Audience comments cards from 1969 test screenings of The Wild Bunch didn’t merely express displeasure; they conveyed apoplectic shock. “This movie was TOO DAMNED BLOODY,” read one, proving that all-caps was a thing well before email and Twitter arrived. “No story, just gore, filthy, repulsive = blood, blood, blood!” read another. And this one, reinforcing the fact that not everyone was onboard with the burgeoning New Hollywood: “Whatever happened to the old John Wayne movies?”

Indeed, as detailed in W.K. Stratton’s definitive new book The Wild Bunch: Sam Peckinpah, a Revolution in Hollywood, and the Making of a Legendary Film, this portrait of aging gunfighters fleeing Texas across the Mexican border for one last score was and remains a grimy, fatalistic rebuttal to the Duke’s days of glory. There’s little heroic about Peckinpah’s film. Its frontier is a place of fatalistic tragedy, not whooping triumph. Fifty years later, it still rattles the nerves and floods the senses. Like most films born ahead of their time, The Wild Bunch has only grown in stature over the decades.

That’s largely because the movie isn’t just blood and guts. “Strother Martin once called Peckinpah a ‘dirty psychologist,’” Stratton tells me on the phone from his Austin home, referring to the character actor who plays the most gruesome of the film’s bounty hunters. “When Sam got all those actors down to Mexico, he really did transform them into the characters they became in the movie. There’s a certain verisimilitude there. It doesn’t seem like they’re acting.”

Stratton, whose previous subjects run the gamut from the rodeo circuit to heavyweight boxing champion Floyd Patterson, vividly remembers the day he first saw The Wild Bunch as an adolescent in Guthrie, Oklahoma. “I stepped out of the theater into the night, my heart beating as if I’d just been running hundred-yard sprints,” he writes. “I still feel that way every time I watch The Wild Bunch.”

Stratton’s book is part making-of chronicle, part appreciation, part personal reminiscence. He details the contributions of everyone from Jerry Fielding, a victim of the Hollywood Blacklist who composed The Wild Bunch’s sparse, haunting score, to Chalo González, a Mexican local who saved Peckinpah from a bar fight and became a sort of do-everything fixer on the film. He works in a list of what he considers the best films ever made, including The Rules of the Game, The 400 Blows, and, yes, The Wild Bunch. There’s a certain guilelessness to Stratton’s approach. He’s not a film critic, but a passionate and knowledgeable generalist who knows how to drill deep.

That passion is ultimately what counts in evaluating The Wild Bunch. One of the less outraged among those early comment cards reads: “This picture is burnt into my brain.” The movie has a tactile pungency that borders on the hallucinatory. From the opening sequence, which shows us a gang of smiling, giggling urchins unleashing a swarm of red ants on a writhing scorpion, to the climactic bloodbath, an orgiastic explosion of bloodshed, The Wild Bunch enters the bloodstream like a drug. Released the same year as a number of other Revisionist Westerns, including Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and Tell Them Willie Boy Is Here, and the ultimate urban Western, Midnight Cowboy, it feels more akin to the 1970 acid Western El Topo. That film, too, packed its visceral punch with buckets of blood.

Stratton knows all about the blood — and the exploding squibs that provide it. The graphic violence in much of today’s cinema feels glib and titillating, an over-caffeinated stimulant designed to jack up the teenage boys who account for a massive portion of box-office revenue. By contrast, The Wild Bunch, made at the height of the Vietnam War, wants you to see and feel what bloodshed is really like. Exit wounds were new to cinema, but they reflected the death and destruction Americans were seeing on the news every night.

Two years earlier, Bonnie and Clyde had elicited similarly shocked responses. The Wild Bunch took things further. The opening shootout, which piles up bodies as a temperance union march weaves through a South Texas town, shows where Peckinpah is headed. The action is captured by numerous cameras, shooting at multiple speeds, and nimbly edited to suggest a ballet of carnage. A man is shot off his horse, and we see two children looking on. We cut to the man being dragged by the horse, and back to the children, now slightly alarmed. Another man is shot, exit wound and all, and this time the children shudder. All of this takes place within a few seconds. Women and children aren’t merely onlookers; they also lie dead in the streets. (Throughout the film, the camera has a way of finding small children in close-up. Innocence in The Wild Bunch isn’t long for the world.)

Yet Stratton is here to remind us that there’s a lot more going on than death and destruction. For all that carnage, the film has a core of unexpected tenderness.

“One of the great themes in Peckinpah’s movies is the relationships men have with other men, and the betrayal that sometimes occurs,” Stratton says. “He deals with that explicitly in The Wild Bunch. The violence that drew so much attention when it came out remains significant, but there’s also a psychological aspect.”

Pike Bishop, the surly Bunch leader played by William Holden, is a jilted lover, betrayed by his old partner in crime, Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan). In exchange for clemency from a railroad company he had previously robbed, Deke now leads a gang of redneck bounty hunters in pursuit of the criminals he still longs to ride with. Pike, meanwhile, has a new right hand, the gruffly thoughtful Dutch (Ernest Borgnine, tapping a dark side he rarely got to show onscreen). In one early scene, as Pike and Dutch lie in sleeping bags by a fire, discussing the past and the future, their mutual affection and respect take the tone of pillow talk between husband and wife. All of this runs just beneath the surface of one of the manliest (some would say misogynistic) movies ever made.

“It is a kind of love story, and it fits into a mold of great American literature,” Stratton says. He’s thinking of the relationships at the heart of novels like The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (Huck and Jim) and Moby Dick (Ishmael and Queequeg). This line of interpretation springs from the literary critic Leslie Fiedler, whose essay “Come Back to the Raft Ag’in, Huck Honey!” traced implicit homoerotic bonds in classic novels.

“The Wild Bunch is about men who don’t relate to women very well,” Stratton says. “Whatever kind of affection they have, they can feel really only for each other. There’s no sexual connection, because if they want sex they go hire whores.”

Stratton is also keenly interested in how the film incorporated its Latino cast and crew — a commitment to diversity that adds to the film’s authenticity. Of the 40 actors listed in the film’s end credits, 24 are Latino. (The actor who plays the central Mexican character of Angel was Jamie Sánchez, a Puerto Rican stage actor from New York. Much of the crew resented him, not because he was Puerto Rican but because they thought he put on airs.)

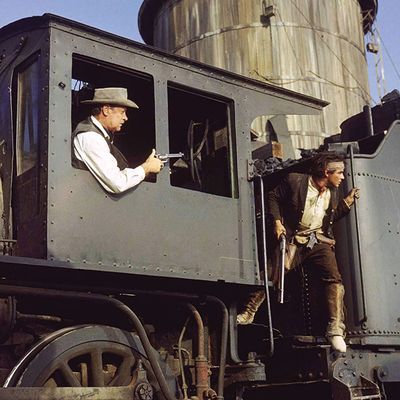

Mexican screen legend Emilio Fernández was also a key figure. His General Mapache is a strongman tyrant at war with Pancho Villa’s revolutionaries. Mapache hires the Bunch to steal some rifles (perhaps the greatest train robbery ever filmed), which doesn’t sit well with Angel, whose village has been pillaged by Mapache’s men. Thus the film adds more layers of betrayal to its festering conflicts — and layers of nuance to parts played by Latinos.

The Wild Bunch remains the high-water mark of Peckinpah’s career, which was marked by angry head-butting with studio executives, alcoholic binges, and, later, mounds of cocaine. (Stratton says Peckinpah’s friend James Coburn suggested coke as a way to counter the effects of the booze. Bad idea.) It’s one of those movies that gets better every time you see it, no matter how many times you see it. The Western never felt quite the same after The Wild Bunch. Paul Schrader once described Touch of Evil as film noir’s epitaph, and the same can be said for The Wild Bunch and the Western. There’s always somewhere new to go in the genre, but the violent intensity, the scale of destruction, and the combination of classical themes and cathartic release of The Wild Bunch haven’t been matched. It’s still the one Western that stares down America’s bloody past and doesn’t blink.