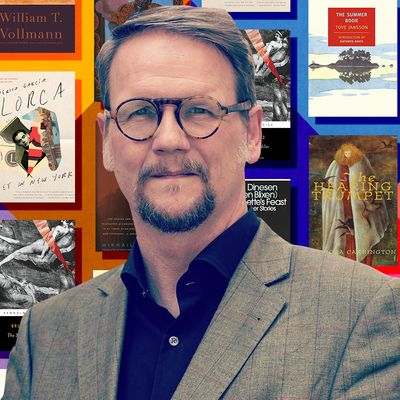

Bookseller One Grand Books has asked celebrities to name the ten titles they’d take to a desert island, and they’ve shared the results with Vulture. Below is Icelandic novelist and poet Sjón’s list.

A novel that has as its main character an Old Lady who is liberated from the boredom of her secure life at an eccentric home for elderly ladies when given a hearing trumpet — and whose wish to go to the North Pole before she dies comes true in the most unlikely fashion — has to be good. Even though she is better known as one of the best painters of Surrealism, Leonora Carrington’s novels and short stories have had a strong influence on feminist and fantastic fiction. Constantly entertaining and unpredictable The Hearing Trumpet is infused with warmth and rebellion in equal measures.

Set in Reykjavík at the turn of the 20th century, this novel has a Chaplin-esque quality in its celebration of how the good values of society are to be found among those clinging to its lowest rung. Álfgrímur is an orphan living with an old couple who have opened their small farm to the misfits and the meek. A nearby graveyard becomes the boy’s playground, and it is there he is discovered to have “the pure tone” while singing at funerals of the lost and lonesome. From their gravesides he goes into the world to become a singer. It is my favorite book by Laxness, not least because it is his attempt to understand why someone like himself, born in a town of 10,000 people, found the right melody to transform the stories of a small world into world literature.

Bruno Schulz’s slim output of stories were all he needed to publish in his lifetime to earn his place alongside other 20th-century giants like Franz Kafka and Jorge Luis Borges. Not that he didn’t hope to write and publish more. A Galician Jew, his life was cut short when he was shot dead in the streets of Drohobych in a tit-for-tat between German officers of the occupying Nazi force. What survives is the people and other beings of the ghetto Schulz made eternal and universal in a text where everything has the right to respect, even a tailor’s dummy.

If what makes a work of literature a classic is its ability to be a mirror held up against all times and all human societies — the personal experience and the political one — I think this short novel by Isak Dinesen (or Karen Blixen in her homeland, Denmark) must be in the process of becoming one. Read against our own times it can be seen as a simple tale about a woman on the run from civil war who seeks refuge in an isolated community. Bringing nothing along with her into her exile but her natural kind spirit and knowledge of the culture of the culinary arts, Babette makes a quiet existence for herself as a simple housekeeper until the day she gets the opportunity to show and share her extraordinary skills. And there is nothing simple about that.

In my teens I got to know García Lorca’s poems in Icelandic translations. I was instantly fascinated by their dramatic tales of tragic loves, their intense night visions and images of human and botanic flowers. Infused with a surrealist use of metaphor, folkloric energy derived from flamenco, and the Arabic heritage of al-Andalus, Lorca’s poems reach deep into the ancient origin of soul while flashing with modern wit and bravery. Wonders happen when the poet travels over the Atlantic and tests his poetic tools in America.

This slim novel is one of the most intriguing works of literature I have come upon in a long while. Part mystery, part metaphysical journey, part fairy tale, part adult love story, it brought me to a state of the most welcome strangeness, similar to the one I sought out as a young reader of books that challenged how we perceive reality and reconstruct it in text. In the narrative’s mysterious, slow burn of a chase, a woman who has left her husband is tracked down in the Taiga, a territory where the laws of nature are as much out of joint as the rules of its isolated human society. In its uneasy atmosphere there are echoes from Tarkovsky’s film Stalker, as well as from golden-age private-eye novels.

I don’t hesitate to state that no one becomes a great writer without drinking from the spring of fables. Sometimes their influence shows on the surface, and at other times it remains hidden inside the story like bones in a body. In this magnificent collection of dark stories, Vollmann — who many consider having written the Great American Novel more than once — proves himself a master storyteller whose pitcher of that fabled water never runs dry. Drawing on sources from the north, the south, the east, and the west, he takes us on a journey through many last nights on earth and in the worlds beyond.

Throughout my writing life I have relied on Marina Warner to guide me through the hidden realms of literature and culture. She has a vast knowledge of folk stories, religious tracts, legends, and classical works from all points of the globe, and her analysis of how they continue to be present in our lives and work is always inspiring. In Stranger Magic, she tells the story of how Scheherazade’s tales in the “Arabian Nights” were embraced and appropriated by Western culture without ever losing their original power. As I am working my way toward a new novel, which includes the influence of Arabic culture on medieval Icelandic writing, Warner has once again provided me with her keen insight into the mechanisms of how stories travel.

I read it first as an 18-year-old and, just like a meteor from a distant galaxy, it hit my tender young brain and dug its way deep into its gray material. It has nestled there ever since, radiating with beauty and wonder, irony and horror. This autumn I visited ground zero of The Master and Margarita, the famous Patriarch Ponds in Moscow where Lucifer himself, in the guise of the Professor Woland, makes his first appearance in the book and sets the whole story in motion. For a second I wondered if he would come for me, too. But then I remembered that Old Nick owned my soul already, having given it as a toy to Bulgakov all those years ago.

As counterweight to the weird and eerie elements in many of the books I have selected I propose the sweet and kind Summer Book. Tove Jansson’s fictionalized memoir about the summers she spent as a girl with her grandmother on a tiny island in the archipelago off Finland’s south coast is a wonderful ode to the curiosity of childhood and the wisdom of old age. In a precise, lyrical language that never gives in to easy sentiments, Jansson allows us to take part in the summer days with the girl and the grandmother as one is discovering nature for the first time and the other is contemplating its vulnerability. It is sunshine in the shape of a book — for the shadowy part of Jansson’s oeuvre one must look to her children stories about the Moomins.