Lil Wayne’s best breakup song isn’t about a romantic relationship. It’s “I Miss My Dawgs,” the wrenching bit of melodrama from the first Carter album, where each of the three verses is dedicated to one of his friends in the Hot Boys, the sensationally talented Cash Money supergroup in which Wayne cut his teeth, each of whom had left the label on acrimonious terms. Wayne was still there. (As he barks at Turk at the song’s climax: “We thugged, we hung, we ate, we slept / we lived, we died, I stayed, you left.”) Fifteen years and thousands of pages in court filings later, this axes of Tha Carter — those who stayed loyal and those who jumped ship — seems naïve. But “Dawgs” is not overselling the emotional weight of that Hot Boys disintegration; it simply reflects what a crucial period in the lives and careers of its members that the Hot Boys project represents.

The rap music that came out of Louisiana around the turn of the century — especially from Cash Money and its chief rival, the Master P-helmed No Limit — has aged remarkably well. The most visible, canonical records from that time (see: 400 Degreez) are studied and internalized, and the broader, bolder, more unabashedly capitalist ethos we associate with those artists has come into vogue, as a true identity for artists or, just as often, as a knowing wink to audiences nostalgic for something they only half-remember.

But the real, material work put out by many Louisiana rappers of that period is in danger of being lost to the ether due to the fact that it was never cleared for digital streaming platforms. Fortunately, last week, three big dominos from that category toppled onto Spotify: the first two Hot Boys albums, 1997’s Get It How U Live!! and 1999’s Guerrilla Warfare, and B.G.’s ’99 classic Chopper City in the Ghetto, are now available on said platforms. It’s a small step toward digitizing the wealth of rap music that’s brilliant and historically important but remains offline. This trio of LPs represent a key piece of a fascinating and enduring moment in the genre’s history.

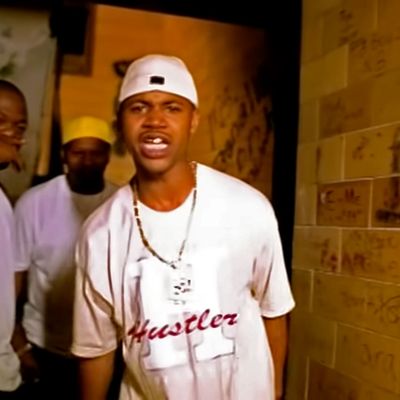

By the time the Hot Boys were formed, Cash Money already had a near monopoly on the imaginations of young rapping talent in New Orleans. Groups like UNLV established what had been conceived as a bounce-music label as a heavyweight in hip-hop. The members were Juvenile, the centerpiece of the label’s second generation, who’d quickly become a phenomenon at house and block parties with a string of unrecorded songs, including and early version of “Back That Azz Up”; Lil Wayne, who had pestered Baby and Slim until they allowed him to become an intern of sorts at the label offices, and whose mother wouldn’t allow him to curse on record; B.G. who, as a 14-year-old, had put out a record with a 12-year-old Wayne, and whose Chopper City had made a significant dent regionally in 1996; and Turk, the last one of the four to set foot in a professional studio, who had once written a playful diss song to B.G. when the two were in middle school. Juvenile was almost a half-decade older than the other three. At the group’s beginning, Wayne and Turk often teamed up and wrote their verses together, in an effort to outshine Juve and B.G., the more established local figures.

Get It How U Live!! was recorded mostly in Houston. Baby took the Boys to watch UGK record, and when Bun B wrote and laid a verse in five minutes, the CEO made sure his protégés understood the same was expected of them. (This recalls the stories — maybe apocryphal, but honestly who knows — of Baby and Slim forcing Cash Money artists to jog around the parking lot of the studio while rapping, to improve their breath control.) The album that resulted from those Houston sessions feels exploratory, and intriguingly small, like the razor teeth are just growing in. “I’m Com’n” — which features a Bun B verse, presumably cooked up on the spot — is an early window into the group’s pop potential. Aside from producer Mannie Fresh, one key element the Hot Boys had going for them was a collection of four distinct, once-in-a-lifetime voices, and hearing Juve and a still-embryonic Wayne play off one another is a thrill.

By contrast, Guerrilla Warfare is fuller and meaner, blunt and punishing. When it was released, Juvenile was a bona fide star, and the label was at the peak of its powers; Wayne had figured out how to channel his exuberance into something that felt like controlled mania, frenzied but foreboding. There’s more from Turk, who was finally in his element in the Cash Money factory setting. (This one was written and recorded in Miami in a single week.) See especially “Tuesday & Thursday,” a perpetual motion machine full of dread.

Despite Turk’s raw, obvious talent, there is not a clear or canonical masterpiece from his catalogue. B.G. is the opposite case — it would be hard to argue that his discography mis- or under-represents his ability, but he’s been pushed from the front of rap fans’ minds in a way Juvenile has not. Chopper City in the Ghetto, his first album after Cash Money signed a deal with Universal, is a sly masterwork, with less fat than its era, length, and label would suggest. B.G. has always been an inimitable vocalist (a friend of mine recently texted me, apropos of nothing: “B.G. sounds like what I think an iguana would sound like”), and CCITG hears him in superb control, from the obvious — “Bling Bling” — to more personal fare like “Uptown My Home.” The album does an excellent job of marrying the maximalist veins Mannie Fresh was tapping into at the time with Cash Money’s old playfulness.

If you have even a cursory familiarity with Cash Money’s history, you know none of this would last. Sending, and then confirming with the help of attorneys that his contract was all types of fucked up, Juve left the label in 2001; B.G. and Turk followed shortly thereafter. It would turn out, tragically, that the money they may have left on the table was far from the worst thing on the horizon. Juvenile used some of his advance money to buy a home that was destroyed in Katrina — and in 2008, his 4-year-old daughter and her mother were murdered in their home. Both B.G. and Turk were dogged by serious problems with hard drugs, and each spent long periods incarcerated. Turk served 9 years of a 14-year sentence stemming from the 2004 shooting of a police officer in Memphis. He was released in 2012. Just months before Turk’s release, B.G. received his own 14-year sentence: to a federal prison for gun possession and witness tampering.

Two decades after the Universal deal, the aesthetic hallmarks of that Cash Money era are perhaps more popular than ever — and certainly better respected by critics, and by the rap fans above the Mason-Dixon Line who might have sneered in real time. Kids born after 9/11 swipe Pen & Pixel’s visual vocabulary for their own mixtape covers; “Ha” is reimagined by young rappers from coast to coast. One of the loosest and most endearing off-wax glimpses into the personality of Kendrick Lamar, whose public appearances usually feel tightly rehearsed, was his re-creation of the “I Need a Hot Girl” video. And while there is, at the present, more compelling rap coming out of Baton Rouge than New Orleans, that former city’s biggest rising star, YoungBoy Never Broke Again, alludes to the Cash Money legacy as a kind of shorthand. The long-overdue issuing of these three albums to streaming services ensures, at least for the moment, that the real, material work those artists made is accessible, rather than just the abstracted notion of their style.

But back to Tha Carter. Immediately after “I Miss My Dawgs” comes “We Don’t,” where Wayne trades verses with Baby. In 2004 it was de rigueur; with hindsight, it’s deflating to hear Wayne sink back into the machine. But it’s easy to bury that feeling and focus instead on how simply, exhilaratingly good Wayne is at rapping on that album. There’s an understandable misconception that Tha Carter marked the end of Wayne’s apprenticeship, the last moment before he struck out on his own. It was the last album (aside from one more solo effort) that Mannie Fresh produced in its entirety for Cash Money; it was the last Wayne album before Katrina, and before he moved full-time to Miami. It’s the last album of his that sounds like a more or less unadulterated extension of what was happening in rap and bounce music in New Orleans in the ’90s. The myth, it seems, would fit.

In truth, Wayne had spent the year-and-a-half leading up to Tha Carter rapping over industry beats from far-flung regions and in styles that had previously been foreign to him. The album was a return to his old neighborhood, back to the roots and back to where he came from. But when he came back, everybody else was gone.