Jimmy Breslin had been assigned to cover a meeting of politicians. This was the early 1960s, and Breslin arrived at the city government building to find reporters from other newspapers sitting in a hallway outside the closed door of the meeting room, dutifully waiting for the gathering to end and to be told what had happened inside. Breslin looked around, disgusted. “That’s no way to live!” he thundered, and then charged back out into the street, in search of a better story to tell.

Breslin’s editor at the New York Herald Tribune, Dick Wald, told that story at Breslin’s funeral in March 2017. Now comes a different kind of celebration. Breslin and Hamill: Deadline Artists, a terrific HBO documentary that premiered earlier this year, explores the lives of Breslin and his most brilliant contemporary, Pete Hamill. The film is overstuffed with colorful anecdotes about the two men. More important, it is suffused with the restless spirit that animated Breslin and Hamill’s writing. For the better part of four decades they roamed the city, talking to regular people and pounding out hundreds of thousands of words on deadline, becoming as noisy and funny and infuriating and integral a part of the city as the subway. What Breslin and Hamill did not do was wait around in hallways to be handed the official version of events.

Deadline Artists manages to add depth to stories that have seemingly been exhaustively told, not least by Breslin and Hamill themselves, beginning with their childhoods in poor, dysfunctional Irish-American families in Queens (Breslin) and Brooklyn (Hamill). One sign of how they would grow into very different personalities and writers: Young Breslin escaped to pool halls, while Hamill headed for the nearby Brooklyn Public Library. Both found their way into newspaper jobs more or less by accident, and quickly showed off their gifts. Breslin’s breakthrough was a hilarious book about the incompetent first year of the Mets, while Hamill turned a job on the nightside desk at the then-liberal New York Post into vivid dispatches mixing crime, blue-collar struggle, and earthy comedy.

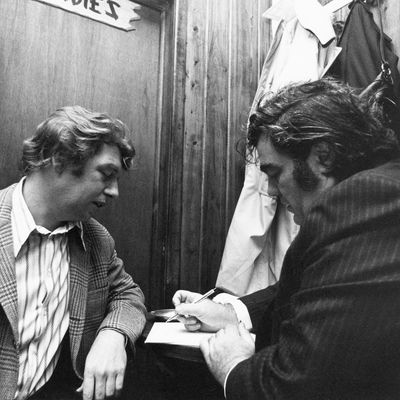

The film recounts how the pair became stars, weaving vintage footage from the ’60s and ’70s with present-day interviews of their collaborators and fans, from Tom Wolfe to Spike Lee, plus, crucially, voice-over readings of snippets of Breslin and Hamill’s work (voiced by Michael Rispoli of The Sopranos and Hamill, respectively). Stories that made them famous get rich backstories. Days after John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Breslin wrote about the man being paid $3.01 an hour to dig the president’s grave in Arlington National Cemetery. Deadline Artists tracks down the gravedigger’s son to talk about Breslin’s legwork and his father’s humility. Five years after JFK’s death, Hamill encouraged his friend Robert F. Kennedy to run for president. In the documentary, he describes typing out a story in Los Angeles on the night his friend the candidate was shot and killed.

Beyond the specific episodes, the film does a remarkable job of portraying an era when newspapers were so important to city life that Breslin could host Saturday Night Live and Hamill could date Jackie Kennedy and Shirley MacLaine — at the same time, in 1977. Their glory days were hardly idyllic, though. The city verged on collapse, and the newspaper business was overwhelmingly white and male. Deadline Artists doesn’t ignore the large flaws of its subjects, either. Breslin infamously spewed racist insults at a Korean-American reporter who dared to challenge the sexist tone of one of his Newsday columns, and Hamill’s alcoholism nearly wrecked his family and his career.

Yet the film is a powerful reminder of core journalistic values. It’s easy to forget that in 1984, when Bernie Goetz shot four black teenagers on a downtown 2 train, Breslin was practically alone in criticizing Goetz as a cowardly vigilante. “We need more of that in our business,” says Jonathan Alter, the veteran journalist who directed the documentary along with Steve McCarthy and John Block. “It’s not just going your own way and finding the fresh angle the way Jimmy did with the gravedigger. It’s being willing to really go against the tide of opinion. And what’s happened as journalism and media has become commoditized, and as ratings and clicks determine everything, is that suddenly journalists need to be popular. There’s a problem with that. We’re protected by the Constitution in order to say things that are not popular, that the government doesn’t like or the public doesn’t like.” That also applies to what Hamill wrote in 1989. He was reacting to a full-page newspaper ad calling for the death penalty in the Central Park Five case, but Hamill nailed Donald Trump both then and now: “Snarling and heartless and fraudulently tough, insisting on the virtue of stupidity, it was the epitome of blind negation. Hate was just another luxury. And Trump stood naked, revealed as the spokesman for that tiny minority of Americans who live well-defended lives. Forget poverty and its causes. Forget the degradation and squalor of millions. Fry them into passivity.”

Deadline Artists arrives as newspapers are dying and local coverage is shriveling. In the film Gloria Steinem tries to sound optimistic, talking about how stories will always get told, even if the format evolves from sitting around campfires to pecking away at Twitter. Indeed, great journalism is everywhere these days, in the work of Breslin and Hamill’s direct heirs, many of whom appear in the film (Michael Daly, Jim Dwyer, Dan Barry, Mike Lupica), as well as indirect descendants including the Washington Post’s David Fahrenthold. And the Sunday magazine published by Breslin’s old employer the New York Herald Tribune morphed into New York Magazine, which is still throwing punches 51 years later. (Hamill has written quite a few gorgeous feature stories for New York himself, including a prescient 1969 piece headlined, “Brooklyn: the Sane Alternative.”)

The most poignant interviews in the film are with its gray and frail subjects. Breslin died nearly two years ago. Hamill, 83, is working on his 14th book. Their written work will be their chief legacy, but, as Deadline Artists makes clear, the inspiration and advice they provided keeps reverberating. One example: In 1980, Hamill hired an assistant, Peter Blauner. Hamill taught Blauner what he calls the three “most important lessons I’ve ever learned about writing”: If you have an experience remotely worth writing about, get the details on paper within 24 hours; always ask the toughest question; read more than you write. Using those tips, Blauner became first an accomplished New York Magazine writer and then an award-winning novelist. And along the way he shared Hamill’s tips with a few kids like me. Deadline Artists should help spread the legend and the lessons of two journalism giants a little further still.

This story has been corrected to show that Pete Hamill was in Los Angeles on the night of Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination.