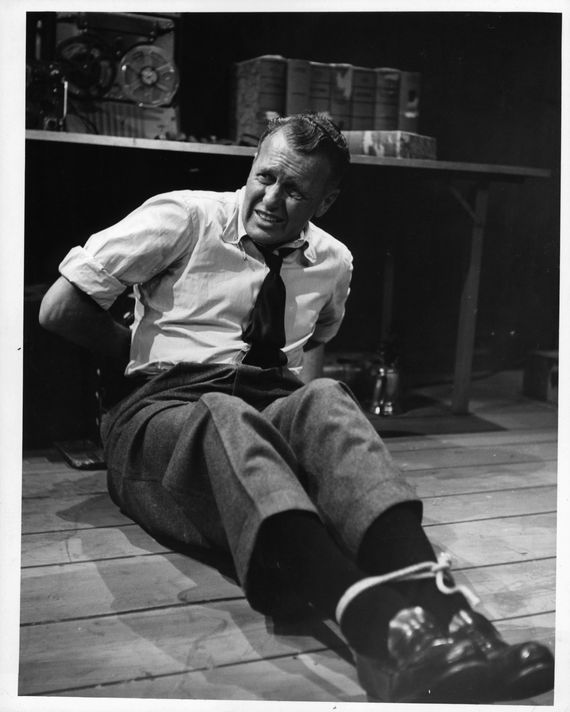

In 1949, CBS started broadcasting a show called Man Against Crime. It starred Ralph Bellamy, and the general idea would be familiar to anybody watching TV in 2019: A crime happens, and then a man “solves” it. Bellamy played Detective Mike Barnett, a beefy, gun-wielding tough who would discover clues and pressure witnesses, rooting out the ne’er-do-wells to return things to the status quo.

What’s striking today about Man Against Crime is not just its fantastically simplistic title, or Bellamy’s hard-boiled, shoulders-and-jawline-centric performance. It’s that in 1949, only the third year TV shows were aired in the United States, television was already keyed into the themes and stories that would dominate the medium for the next 70 years: cops and murderers, mobsters and FBI agents, thieves and fraudsters and violence. Over and over on TV, we watch someone commit a fundamental act of social transgression, ideally one that’s an unusual act of thrilling violence, and then we watch someone else pick up the pieces.

Why is TV overwhelmed with detectives and murderers? What is it about crime that’s made it a quintessential TV story from the very beginning?

Crime is not just a television thing, of course: Books and movies and video games are likewise obsessed. But it’s most noticeable on TV, where on any given weeknight you can turn on network television and have your pick from several crime procedurals, and then flip over to a premium cable channel and have your choice of more high-minded murdery offerings: criminals on motorcycles, true crime, prestige murder dramas, supernatural detectives, detectives working a case across multiple timelines, and so on.

Nor is it a new television thing. Man Against Crime was one of dozens of crime shows in the first decade of TV, including Dragnet and The Defenders, but also lesser known titles like Adventures of Ellery Queen, Mark Saber, Crime Syndicated, and Rocky King, Inside Detective. When ABC finally connected New York and Chicago via coaxial cables in 1949, the first show they broadcast was called Stand by for Crime, a TV adaptation of a radio drama that played the story up to the moment the criminal’s identity was revealed. At that point, the show would pause and invite viewers to call in with their guesses. In the earliest years of TV, crime didn’t yet make up such an overwhelming percentage of TV programming — although the numbers are higher if you include the Westerns, many of which followed the same central good-guy-with-a-gun formula — but there were enough to suggest that crime has been a part of TV’s DNA from the very beginning.

There is an easy answer to why that might be: We like crime stories because they’re full of all the things we’re not allowed to do, all the dark corners of the human imagination we know we shouldn’t indulge, all the scariest, most alluring, most sensational kinds of behavior we could never do because it’d blow up our regular lives, but which would make things so much more exciting if we did. They let us play out hypotheticals. What if I murdered my boss? What if I robbed a bank? What if I were allowed to roam the streets with a gun, kicking down doors and arresting whoever I felt like with no impunity? Crime TV can be dark and gritty or silly and escapist, or voyeuristic or drily distant, but it’s always about disrupting the everyday. Breakfast is boring, and you already know what breakfast looks like. Murder is not boring, and TV can show you something you haven’t seen in your own life.

There’s a whole subgenre of TV that circles around this idea: Crimes are exceptional, criminals are mysterious and bizarre, and we want access to the titillating, horrible things we cannot see in regular life. Bones found more grotesque, unimaginable ways to dispose of a body than I could’ve ever dreamed possible. Shows about serial killers like Mindhunter, True Detective, or The Fall present their murderers as edge cases of humanity, uncanny broken evil things we want to stare at because they scare us. The voyeurism angle is even more obvious in true crime, where, for instance, The Jinx focuses a camera on Robert Durst’s glassy-eyed twitchiness for hours on end so we can marvel at his monstrousness. We like crime shows because they’re about scary dark things, and we can watch them and get an adrenaline hit.

There’s also another kind of crime TV show, one that often gets called “cozy” or “escapist,” that’s less about reveling in the human capacity for evil, and is more about images of safety. There’s a hefty British tradition of these (Foyle’s War, Midsomer Murders, Shetland, Lewis, Father Brown, all the Agatha Christie adaptations), and plenty of Canadian and Australian entries (Miss Fisher’s Murder Mysteries, Murdoch Mysteries), but there’s a solid American cohort as well. Murder She Wrote, Matlock, Columbo, more recent shows like Psych, Monk, Castle, or Elementary — no one’s watching them for soul-rattling dives into the human psyche, or for hypotheticals about what it would take to drive someone to murder. They are about reliable patterns of tension and release, about breaking the status quo and then fixing it, every single week.

Most crime stories, especially the giant body of TV police procedurals, also constantly reinforce a particular idea about who gets to be the default viewer. By positioning crime as enjoyable, as a vacation from the everyday, crime stories emphasize whose experience gets to be the “everyday.” If you live your life aware that, without warning, you could get pulled over for a broken taillight and then imprisoned for resisting arrest, and potentially shot and killed in the process, your relationship with policing and crime is not reflected by a CBS procedural’s fun pursuit of dastardly bad guys. When we call crime stories “escapist,” the implication is that they are vacations you can return from. They’re jaunts into deviant behavior that promise the usual order will reassert itself, and that institutions like the police, the FBI, the courts, and superheroic private eyes will stop the evildoers eventually. The shows that don’t work this way, especially mob shows and other crime stories that make the criminal the protagonist, tend to valorize a very specific kind of criminality that is its own version of social reinforcement: Criminal protagonists are often white men, whose crime helps support some kind of “family,” and who are usually put in opposition to a police system that’s corrupt, making their own crimes somehow more acceptable.

That’s one answer for why there are so many crime stories on TV: They let us imagine an alternate existence where we could smash the current social order and run berserk through the streets. But at the same time, these crime shows quietly reinforce the idea that getting in trouble with cops means you’re bad, the status quo is (mostly) good, and the occasional white male criminal mastermind who evades the law is probably meting out his own rougher but still meaningful form of justice.

The other answer is simpler: We like crime stories because crime stories are questions. Who did it? Why did they do it? How did they do it? Will they get caught? Even the messiest, most complicated, most gorgeously complex stories about criminals still imply answers. They imply endings. That makes crime perfect for TV, a medium that’s lived for decades on the need to negotiate between one ending (the end of an episode) and another ending hovering somewhere far off in the distance (the end of a series). It’s ideal for serialization, too: horror, but contained. For stories where that containment doesn’t happen on the level of the episode, in shows like The Shield or True Detective, the mechanism for containment is nevertheless ready to deploy whenever you need it. Ending the story is just a matter of letting the handcuffs snap shut, or revealing the solution to the puzzle, or letting the criminal drive off into the sunset, or killing someone. Telling stories with predictable ends is comforting. Telling stories that flout those predictable ends is even better.

If Man Against Crime is the title that best represents the genre, the other 1949 series Stand by for Crime is the title that best explains the genre’s appeal. Crime is a dangerous, unexpected, status quo–disrupting event, something performed by inexplicable, inhuman people, something that must be solved or fixed or at the very least investigated. On TV, that experience is controllable. If you stand by and wait, a crime will appear at a predictable time. It will come prepackaged with a solution, or, if not exactly that, its terror will be mediated by being a story told to you, rather than a crime happening to you. Turning crime on and off feels powerful and soothing. It is a way to see the darkest parts of humanity while also being assured of your own safety. Because when you watch crime on TV, you’re not out there being murdered or robbed or violated by some terrifying, unknowable evil. You’re at home, on your sofa, sitting in front of your television.

More From This Series

- A Very Simple Guide to True Detective’s Multiple Timelines

- True Detecting True Detective: Let’s Lay Odds on Who the Killer Is

- Extremely Wicked Director on How Ted Bundy ‘Seduced’ His Victims

- The Ocean’s Effect: How the 2001 Film Changed the Heist Movie For a Generation

- Why Isn’t Law & Order Streaming Anywhere?