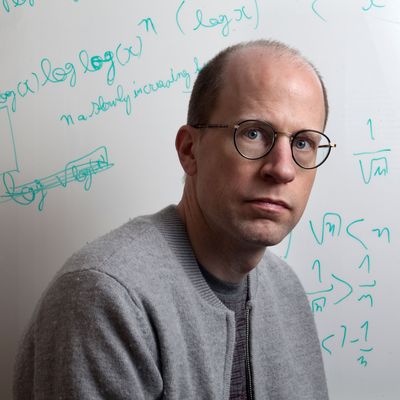

When Morpheus told us our reality was fake, it sounded far-fetched. Since then, though, the idea has picked up steam. In 2001, two years after The Matrix hit theaters, Oxford University philosopher Nick Bostrom circulated the first draft of his “simulation argument,” which posits three scenarios: (1) Humanity will go extinct before creating technology powerful enough to run convincing simulations of reality; (2) humanity will live to see such technology but decide, for whatever reason, not to run any simulations; (3) humanity will create that technology and run many different simulations of its evolutionary history — in which case there would be lots of simulated realities and only one non-simulated one, so maybe it’s more likely than not that we’re living in a simulation right now. That third scenario has excited many over the years, including Elon Musk, who in 2016 put our odds of living in a non-simulated reality at “one in billions.” We called Bostrom to discuss his paper’s legacy.

When you first published this paper back in 2001, had you seen The Matrix?

I don’t think I’d seen it. I had some relevant background that made it possible to come up with the simulation argument. In my doctoral dissertation, I had worked on observation selection theory, which is a kind of methodology that enables one to reason probabilistically about questions having to do with indexical information — like who you are, what time it is, where you’re located. Also, I’d for many years been thinking a lot about the future capabilities that technological progress can be expected to unlock — the future of AI, future of computing, nanotech, and other things like that. So, when you have those two pieces of background, then the simulation argument is really only one step away from there. It occurred to me that you could do something more than just ask the general law — how can you be sure that you’re not dreaming, or that you’re not a brain in a vat, or that you’re not in a computer simulation — and that there was a precise argument that you could formulate. It tries to show that one of three propositions is true, and one of them is the simulation hypothesis. So then I wrote that up, published it, and it has attracted an enormous amount of attention since.

What was the initial reaction like?

It got a lot of attention from the outset, and since then it’s come in waves. I don’t know exactly what causes this phenomenon. Maybe it’s a new set of people that discover it for the first time. But yeah, it’s continued to get a lot of attention ever since.

It’s attracted some prominent followers over the years.

Obviously, in terms of public statements and such, Elon Musk was the most prominent. I think simulation theory had been quietly discussed before that but as an “around some glasses of beer with friends” type of thing.

What was it like to hear Musk talking up your theory?

I’m not sure whether there was anything it was particularly like to hear that. I’m a little surprised that he felt comfortable being so direct and explicit about it. But then, that’s his style compared to a lot of other CEO’s who hold their personal convictions and personal life close to their chest. He is more of a public figure and is happy to say what he thinks about a lot of topics.

Have you spoken to him about the simulation theory?

Not about simulation theory. We’ve talked about other things, AI and such.

There was a 2016 New Yorker profile of Y Combinator’s Sam Altman that said many in Silicon Valley had become obsessed with your simulation hypothesis and that “two tech billionaires have gone so far as to secretly engage scientists to work on breaking us out of the simulation.” What do you think when you hear people are doing things like that?

I suspect that the work is probably not on a very large scale. It’s kind of unwise to try to break out of the hypothetical simulation. The chances of success are negligible. If it doesn’t work, it’s a waste of money, and if it does, it might be a calamity. It at least seems like the kind of thing that you would first want to think about for a while, whether it would be prudent to try to do that before embarking on it.

As a civilization, we’re not very sophisticated in thinking about these kinds of things and what makes sense and doesn’t. It seems to be more at the level of, Oh, here’s a fun idea. I’m gonna have a go at it. You see the same thing with our efforts to contact extraterrestrials, the messaging to extraterrestrial intelligence that some astronomer types have been engaged in, sending out these with the Arecibo and stuff over the past decade. It seemed that the first impulse was to do it, then maybe afterward you think about, Oh, was that actually wise? If there are extraterrestrials, are we sure we want to show them where we are? Like, what’s the cost-benefit analysis? But the action comes first and the thinking about whether it’s wise comes after.

Do you ever hear about scientific breakthroughs — say, a quantum-physics experiment purporting to prove that our reality is not a simulation — and consider them in relation to your hypothesis?

No, nothing with quantum physics. But the advances toward ever-faster computers have slightly reduced the probability that civilizations at our stage will go extinct before reaching technological maturity. The closer we get to technological maturity without having gone extinct, the less probable that one seems. But that’s more an incremental change. I mean, we’re not that much more advanced than we were in the early 2000s, but a little bit more.

At the meta level, I haven’t really seen any convincing objections or attempts at refutation [of the simulation hypothesis]. So the absence of that also, I guess, strengthens my confidence that the reasoning is sound.

Have you seen The Matrix or either of the sequels since you wrote this paper? What did you think of them?

Yeah. I saw … it was such a long time ago. Certainly the first one, and at least one of the others. I remember liking the first one. Compared to most Hollywood movies, it was more interesting and more thought-provoking than the average blockbuster. So if that’s the standard, I think it was cool. Also, the style — they had these black trench coats and the bullet time, and there were some kind of cinematic and stylistic elements completely independent of any philosophical significance — that was, I think, a little bit innovative at the time. The sequels were maybe less solid. They made, as I recall, an effort to try to make it profound by inserting references from different religions and different philosophical systems. Just kind of a little bit like in the corvid family [of birds]. They pick up these shiny objects from the worlds of theology and spirituality and philosophy and just drop them into the movie, but without it necessarily making sense or being coherent.

Are you familiar with the “glitch in the matrix” meme?

No.

It’s this internet meme where people will spot things out in the wild, like three unrelated people wearing the same outfit, so they look like identical video-game NPCs. It seizes on this idea of reality as a repetitive computer program.

I haven’t come across that as a meme. But now that you’ve mentioned it I’ll keep my eyes open for it.

Are you familiar with the “Mandela Effect”?

No. Maybe I just forget the name of it. Maybe I’ll recognize it if you describe it.

It’s a term for a sort of collective misremembrance of something. A lot of people seem to remember Nelson Mandela dying in the 1980s, even though he lived until 2013. Supposedly, it’s proof that whoever’s in charge of our simulation is changing the past.

I don’t think it’s related at all, actually. I think if we assume that we are not in a simulation, you would still expect there to be various reports of anomalies, paranormal phenomena. Some people have delusions, some people misremember something, sometimes there is a collective phenomenon where a lot of people are mistaken together. I think just from human nature and from reporting bias you would expect to hear those things every once in a while.

Has any strange or unexpected news in the world — Trump’s election or Brexit — made you think we’re more likely to be living in a malfunctioning simulation?

I hear [about these events] sometimes. Sometimes, an individual will write to me and say they had some personal experience that they attribute to being in a simulation. So, maybe with psychological problems. At any given time, there are metaphors that people reach for if they experience something and don’t know how to fit it within a normal framework. In earlier ages, they would say they were possessed by a demon. And maybe there are other metaphors to reach for that I’ve heard about that are in the Zeitgeist with computers and their simulations or whatnot.

I don’t think [unusual news] is evidence of a simulation. We’re fairly ignorant about what kind of simulations would be produced. So we can only make weak inferences from those kinds of observations. If you had some view about what kinds of simulations would be more likely to be created or created in larger numbers, then in principle, you could see when the world seems to take the shape of one of those. That might be some evidence in favor of the simulation hypothesis.

Do you play video games? I’m thinking of detailed open-world games like Grand Theft Auto or Red Dead Redemption.

Not a lot. I have a son now who’s just reaching the age where he can play computer games. So I play a little bit with him. I’ve seen footage. I haven’t played them, but I know of them. I think that helps make it easier for people to take seriously something like the simulation hypothesis, that you can get these quite immersive three-dimensional virtual-reality experiences even with present-day technology. It doesn’t take a huge leap of inference to think that could get better and eventually maybe good enough that you can’t tell the difference. So it makes it less simply an abstract claim, with some probability theory and some formulas, and more something that people can experience themselves. That brings it home on a more gut level that simulations are a real possibility. You could see a very advanced civilization maybe being able to create high-fidelity simulations and a lot of them.

Thinking about Moore’s law, and examining the upward curve of technological progress, how far do you think we are from being able to produce a simulation that’s indistinguishable from our own reality?

I think basically, it’s post-superintelligence. That is, we’ll first develop machine superintelligence, and then that will maybe quite rapidly bring us to something approximating technological maturity. At which point, a whole big space of things become feasible, including realistic simulations and other sci-fi-like technological possibilities — space colonization and so forth. So the question then, from my point of view, kind of reduces to, How far away are we from machine superintelligence? Of course, there is uncertainty over that. But I don’t think it would take a thousand years, assuming civilization doesn’t destroy itself some other way. It seems quite possible that in this century we will crack the problem of producing general intelligence in the machine substrate. So then some of these even seemingly more radical technologies might follow fairly swiftly.

Your paper presents three possibilities for the future of human civilization. In the years since you published your argument, has the likelihood of any of these possible futures shifted in your mind? Which is the most likely?

Yeah, it’s shifted somewhat. Now you’re going to follow up and ask which. I’ve tended to punt on that question a little bit. I tend to refrain from being all that precise for various reasons. One is, if I gave some specific probability of what I happen to think, then that number could come to seem as if it were more scientific or more precise than our state of evidence actually warrants. It becomes very easily quotable. Like, “That Oxford professor says there is X percent probability that you’re living in a simulation!” I’ve tried to focus more on the underlying reasoning, the argument structure that leads to this conclusion, because, yeah, the original simulation argument itself doesn’t on its own distinguish between these three possibilities. It just says at least one. So if you want to go further, you have to add additional considerations.

If you don’t want to give a numerical probability, would you at least be willing to rank them in terms of likelihood? What’s most likely or least likely?

Yeah, I think maybe not at this stage. I have had further thoughts on the topic. I mean, aside from the probabilities, like just in terms of the implications and so forth. So far I haven’t really published anything more since that original paper, except for some minor pieces that defended the initial argument against objections that I thought had failed. Then there was some little clarification on some points. But I’m continuing to think about how — if one thinks of the simulation argument as imposing this constraint on what one can coherently believe about the future and our place in the world — how does that connect up to other big-picture questions? One’s thoughts about AI, or about extraterrestrial civilizations or multiverse theories or a bunch of other fairly fundamental parameters to our world view, and our scheme of priorities might depend on what stance one takes on these issues.

I’ve continued to think about that, but not yet published much, because I haven’t figured out yet whether it would be helpful to do or not. I want to try to avoid doing things like trying to “hack out of the Matrix” before you know whether it’s a good idea, or beaming electromagnetic signals to extraterrestrial civilizations before figuring out whether that’s a good idea. Maybe first figure out whether it’s a good idea and then follow on with the action after that.

*A version of this article appears in the February 4, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More From This Series

- The Beatific Imperfection of Keanu Reeves in The Matrix

- How The Matrix Got Made

- The Matrix Taught Superheroes to Fly