Over the next few weeks, Vulture will speak to the screenwriters behind 2018’s most acclaimed movies about the scenes they found hardest to crack. Which pivotal sequences underwent the biggest transformations on the way from script to screen? Today, writer-director Bo Burnham — who has been nominated for a Writers Guild of America Award for Best Original Screenplay, a Directors Guild of America Award (First Time Feature Film), and an Independent Spirit Award for best first screenplay — explains his difficulty plotting a key third-act scene in the coming-of-age dramedy Eighth Grade. It’s a climactic exchange in which awkward eighth-grader Kayla (Elsie Fisher) asks her father (Josh Hamilton) for advice. The scene is then excerpted below.

The relationship between Kayla and her dad over the movie is like, “I love you.” “Shut up.” “I love you.” “Shut up.” Mostly her pushing him away and wanting personal space and not wanting her father’s input when he’s trying to get in on her interior struggle. As a kid, you don’t want your parent to double-team your problems for you — to make you feel like even more of a fucking loser than you already are. But at this low point in the movie, she finally asks him the question: “Do I make you sad?”

The first 60 pages of the script were me writing in buckshot manner. I was in a bad place in my life and just wanted to enjoy the writing process; I was tired of writing feeling like homework to me. I was trying to put Kayla in situations I found interesting and compelling. The hope of the movie is to follow her subjective experience, not to ever feel like the plot is pulling her in any direction — the traditional pillars of plot don’t necessarily exist in the average eighth-grader’s life. This is one of the few scenes where I actually felt the real pull of the plot: needing this thing to deliver in a significant way. It was the most difficult to write because it’s the most intensely felt and it is the crux of the film. It sort of feels a little disingenuous when things go like that in writing. Like, “I’ll just try to service the climax of the story rather than the emotion of the story.”

I felt a lot of external pressure. If this film is written correctly, this scene shouldn’t be any less or more important than any other. I should just treat this scene honestly like you need to treat every scene honestly. It’s a problem if, all of a sudden I pop out of what I’m doing and go, “Now I’m at the Big Dramatic Monologue at the end of the second act” and I start to write in a different way. The only solution was to keep my head down and keep doing what I had been doing, which is to stay true to the voice of the dad.

I grew up in the theater and always loved monologues. I’ve always loved an actor just speaking for minutes at a time, uninterrupted. That’s the push and pull here: Someone delivering a speech in a way that they don’t necessarily speak all the time. Also for me, the best writing is a kind of listening. Just letting a thing happen and letting it surprise me — definitely not trying to get the script to go somewhere. But I realized the pressure I was feeling is the same pressure the dad felt. “Oh my God, this kid is asking me if she makes me sad. And holy shit, I need to say some perfect monologue to be able to assure her that’s not the truth!” Writing it, I realized the dad communicating his effort was the most important thing — to show that he actually believed it, not that he had the articulation at his fingertips. He didn’t get seven drafts to get it right.

It’s just trying to service the truth. If you could relisten to a speech that your parents gave you, it’s probably not that great. It’s not, “Oh my dad can rattle off these incredible nuggets of wisdom.” It’s more, “When he tried to soliloquize, I saw in his eyes that he loved me and that he really meant it even if he didn’t have the perfect words for it.” That’s what she really responds to. And I realized that’s what I had to go for. I didn’t want to speak intellectually. It’s a moment that’s meant to be spontaneous and tender and sort of sprung on Dad. If I go into the scene with too many preconceptions, it’s going to squash the thing that makes it feel alive. It’s going to feel overcooked. I had to rebel against my instinct to turn it into some sort of fancy scene.

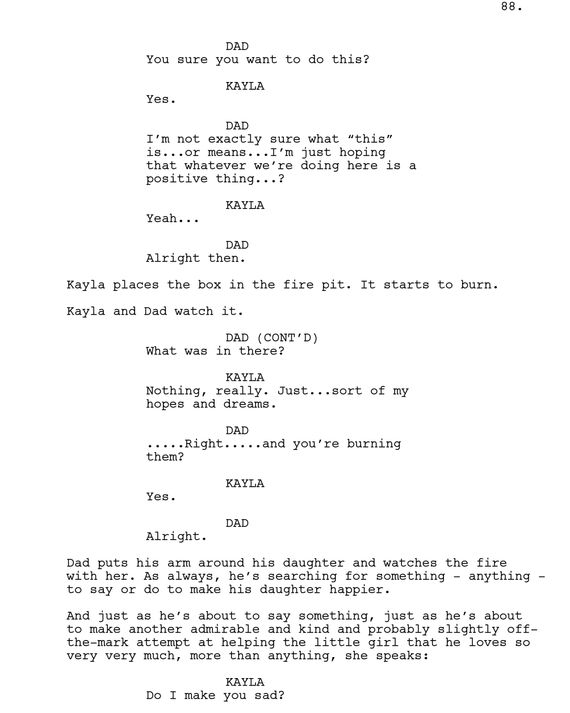

So she burns the box filled with her “hopes and dreams” as a way to get the two of them together, focused on an activity. This definitely comes from me and my parents having emotional talks where, if you can just do something so the attention is distracted, you can justify not having to look at each other in the eye as you say these important things. And I wanted it to feel like, here is some guy who didn’t practice this speech, who didn’t know this night was coming, who never thought a moment like this would come for him. Even though the dad has been giving advice the entire movie, when the advice is finally asked for, he’s like, “How the fuck do I do this again?” For him, it’s so easy to give unwanted advice; it’s so hard to give wanted advice. “She hasn’t asked me for anything in what feels like forever and now she’s saying, ‘Do I make you sad?’”

The way it’s written, it’s the only question that the dad is 100 percent certain of the answer. If she were to ask him about things in her life — How do I deal with people at school? How do I not feel sad? How can I be more cool? How can I get more friends? — that stuff is so hard for a parent to address because you fundamentally don’t know your kids’ life as well as they do.

But with “Do I make you sad?” it’s like he finally feels he has some authority over her experience. “I don’t know what you’re dealing with at school. But I know so deeply that being your parent is the best thing that ever happened to me and will ever happen to me.” She needed to realize she’s good and strong. It’s definitely not about Dad saving her. It’s Dad picking her up and dusting her off and saying, “Keep going. You’ve been going in the right direction the whole time.”

Below read the scripted version of the scene:

Now see how the scene plays out in the finished film: