the evaluation process that determines who gets into the Good Place, preventing anyone from reaping the rewards of exhibiting kindness for more than 500 years. If you will, they gerrymandered the election process. Or to put it another way, they rigged the system against average, moral people, which pretty well describes how most liberal Americans feel about their government. The six committee members immediately vow to do something about this, which gives Michael hope.

At no point in the episode, written by Kate Gersten, are we given a sense of what the committee’s partisan leanings might be. But it seems fair to assume they lean left. For starters, they’re all dressed like they shopped at L.L. Bean while on their way to an NPR convention: Everyone is wearing button-down shirts, jeans, and fleece jackets. The committee is a model of inclusiveness, with members that represent various ethnic backgrounds and a makeup that achieves perfect 50/50 gender parity. (Actually, the same can be said about the six main characters who just landed in this Good Place–adjacent space.) When they start to discuss what steps to tackle first, one of the officials’ top priorities is to obtain as many pluots as possible from the farmers’ market. (I’d ask why there’s a farmers’ market in the Good Place, but this makes total sense. Heaven is filled with tons of farmers markets, and black raspberries are in season there all the time.) It doesn’t seem like a stretch to assume these are blue-state types who, in a more Earthly realm, would donate annually to EMILY’s List, PBS, and the World Wildlife Fund.

The members of the committee are decent. But, as fired-up-and-ready-to-go progressives and Democrats have often learned, Michael soon realizes they have no capacity to infuse their decency with urgency.

After some deliberation and research (and, presumably, pluot consumption), the committee excitedly tells Michael that they’re going to form an elite investigative team to, first, investigate themselves to make sure they have no conflicts of interest, then to actually suss out whether Michael is correct about the point system being a useless trash heap. Chuck, played by Paul Scheer, happily notes that they are fast-tracking this process … which means that simply forming the committee will take upward of 400 years.

“We have rules, procedures,” says Meg (Tatiana Carr), one of the committee’s members. “We can’t just do stuff.” In other words, when everyone else goes low, the Good Place Committee goes high. And it takes freakin’ forever.

Michael is infuriated by this. “Just so you know,” he reminds them, “the whole time you’re doing this, the bad guys are continuing to torture everyone who ends up in the bad place. Which is everyone!”

“And that deeply concerns us,” Andie (Denise Sanchez), another committee member notes. “Have you seen the memorandum we wrote about how concerned we are?”

It’s possible that Gersten and the other Good Place writers crafted this scenario to illustrate, more broadly, that inflexibility and inertia can be more problematic than following protocol. But it’s hard to imagine that they weren’t also thinking about our current political climate, one in which the Democrats have long been criticized, even before Trump took office, for discussing semantics and in-fighting while Rome burns. Michael’s experience can be read as a critique of Democrats, but also, coming just as the 2020 presidential candidates are beginning to reveal themselves, as a cautionary note. That note says, “All of you who are on the same basic side in terms of values and principles can keep arguing about Bernie Sanders vs. Hillary Clinton, or debating whether Beto O’Rourke is more likable than Elizabeth Warren. But if you do that, the bad guys are going to continue torturing everyone who ends up in the Bad Place. Which is everyone. And also, the Bad Place in this analogy is America.”

This is a great example of something The Good Place does routinely, and what makes it one of the most important shows of this decade: It makes political points that are smart and powerful because they’re not being made in blatantly political terms. I took more away from this one scene of The Good Place than I would have from multiple episodes of Our Cartoon President and a whole season of Saturday Night Live cold opens.

But it’s not the only scene that works on this level. Later, Michael realizes that perhaps all of the problems of the point system can’t be blamed so squarely on Bad Place cheaters. By looking at the point totals for a number of Dougs, aside from the allegedly perfect Doug Forcett (Michael McKean), he realizes that the world has evolved in a way that makes the point system profoundly unfair.

Using Doug Ewing of Scaggsville, Maryland, (shout-out to Howard County!) as an example, he notes that one kind gesture — Doug’s decision to send his mother flowers — resulted in negative point totals because he ordered the flowers on a cell phone that was made in a sweatshop, and chose flowers treated with a toxic pesticide as well as picked by exploited workers, and engaged the services of a company overseen by a racist, sexual harasser.

“Each day, the world gets more complicated and being a good person gets a little harder,” Michael says, summing up another fact of life that confounds any leftie who’s ever craved a sandwich from the famously conservative Chick-fil-A, then suppressed their appetite by imagining how hard it would be to swallow the liberal guilt that would accompany that delicious breaded chicken. Raising this issue allows The Good Place to have another, gentler laugh at the expense of do-gooder progressives who think so darn hard about doing the right thing. But it also raises another serious philosophical question that many Americans grapple with every day: How can you be alive, seek to do no harm, and actually, genuinely, do no harm?

That’s a quandary that’s relevant not just to politics, but to basic human existence. While I’ve always been curious to see where The Good Place is headed next, I’m personally desperate for it to address this in the upcoming last two episodes of its third season. Government can’t solve all our problems, especially not when much of it is still shut down. So what the hell? Let’s find out if The Good Place can.