This series originally ran in 2019. We are republishing it as The Matrix Resurrections hits theaters and HBO Max.

If you were of moviegoing age in 1999, you may recall The Matrix’s debut, which hardly seemed to herald a movie we’d be talking about 20 years later, let alone praising as singularly important. The film opened on March 31, not traditionally a release date reserved for potential blockbusters. (Also released that day: 10 Things I Hate About You.) It starred 34-year-old Keanu Reeves, an actor of wavering fortunes whose career, at times, had served as a punch line. Having emerged in 1986, in River’s Edge, Reeves was introduced to the wider world in 1989’s Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure, then rechristened as an action hero in 1994’s Speed — only to run aground again with films like A Walk in the Clouds and The Devil’s Advocate.

His role as Neo — which eventually earned him over $250 million, thanks to his stake in the franchise — had been turned down by Will Smith, Brad Pitt, Nicolas Cage, and Val Kilmer, among others, and dangled briefly to Johnny Depp. As for the film’s creators, the Wachowski siblings, they were best known for 1996’s Bound, a small but well-received neo-noir, itself best known for an extended sex scene between Jennifer Tilly and Gina Gershon. The Wachowskis, both college dropouts, had started out in the world of comic books and were avowed fans of horror films and Japanese anime. They sold a screenplay titled Assassins to Warner Bros. in 1994, and the deal included two other potential projects: Bound and The Matrix. They’d originally envisioned The Matrix as a comic book, and the script was, they later said, a “synthesis of ideas that sort of came together at a moment when we were interested in a lot of things: making mythology relevant in a modern context, relating quantum physics to Zen Buddhism, investigating your own life.”

Assassins, by the way, surfaced in 1995 as a heavily rewritten film starring Sylvester Stallone and directed by Richard Donner; the Wachowskis disavowed it. The involvement of Stallone (America’s favorite action star of yesteryear) and Donner (the director, in 1978, of the first successful modern superhero film, Superman) later took on an ironic resonance, as The Matrix would both end the era of action movies that Stallone represented and reinvent superhero films to make them integral to the culture going forward.

But back to 1999. In short, if you’d walked into The Matrix on a balmy night in March and proclaimed that it would be the single most influential American movie since Star Wars, you would have sounded insane. Even the Wachowskis had their doubts. “We just really want to see how the idea of an intellectual action movie is received by the world,” Lana Wachowski said in an interview at the time. “Because if audiences are sort of interested in movies that are made like McDonald’s hamburgers … then we have to reevaluate our entire career.”

Instead, it was Hollywood that reevaluated everything. And only now, 20 years later — with nearly as much cultural distance between the present moment and The Matrix as between The Matrix and Star Wars — is the revolutionary extent of that reevaluation clear.

Let’s start with the obvious, oft-remarked technical leaps: the film’s wire fighting and ballistic theatrics, imported directly from Hong Kong action films, and “bullet time,” the slo-mo special effect that was so eagerly and instantaneously imitated that it showed up as a sight gag in Scary Movie barely a year later.

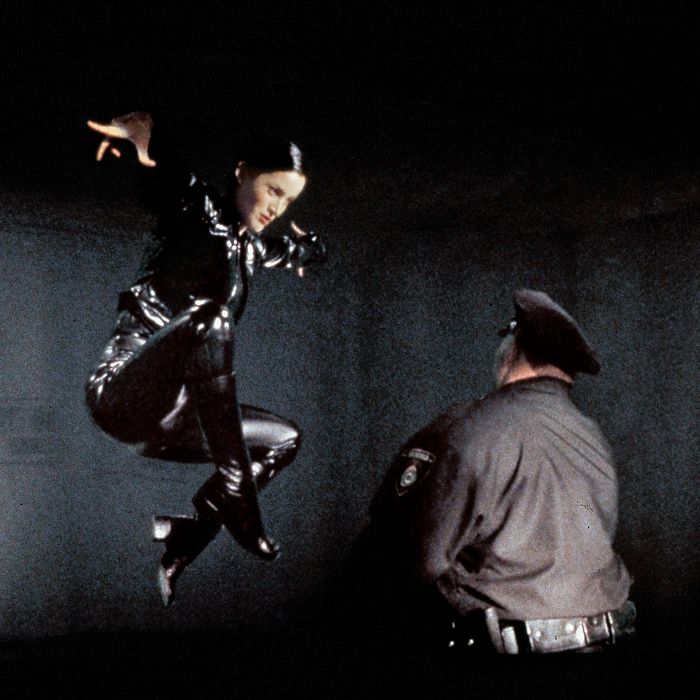

Then there’s the way The Matrix single-handedly revived the American action film, a once-muscular genre that had atrophied into self-parody. Nineties-era films like True Lies, Con Air, and Face/Off offered variations on the same steroids-and-nitroglycerine cocktail audiences had been imbibing since the ’80s. The Matrix, by contrast, featured androgynous whippets who moved like ninjas, spoke in koans, and dressed like S&M dominatrices. Prior to The Matrix, action stars were either hypertrophied musclemen like Stallone and Schwarzenegger or bulked-up refugees from dramatic acting like Travolta and Cage. Thanks to the peculiar physics of The Matrix — and its adherence to the international precedent not of Jean-Claude Van Damme but of Chow Yun-Fat — our idea of action heroes transformed radically.

Muscle tees and macho bravado were out; yoga-toned physiques and contemplative determination were in. As an ass-kicking Neo, Reeves not only opened the door for Angelina Jolie as Lara Croft but kept it open for Matt Damon as Jason Bourne, Uma Thurman as the Bride in Kill Bill, Liam Neeson as that reluctant super-dad in Taken, and, to come full circle, Reeves himself as a mournful, pooch-loving assassin in John Wick.

As a side benefit for action fans, The Matrix also managed to miraculously revive the sort of trademark taglines made famous by Schwarzenegger & Co. — “I’ll be back” and so on — which had been rendered ridiculous by a decade of spot-on satires. (To a certain generation, McBain, on The Simpsons, yelling, “Mendozaaaaaa!” will never not be funny.) When Neo says, in his Keanu Zen tone, that he’ll “need guns, lots of guns” and racks of automatic weaponry appear, or when Trinity levels a gun point-blank at an Agent and says coldly, “Dodge this,” you don’t laugh, you don’t cringe, and the hairs on your arm reliably stand at attention.

It was obvious even in 1999 that The Matrix had reinfused action movies with swagger. Evident only now is how it managed to do something even more monumental: teach Hollywood how to put superheroes on film.

If you don’t think this was a significant development, consider that half of the top-12 highest-grossing films of the past ten years (and six of the top nine non–Star Wars films) have featured costumed crusaders — which is true of zero of the top-20 highest-grossing films of the ’90s. Pre-Matrix, Hollywood had left the superhero genre for dead. There was Donner’s successful Superman, Tim Burton’s successful Batman in 1989, a few diminishing-returns sequels for each, and not much in between.

For Hollywood, the dilemma of the live-action superhero film had always been that it looks inherently ridiculous. (Blade, a modest 1998 hit about a vampire hunter, escaped this trap by being a superhero movie in horror-film drag.) Donner leaned into the cartoonish aesthetic with his gee-whiz, curly-locked Christopher Reeve as Superman, then Burton bulldozed through it with his kitsch-pastiche Batman. (Joel Schumacher later added nipples.) Comic books rely on people in ridiculous outfits routinely bending physics, two elements for which movies had not yet found a convincing visual language. The Matrix provided that language and, what’s more, made it look awesome. The film’s central conceit — that the characters exist within a computer simulation and, once they figure this out, are capable of miraculous feats — allows for a world where lithe weaklings can plausibly pummel muscle-bound goons and where Ted from Bill & Ted can punch Hugo Weaving a hundred feet in the air. This world conditioned us to believe in a fistfight between Tom Hiddleston and the Hulk. The tagline for Superman was “You’ll believe a man can fly”; at the end of The Matrix, over the opening chords of a Rage Against the Machine song, Neo flew. And we believed.

Of course, the post-millennium superhero renaissance also has a lot to do with CGI. Iron Man can soar in ways Superman and Lois Lane only dreamed about. But that’s another trick The Matrix taught Hollywood: CGI isn’t the future; it’s right now. Steven Spielberg’s decision to use computer-generated dinosaurs alongside animated models in 1993’s Jurassic Park proved CGI could be seamlessly incorporated into live action. Six years later, The Matrix went one better, convincing moviegoers that a simulation could be just as thrilling as reality. Its story line and special effects worked in elegant synchronicity, heralding films like Avatar and Ready Player One by proving that an audience can care as much for pixels as they do for real people.

Like all good superhero movies, The Matrix is also inherently ridiculous, but it took itself very seriously and, surprisingly, so did we. Unlike kid-friendly hits such as Independence Day and Men in Black, The Matrix arrived with an R rating. It was intellectually ambitious and outrageously violent, and it tackled the kind of “Whoa, dude!” questions familiar from bong-fueled dorm-room debates. If old-school action films like Stallone’s Cliffhanger dared you to imagine a man hanging from a cliff, The Matrix dared you to reconsider the nature of reality. As it turned out, we liked our mayhem with a side dish of Baudrillard.

Without The Matrix, you likely don’t get the rise of Christopher Nolan. We needed the bridge of Neo to get us from Burton’s cartoonish Batman to a Dark Knight who growls in caves. Nolan’s subsequent hits, like Inception and Interstellar, don’t just engage in Matrix-like philosophical musings, they revel in them. Without The Matrix, we likely miss out on the Lord of the Rings trilogy and, later, Game of Thrones, because The Matrix served as a proof of concept for the notion that mainstream America was willing to lose itself in a sprawling, self-serious fantasia. Without The Matrix, we also don’t witness the metastasis of brainteaser speculative fiction, from Lost to Black Mirror to Westworld — along with the requisite belief among both creators and fans that no narrative is complete without a big-twist reveal.

Ever since The Matrix, everyone’s been chasing the whoa.

Self-serious, special-effects-heavy universes orchestrated by distinctive but little-known auteurs (often packaged in sibling pairs; Wachowskis, meet the Russos) are now the reliable reality for Hollywood. These films and TV shows have become, in effect, the Matrix within which pop culture resides. So it may be hard to remember that The Matrix also appeared at the end of a decade characterized by cultural friction: the clash between a moribund mainstream and an ascendant counterculture. Pop music in the ’90s was Britney Spears but also Nirvana; Hollywood was Forrest Gump but also Miramax. There was a growing sense that the roiling underground was rising up to subsume the status quo. The Matrix provided the exclamation point at the end of that era by proving that these two sensibilities could be cannily combined into a single, successful movie. It rose to merge two competing worlds. Culturally speaking, The Matrix was the One.

The genius of Star Wars was how brazenly it borrowed from Hollywood’s classic conventions: the Western, the war movie, the cliffhanger serial. The Matrix pulled the same trick but, like a magpie in wraparound sunglasses, did it by scavenging the global underground. It stole from manga, anime, and S&M dungeons; from cyberpunk, tech noir, and gun fu. It wrapped a queer coming-out fable in fetish latex, dusted it with gunpowder, released it at the multiplex, and made more money than Runaway Bride. One of the film’s great subversive triumphs is that it features a love story between two captivating characters — Neo and Trinity — who look like slightly gender-queered versions of the same person. It took four more years and two more films before the Wachowskis added “revolutions” to one of their titles, but it was clear in 1999 that The Matrix had defined the revolution and won.

Perhaps the greatest evidence of the film’s outsize influence is how difficult it was to replicate, even for its creators. The original’s impact has been dimmed in hindsight by its sequels, which landed, one right after the other, as dispiriting duds, crushed by their own pomposity. Ironically, the Wachowskis were partly done in by technology, a desire to push what was possible — as in The Matrix Reloaded’s infamous “Burly Brawl” sequence — far beyond what was advisable or thrilling. But maybe the magic of The Matrix was always bound up in that thrill of the whoa. Once your eyes were opened to The Matrix, you couldn’t unsee it or forget it, but you also couldn’t discover it twice. Let alone three times.

The Matrix stands now as a cinematic monument, yes, but also an enduring fable about collective dreaming — which is, of course, a powerful metaphor for the experience of watching a film. That’s ultimately what The Matrix accomplished in a more profound way than any popular film had done since Star Wars: It rewired our desire to dream. We no longer want, or want primarily, to escape, and we are no longer satisfied with buoyant cartoon fantasies or Westerns repurposed for outer space. We want to be converted. We want thrills that will make us think. We want spectacle, but we also want visions.

As the man in the sunglasses with the pills in his palms once promised: Once you choose, you can never go back.

*This article appears in the February 4, 2019, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

More From This Series

- The Beatific Imperfection of Keanu Reeves in The Matrix

- How The Matrix Got Made

- Neo’s Stunt Guy on How The Matrix Changed Action Forever